by William Langley

語言:

English

Photo Credit: Robert Mandel/WikiCommons/CC

AN IMPASSIONED, at times desperate, public debate, the imminent threat of irrelevancy, and existential angst induced by the looming presence of a larger neighbour. With President Tsai Ing-wen’s Taiwan seemingly on a collision course with mainland China, and with Theresa May’s latest frustrated attempts to extricate the UK from the EU, all are increasingly pervasive features of the political climates on the two small islands at either end of Eurasia.

In the UK and in Taiwan, the relationship between the island and mainland neighbour is both historic and contemporary. In many ways, these relationships are similar.

Firstly, the modern-day majority populations of both Taiwan and the UK are largely the result of historic immigration from the mainland. During the wars of the 20th century, both islands saw an increase in this migration, receiving mainland migrants who would play a major role in the shape of their host countries’ modern fates.

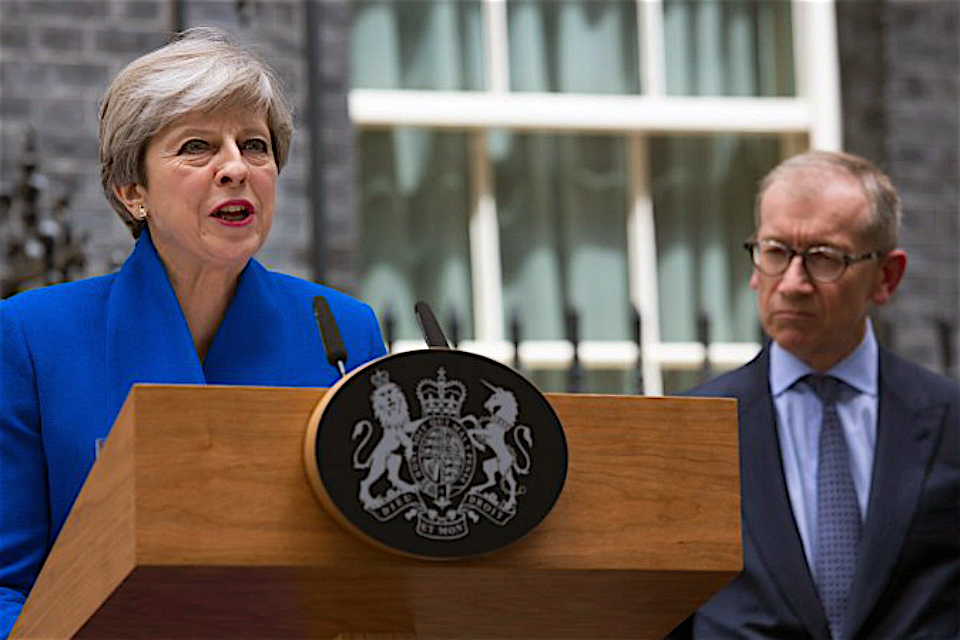

UK prime minister Theresa May (left). Photo credit: HM Government/WikiCommons/CC

UK prime minister Theresa May (left). Photo credit: HM Government/WikiCommons/CC

What’s more, both island-nations are separated from the landmasses that represent both their closest cultural relatives and their bitterest rivals by just a narrow strip of water: at their widest, the Taiwan Strait is just 220 kilometers and the British Channel, 240 kilometers (or 150 miles, depending on which side of it you fall on). And yet, on both islands, one finds a people with a sense of distinctness, born of the separation from the history, politics, and affairs of the neighbouring continents, afforded to them by those narrow strips of water.

In the present day, Europe and China remain significant to their island neighbours, representing their major trading partners. Interestingly, both the UK and Taiwan have also found themselves, either historically (in the case of the former) or currently (in the case of the latter), caught between the pull of their immediate neighbours and that of the United States, which remains the second largest trading partner of both countries.

It is in terms of these modern-day relations where the two islands share the most in common.

In Taiwan, modern-day cross-strait relations began after the Chinese civil war, when the KMT fled to Taiwan and declared Taipei as the new seat of government for the Republic of China. From then on, the island’s relationship with the mainland has been a prominent, if not defining, feature of its political debate. This deepened as the island democratized in the 1980s and 90s, when a political dichotomy emerged between the KMT ‘blues’, who uphold the legitimacy of Taiwan’s Chinese identity, and the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) ‘greens’, who call for greater independence from the mainland. Since Tsai Ing-wen of the DPP was elected as president in 2016, relations with mainland China have soured, with the Office for Taiwan affairs branding President Tsai a “separatist”, and Beijing threatening the use of force to bring the island under his control.

In the UK, the relationship with Europe has been a constant source of disagreement for over forty years. The UK joined the European Economic Community, the predecessor to the European Union (EU), in 1973, nearly twenty years after it was founded. Just two years later, it held a referendum on whether to continue its membership. The UK again showed its euro-scepticism in the 1990s, as it refused to join the other EU member states in adopting the Euro as a unified single currency.

Photo credit: Avij/WikiCommons/CC

Photo credit: Avij/WikiCommons/CC

Since then, political and public debates over the UK’s role in the EU have grown more polarised and concerns over immigration, sovereignty and subsidies came to a head in the UK’s 2016 EU referendum, in which 51.2% voted in favour of leaving the EU. The aftermath of the referendum revealed deep divides within British society and politics, between the cities and the countryside, between Scotland and England and between ‘Remainers’ and ‘Brexiteers’. This rift has broken through party lines, and in recent months has consumed all political debate, turning the UK’s once-thriving democracy into a bitter, bi-partisan struggle with no clear end in sight.

Thus, most importantly, both Taiwan and the UK are currently facing crises as to how to define their future relationship with their neighbours. Which leads us to the developments of the past couple of months, where the two nations’ responses each dilemma begin to differ.

In the face of such a crisis, Taiwan has exhibited confidence, level-headedness, and democratic maturity.

In local elections last November, for instance, despite the fact that only 26.1% of Taiwanese backed the idea of further integration with the mainland (long seen as a key KMT principal), the island voted for the KMT in 15 of 21 mayoral and magisterial seats. Particularly shocking was the DPP’s humiliating defeat in their former stronghold of Kaohsiung.

The KMT’s victory owed to their focus on ‘bread and butter’ issues, such as creating jobs and economic development, rather than on the basis of the traditional polarised pro-PRC/pro-independence dichotomy. As Josie, a Taiwanese designer currently living in Guangzhou, told me, “Nowadays, in election campaigns, no one has the ‘right’ answer to the issue of cross-strait relations, so it falls lower down the list of priorities. Since the 50s and 60s, the economy has really slowed, so economic issues become more important.”

KMT election rally on November 23rd, 2018. Photo credit: Brian Hioe

KMT election rally on November 23rd, 2018. Photo credit: Brian Hioe

In other words, the KMT likely won in spite of their pro-Beijing stance, rather than because of it. The DPP, on the other hand, were defeated when their approach, which focused on ‘the China issue’ and relied on the traditional identity politics of previous decades, proved insufficient. The upshot is that, in Taiwan, voters’ viewpoints no longer come second to their identities and while there remains a major blue-green division within Taiwanese politics, the two parties have begun to compete on other issues

Moreover, as Josie tells me, when political disputes persist, then tend not to divide people as they used to, “My dad is a pan-green, but my mother is pan-blue. Where my dad feels that we’re Taiwanese [rather than Chinese], my mom thinks we should acknowledge China as our cultural heritage… but actually, we all get along just fine.” When I suggested that in the UK, Brexiteers and Remainers struggle to share a room with one another, let alone a household, or a marriage, she laughed, “ten, fifteen years ago Taiwan was like that, but this issue has been around for so long, it’s just not like that anymore.

Finally, despite their differences, the Taiwanese appear decisive and united on the most pressing issues. In the wake of the pro-Beijing KMT’s election victory, when Xi took to the rostrum to re-affirm his commitment to his historic ‘mission’ of reunification, Taiwanese politicians from across the spectrum united to denounce his calls for ‘One Country, Two Systems’ (the system that the PRC employs in Hong Kong, which many feel has seen the island’s autonomy and freedom greatly eroded). DPP President Tsai Ing-wen re-iterated her rejection of the so-called ‘1992 consensus’ and the need for China to respect Taiwan’s independence and democracy, whilst even KMT politicians, such as Chiang Wan-an, a great-grandson of Chiang Kai-shek, also rallied against Xi’s suggestion, reminding the PRC, “Taiwan is not Hong Kong. Most Taiwanese can’t accept Beijing’s ‘one country, two systems’ proposition.”

Moreover, according to polls, support for Taiwanese independence rose by 12% in the month of January alone, indicating that the public, too, is clear in their response to the existential issues they face.

Of course, Taiwan’s democracy is not perfect. Alongside his ‘bread-and-butter’ appeal, Han Kuo-yu, the new mayor of Kaohsiung, was also elected for some pretty blatant populism, and has already substantially increased the city’s debt and admitted that ten of his twelve ambitious election policies are unlikely to be met. There were also widespread claims of electoral interference orchestrated by Beijing, Chinese state-sponsored dissemination of false news and evidence that the issue of cross-strait relations still holds some weight in voters’ decision making.

Kaohsiung mayor Han Kuo-yu. Photo credit: Han Kuo-yu/Facebook

Kaohsiung mayor Han Kuo-yu. Photo credit: Han Kuo-yu/Facebook

Moreover, a major, unanswered question for Taiwan remains: what can actually be done to bring about the will of its people? With China more economically prosperous, technologically advanced and militarily powerful than ever before, it has a variety of instruments at its disposal to submit Taiwan to its will. And with the level of political unity and determination seen under Xi Jinping, it seems inevitable that it will seek to do so.

Nonetheless, the UK public could learn a lot from the level-headedness of the Taiwanese case. Indeed, despite the existence of huge existential threat in the form of Xi Jinping’s PRC, the public continues to hold politicians accountable, demanding from them solutions to real issues, rather than just ideological stances.

The UK, however, is moving in the opposite direction. As the Brexit debacle rumbles aimlessly onwards, traditional political debate has dissolved entirely and politicians are gradually discarding the ideas that once marked them apart. They no longer debate in terms of economic left and right, libertarianism or conservatism or even Labour or Conservative, rather they take to their milk boxes to preach, Europe or Brexit, leave or remain, ‘us’ or ‘them’. This month alone, nine Labour MPs quit their party because of their frustration at the leader’s refusal to back another referendum. Eight of them have joined with three ex-Conservative MPs, with whom they share little ideological common ground, to form an independent parliamentary group united only by mutual opposition to Brexit.

When Anna Soubry, one the most prominent MPs in the group, explained in an interview, “We don’t have any policy, we’re not a political party”, she flatly underlined the way politicians currently view the pyramid of their political priorities: Brexit first, Brexit later. As the country renounces debate for bi-partisan identity-posturing, the politics of daily life and day-to-day issues are increasingly side-lined.

Not only does this deepen the rifts that exist in the country, but it also serves as a smokescreen, helpfully obscuring the bleak reality the country now faces. By focusing our political energies on bi-partisan feuding, we’re able to drown out the terrifying noises of the options now presented to us.

Formosa Alliance rally on October 20th, 2018. Photo credit: Brian Hioe

Formosa Alliance rally on October 20th, 2018. Photo credit: Brian Hioe

Just as the most die-hard remainers would be nervous to shoulder responsibility for calling a second referendum, the most vocal Brexiteers must surely fear a no-deal scenario, which would see the UK crash out of all treaties and trade agreements it built over the last 40 years with no interim arrangements or future plan, and could have major consequences for everything from medical imports and food supplies to national borders and citizenship rights. So instead, they resort to impassioned arguing, hoping to avoid facing up to reality: that, for instance, it’s impossible to avoid a hard border in Ireland without enforcing a so-called ‘backstop’, or that a second EU referendum would leave the country even more embittered than it already is, that, no matter what the outcome, we are facing an indefinite period of real hardship.

The prospect of a Taiwanese referendum on its future relationship with China this year, called for by the pro-independence Formosa Alliance, then, serves to underline an important difference between the political situations of each country. Where the consequences of a pro-Beijing result to such a referendum may be predictable – undermining the legitimacy of the pan-Green movement and essentially giving Beijing a remit to gradually extend its economic and political control over the island – an anti-China result, which is the most likely outcome, would re-iterate Taiwan’s reluctance to integrate with the mainland but do nothing to answer the underlying question of how, in practice, Taiwan could hope to resist China.

Meanwhile, also in practice, the choices facing the UK in the wake of its referendum are clear, if uninviting. Ultimately, the UK can choose one of three options: to leave the EU without a deal, to hold a second referendum or to delay exit from the EU in the hope of a re-negotiating a better outcome.

Whilst the ultimate consequences of these choices are unclear, when looking at the UK through the prism of Taiwan, the country is in a fortuitous position: we are facing an EU that wants a good deal, an EU set up to maintain peace and an EU that does not, as China does, threaten the use of military force.

Photo credit: Kenneth Allen/WikiCommons/CC

Photo credit: Kenneth Allen/WikiCommons/CC

In choosing between these options, it is, of course, crucial to first answer the underlying question of how the UK envisions its relationship with the EU. This, no doubt, is one of the biggest political questions faced by Britain in the last fifty years. And yet, to pursue this issue only at the cost of all others is divisive and undemocratic. In November, the Taiwanese electorate reminded the DPP that politicians are no longer elected on the basis of single issues. The UK would be best to heed this lesson: whilst the Brexit debate consumes all, jobs are made and lost, families go hungry and the homeless number in the hundreds of thousands. Perhaps, if treated as a problem that needs solving, rather than as an age-defining question of identity, compromise can be struck, we can find some common ground and we can proceed with rationally solving the various, deeply troubling issues that Brexit creates.