by Milo Hsieh

語言:

English

Photo Credit: Huang Rong-zan

AS TAIWAN TOOK a break last month to remember the incidents of February 28th, 1947, 228 and transitional justice once again came up as a topic of debate. On Thursday, March 1st, a debate was held at the TECRO Cultural Center in the DC Metropolitan Area by several Taiwanese organizations with the sponsorship of Taiwan’s de-facto embassy in the US, the Taipei Economic and Cultural Representative Office.

The topic was “whether continuing to identify responsibilities for the 228 incident yields more benefit than harm or vice versa” (繼續追究二二八事件/責任對台灣利大於弊/弊大於利). Four Taiwanese college/graduate students split into two teams to present arguments. The discussion was set up in the form of a debate, but debaters drew straws to decide on which side they represented, rather than representing their own personal position.

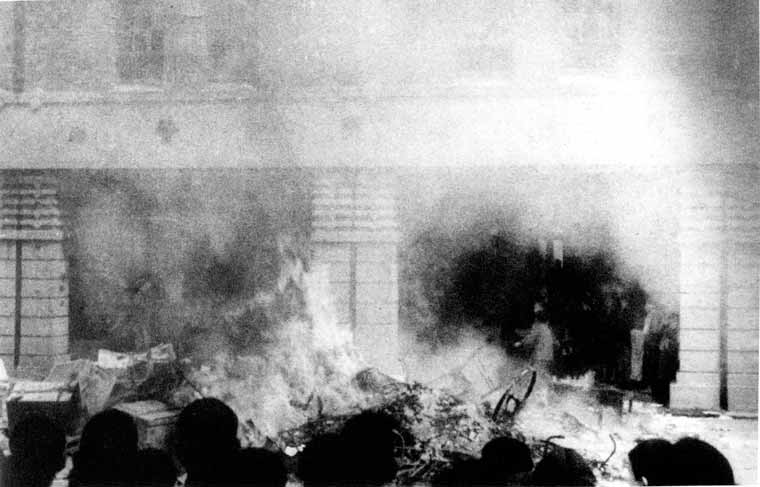

Demonstration in front of the Tobacco Monopoly Bureau in Taipei. Photo credit: Historic photo

Demonstration in front of the Tobacco Monopoly Bureau in Taipei. Photo credit: Historic photo

The pro-side argued that despite the number of years passed since 1947, Taiwan ought to continue establishing transitional justice for the victims of 228 and their family members. Despite potential retraumatization to the victims, the pro-side argued that it would serve the divided Taiwanese society by bringing out the truth as a platform for reconciliation.

In response, the against-side argues that traumatization caused by digging up the past would outweigh potential benefit granted. The political environment and the quality of the media in Taiwan, they claim, is unfortunately unfit for such a civil discussion. The distortion of truths and the inability to truly see objectively the past prevents such discussion.

Also noted is the animosity between the waishengren (外省人), commonly seen as the perpetrators, and the benshengren (本省人), a group seen as victims of 228. The term” Waishengren” by literal definition refers to those coming from other provinces in China, but more commonly they refer to the KMT-affiliated Chinese elites who retreated with Chiang Kai-shek in 1949. “Benshenren” refers to the Han people who resided in Taiwan before Chiang’s retreat, but colloquially members of this identity groups refer to themselves as “Taiwanese” (台灣人). It is important to note that the etymology of these formalized terms assumes Taiwan to be a province or “sheng” (省) of China.

The debate closed with acknowledgements by both sides of the difficulty of setting up a proper civil discourse on 228. “Whether the real truth will allow Taiwan to reconcile” is at the center of the discussion, and this “reconciliation process” is compared to models such as the post-WWII Germany.

Indeed, there has been much discussion over whether the Taiwanese society is even capable of reconciling. The high level of polarization between the waishengren and benshengren presents a challenge, with a high level of identity politics at play. Benshengren who perceive themselves as victims may prefer active efforts to seek the truth in conflict with the interest of waishengren, who mostly fear retaliation, witch-hunting, and further polarization in Taiwan. That being said, ethnic divisions among young people are no longer so clear, with intermarriages and shifts in political identification among third-generation waishengren.

Musha, where the Musha Incident broke out, during the Japanese colonial period. Photo credit: Historic photo

Musha, where the Musha Incident broke out, during the Japanese colonial period. Photo credit: Historic photo

The post-debate Q and A session highlighted this exact difficulty. One audience member poses the Musha Incident (霧社事件) was similar to the 228 Incident, and asked whether Taiwan ought to similarly seek truths as it is currently doing for 228. After the question was asked, several members of the audience booed him, and a loud unorganized exchange between the speaker and the audience followed. The moderator had to step in to maintain order and to set speaking time at two minutes per question.

The audience members who disrupted the speaker most likely felt insulted when the 228 incident, which killed mostly Han Taiwanese, was compared to the Wushe Incident, which killed mostly indigenous Taiwanese. There was also a much higher sense of resentment towards the KMT regime that took back Taiwan after 1945, and ruled through authoritarianism after 1949, compared to the Japanese colonizers that ruled Taiwan from 1895 to 1949. On the posters presenting information about 228 incident at the TECRO Cultural Center, it is said that the view of Han benshengren Taiwanese towards the Japanese was that they had ruled Taiwan in a more orderly fashion than waishengren, who were said to be corrupt and incompetent after they took the Island back in 1948.

Identity politics presents itself as a challenge to confronting and resolving 228. The issue, however, is at times also a feedback loop. The waishengren-benshengren conflict feeds into polarization and unwillingness to confront 228 truths by some Mainlanders, yet at the same time, this polarization and unwillingness prevents reconciliation between the two sub-ethnic groups. While these identity groups have been highly polarizing amongst the older generations, there is a lack of these distinctions amongst younger people, likely given democratization and introductions of other identity groups, such as foreigner Taiwanese, Southeast Asian new immigrants, etc.

Several audience member also brought up memories of lost family members due to 228, as well as cases of false accusation/arbitrary arrests that led to the death or shaming of both waishengren and benshengren. As they present their anecdotes and family history, many could not hold back tears as they call upon more efforts to find truths about 228.

Despite the value in listening to oral narratives of the audience, which shone lights to just exactly how traumatic these experiences could still be after more than 70 years has passed, the medium of their narratives—in anecdotal forms—shows how discussions on the topic is difficult.

228 Museum. Photo credit: WikiCommons/CC

228 Museum. Photo credit: WikiCommons/CC

Given the tight control on the media by the KMT regime during authoritarian years, these oral narratives has been passed down the generations and are told mostly from secondhand accounts. Most of those imprisoned or executed without due process never lived to tell their tales, so today these oral narratives exist in the form of memories and oral accounts of relatives to tell their last words. History as taught to the youth of Taiwan has for a long time omit this part of Taiwan’s history, since the KMT media control ensured that any potential challenges to the regime’s power.

This creates a problem for looking at 228 from a historical perspective. Despite the clear knowledge that it had occurred it traumatized so large a section of Taiwan’s society, what exactly occurred is muddled by competing historical claims and the vast volume of oral narratives. This has obscured progress to find those responsible. Formal history for a long time was dictated by what the KMT wanted the public to learn, rather than what it actually was.

Now in 2019, despite the vibrancy of democracy Taiwan, discussing 228 is still hard because of its authoritarian history. There is now a knowledge gap that fails to account for the trauma of many Taiwanese. The need to consult oral narrative to supplement formal history to construct the historical truth can easily fall into a slippery slope where different identity group in Taiwan selectively pick “facts” to construct claims that do not represent the historical reality.

Though the formal history of 228 remains hard to establish, modern technology, a developed media, and the widespread use of the Internet have now enabled methods of discussions unavailable in the past. The debaters arguing in favor of finding truths about 228 proposed that the media and the internet ought to serve as a forum of discourse for Taiwan, yet the question remains over its competency and appropriateness as a forum.

It is often acknowledged that Taiwanese media is frequently of poor quality and can often create discussions that polarizes than reconciles, since monetary gain – view counts and revenue – rather than priority placed on values such as social reconciliation, incentivizes the way shows and channels frame discussions and news. Conservative media, moreover, frequently attempts to downplay the importance of 228 and do not attempt to present the truth at all.

Yidingmu Police Station on February 28th, 1947. Photo credit: Historic photo

Yidingmu Police Station on February 28th, 1947. Photo credit: Historic photo

Though the Internet, on the other hand, may seem like a freer forum of discussion, the structure of social media similarly locks people into echo chambers. Facebook groups and Line groups in Taiwan are examples where groups of people self-select channels of information and form echo chambers. Combined with a press that is perceived as untrustworthy, many worry that more conversation on it will simply polarize Taiwan even more.

Despite the long path which continues to be needed for the development of civil discourse in Taiwan—the debate itself being an example of this process—it should also be evident that Taiwan still has much room for improvement. Taiwan’s lack of experience with democratic values is a major reason why many of the issues it is facing exist today. Both the media and the public of Taiwan ought to be better equipped in informational literacy and media professionalism, which would facilitate a better discussion from groups that understand rather than rejects the arguments presented by the other side.

Until the Taiwanese public is able to better understand and practice civil discourse under a democratic system, discussions of 228 as a historical trauma will continue to be difficult and blocked by these structural issues.