by Brian Hioe

語言:

English

Photo Credit: Taipei Arts Festival/Facebook

As part of New Bloom’s current collaboration with the Taipei Arts Festival’s ‘Think Bar,’ we will be keeping an ongoing journal of what goes on during the arts festival. This page will be updated regularly through the course of the ‘Think Bar.’

August 9th

AFTER AN opening press conference, the first event of the 2018 Taipei Arts Festival was a short rehearsal of Provisional Alliance, a performance piece with different members of society—drawn from civil society groups, activists, artists, and others—negotiating different demands as decided upon by a moderator. The performance began in a recitational manner with participants chanting a sort of oath and the subsequent proceedings as decided by a speaker, perhaps mimicking the ceremonial, ritual-like processes which develop in the course of governmentality. However, this was not the full performance, just a brief segment of it.

This perhaps proved a nice segue into the first panel event of the festival, with a talk by Inza Lim on the artists’ blacklist in South Korea under the Park administration, and resistance by members of the South Korean theater community to the blacklist—which can be seen as a protest movement against governmentality run amok, unmoored from any form of accountability or process.

Opening press conference for the Taipei Arts Festival. Photo credit: Brian Hioe

Opening press conference for the Taipei Arts Festival. Photo credit: Brian Hioe

As another recently post-authoritarian country, South Korea of course draws sharp parallels to Taiwan. The movement to oust Park in South Korea could be directly seen as comparable to the Sunflower Movement in Taiwan, insofar as this involved protest against resurgent authoritarian actors with ties to the old authoritarian regime, such as Ma Ying-Jeou and the KMT or Park Geun-hye—the daughter of former dictator Park Chung-hee and leader of the Saenuri Party.

As described by Lim, it was a gradual process of artists speculating about the existence of the blacklist after discovering that they seemed to be blocked from government funding, increasingly confirmed as government raids began to take place on art events in the name of ensuring that works were not disruptive of public morality. Eventually, reporting made it clear that there was such a blacklist.

Artists formed a protest occupation in the Seoul city center where they held performances in demonstration, in cooperation with community leaders, or even the mothers of victims of the Sewol Ferry disaster. Yet the public at large originally thought that this was a matter confined to the artistic community before issues exploded into the public sphere in such a manner as to lead to the massive protests which eventually led to Park’s impeachment.

Rehearsal of Provisional Alliance. Photo credit: Brian Hioe

Rehearsal of Provisional Alliance. Photo credit: Brian Hioe

One notes comparisons to demonstrations led by artists in Taiwan before the Sunflower Movement, such as the “4-5-6 Movement”, which was led not by theater performers and producers, but by film directors. These similarly featured musical performances, theater, and performance. Nevertheless, it does seem that in the movement to oust Park, there was a greater degree of participation by South Korean artists in and through their identity as artists. This use of the identity of “artist” as a primary entry point into social movement was not the case with Taiwanese artists, who usually subsumed themselves into the movement writ large, as seen in that artists did not maintain their own separate occupation.

Either way, the South Korean case seems more severe than that of Taiwan, seeing as recent revelations made it clear that a military coup was planned by elements supportive of the Park administration. Though there were such fears in Taiwan, this seemed much more unlikely during the Sunflower Movement—although these fears were much more credible during earlier stages of the Taiwanese democracy movement, such as during the 1990 Wild Lily Movement.

Eisa Jocson’s performances that night, Macho Dancer and Corpography, would be meditations on the relation of the body and political economy. Macho Dancer involved Jocson’s recreation of the macho dance, a form of seductive dancing by young men in the Philippines directed and women and other men—except gender troubled through Jocson’s gender inversion and strategic use of androgyny.

Talk on the artist’s blacklist in South Korea. Photo credit: Brian Hioe

Talk on the artist’s blacklist in South Korea. Photo credit: Brian Hioe

What was particularly striking about the performance was Jocson’s registering viscerally the powerful physical-affective labor of the macho dance, which regular performances of the macho dance may seek to efface rather than make visible. Camp was balanced perfectly with a great deal of physical, muscular tension—more sensuous in terms of its strong physicality and presence than sensual per se, one might say.

This would seem to be a theme echoing through Jocson’s work, in which the artist uses her own body as a text for racialized labor, as in pole dancing, the macho dance, Japanese hostesses or Disney princesses. In this, Jocson is able to successfully metamorphose into a number of distinct roles in polymorphous fashion, while revealing the racialized, physical undercurrents behind these different forms of dance. As forms of dance, these dances are always to come off as naturalistic motion, but they never are; that they are a form of improvisational acting as much as they are dance and undergirding all this is that these dances are a form of labor bound up with the transnational economy of desire between white bodies or East Asian bodies and Southeast Asian bodies.

Performance by Jocson. Photo credit: Taipei Arts Festival/Facebook

Performance by Jocson. Photo credit: Taipei Arts Festival/Facebook

Perhaps the question, then, is can the living commodity speak through dance?

August 10th

ONLY MANAGED to make it to one event today, unfortunately missing out on Moderation by Miki To, from Macau, which was an artist’s talk on Corponomy with not only Eisa, but also Tadashi Uchino and Pecha Lo. I missed out on the former due to going to the wrong location, somehow.

The talk focused on Jocson’s work in line with contextual and historical developments. Uchino raised that there is a sense of affirmation to her work with regards to the subjects she pursued, rather than simply denying them or conducting ideological critique. Jocson herself emphasized that she tried to keep her work simple, but that material constraints of funding were also highly determinant of the end results, such as that she has to keep in shape to perform Macho Dancer, and so has to constantly work out to maintain her body even when the work is not being performed.

Artist’s talk by Jocson. Photo credit: Brian Hioe

Artist’s talk by Jocson. Photo credit: Brian Hioe

Audience members raised questions regarding the situatedness of Jocson’s work in her own life or practice. Jocson stated in response to a query about whether her work could be performed by someone else that she did not think that would be appropriate, seeing as her work originates in her own history.

Likewise, with regards to questions about whether the macho dancers Jocson studied had attended her performances or whether she had performed macho dance at regular macho dance venues, she stated that Macho Dancer is positioned as part of contemporary dance, and she would view it as an act of violence to try to force that work back into the sphere of macho dance—on the other hand, although there have been cases of macho dancers attending her work, and she hoped to perform at a macho dance club once, if she did such a work, it would have to be collaborative with the space.

As for me, I was most interested in how Jocson’s work involves a great deal of research in order to approach an object of study, but then one self-transforms into that object of study to some extent—a sort of rupturing of the strict boundary between subject and object that one sees, for example, in anthropology.

August 11th

THE TALK BY Florian Malzacher and subsequent panel with Yi Wei-Keng, Po-Wei Wang, wen yau, and Tang Fu Kuen, focused on political theater, although also discussing performance art. Malzacher outlined what he saw as two previous models for political theater, one which sought to present political issues to an audience, with performers taking on roles vis-a-vis such issues, as well as forms of political theater which sought to disrupt the purely representational through, for example, not having a clear line between audience and performer, or which seeks to be keenly aware of the means by which theater is not just reproducing a text, but also producing an event in itself—something Malzacher connected to the ethos of the Taipei Arts Festival itself. Perhaps at stake with such concerns, then, were questions regarding mimesis and attempts to break out of a purely mimetic mode of theater.

Drawing from Brecht, Malzacher sought to point to new directions that he saw for theater with bringing it back into contact with direct political practice, rather than simply becoming more and more abstracted because it is not in line with practice. Examples that Malzacher drew from were Occupy Wall Street, such as the human mic, or Reverend Billy and the Church of Stop Shopping, and other common features of theater in occupation-style movements in past years. Malzacher suggested that forms of direct action in activism as being very similar in ethos to theater. Malzacher subsequently raised the notion of theater as agonistic assembly to point to the conception of a space in allowing for different contesting hegemonies to co-exist rather than to strive towards some Platonic ideal of consensus.

Talk by Malzacher. Photo credit: Brian Hioe

Talk by Malzacher. Photo credit: Brian Hioe

Panelists raised issues such as theater as potentially being too much of a one-way discourse, the overly politicized nature of contemporary society and theater as potentially being a space for refuge from that society, theater as a space for play, or online xiangmin PTT activism as a space for theater.

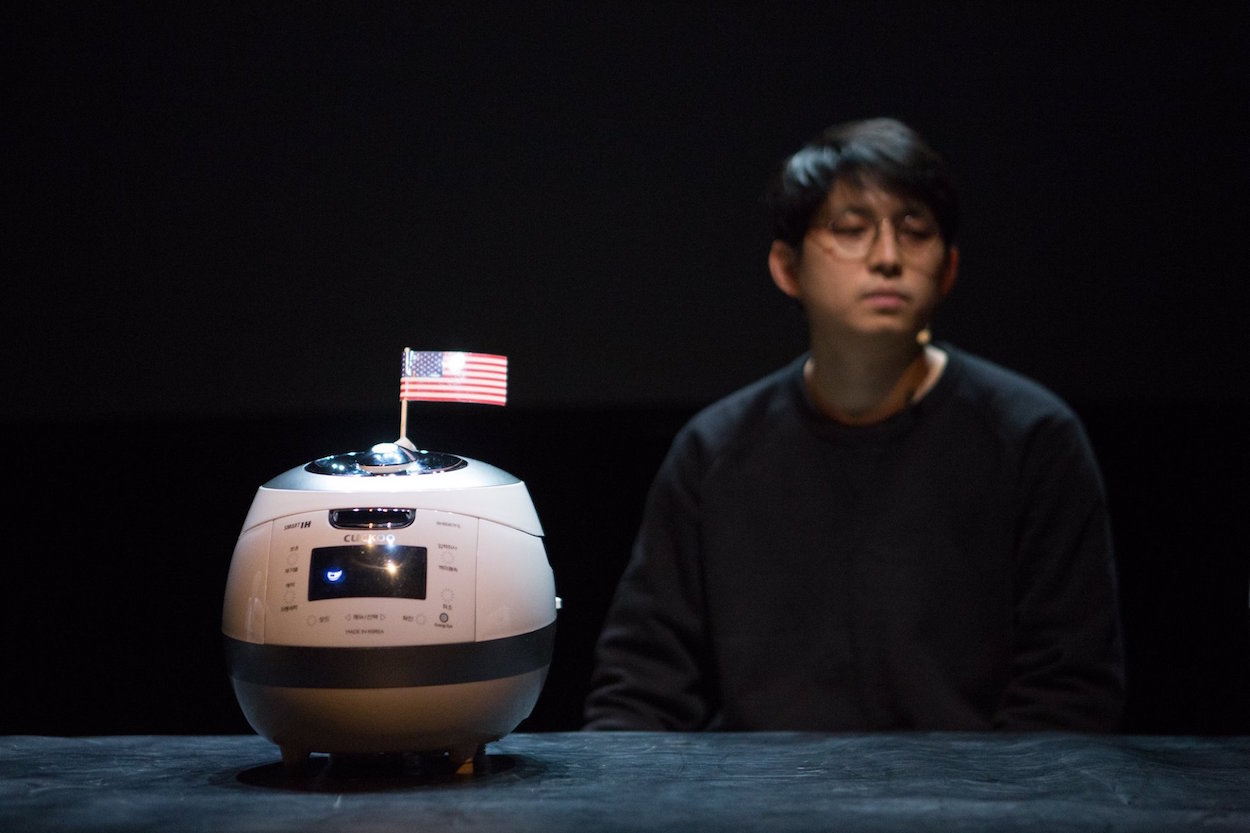

At night, I watched a performance of Jaha Koo’s Cuckoo, featuring three talking electronic rice cookers who begin the performance by talking amongst themselves but later act as intermediaries for Koo when he later comes onto the stage and begins to act as the narrator of the performance. Cuckoo proved a meditation on the effects of neoliberalism forced onto South Korea by America through the 1997 IMF loan of 55 billion USD to South Korea in return for the opening up, control of, and restructuring of South Korea’s economy.

As a result of the effects of actions by faraway American policymakers, Koo experienced events such as the death of a friend, friends moving away, and his eventually leaving South Korea for Europe took the form of a sort of exile. Koo’s work, then, related macro-level history to micro-level history, interweaving larger national and global events with his personal history. The rice cooker, then, would be a medium through which this is accomplished. Accompanied by video art and music composed by Koo, the work is at once comic but also heartfelt.

Performance by Koo. Photo credit: Taipei Arts Festival

Performance by Koo. Photo credit: Taipei Arts Festival

Part of the underlying suggestion would be that South Korean society itself is a pressure cooker on those living inside of it, as well as to gesture towards social alienation. Such thematics seem summed up in the talking rice cooker itself, an ironic appropriation of what is apparently symbol of late capitalist modernity in South Korea, as a form of anthropomorphization of a commodity. After all, returning to themes of capitalist alienation, also seen in Jocson’s Macho Dancer, workers and laborers can themselves be thought of as a speaking commodity.

August 14th

A TALK BY Tadashi Uchino was the first event today, with Uchino suggesting that theorist Hiroki Azuma’s concept of the tourist could shed light on contemporary theater works by Yudai Kamisato and contemporary dance by Choy Ka Fai. Taken together, this was to point to a way beyond the dead-ends of liberalism, nationalism, globalism, and empire, returning us to what is paradoxically an “impotent” subjectivity surrounded by “children”—representative of possibilities other than our own.

For Azuma, the tourist introduces contingency into the system of empire through the capacity of “mis-delivery” in being able to arrive at the wrong location or run into things unexpectedly. This disrupts the calculating logic of empire, perhaps widening the in-between spaces of nation-state and empire. Uchino raised the example of dialectics drawn from Dostoevsky’s planned sequel to the Brothers Karamazov, one interpretation is that, rather than end up as a terrorist as Russia entered revolutionary times, Alyosha becomes the impotent father of a host of children that are terrorists.

Talk by Tadashi Uchino. Photo credit: Brian Hioe

Talk by Tadashi Uchino. Photo credit: Brian Hioe

Yet despite his impotency, Alyosha still has force nonetheless, and this paradoxical agency of non-agency seems to be what Uchino is gesturing towards in his thinking. Uchino seemed to value the works of Kamisato in this light for featuring “minority” voices of Spanish actors in a ramshackle Japanese setting, with staging such that the audience sits anywhere and features of the stage are present all around the audience, complicating the interface between the audience and actors, as well as that Kamisato wrote his play from what he viewed as the perspective of the “tourist” by conducting research trips and sampling dialogue and scenery from his travels.

On the other hand, what Uchino seemed to value in Choy Ka Fai’s work, specifically citing a work in which Choy contacted the spirit of butoh founder Tatsumi Hijikata through an itako spirit medium and created a 3D work in which a dancer “embodied” Hijikata through motion capture, was the tension between authentic and inauthentic, comic and serious, in the work. Uchino also viewed this as a “touristic” work insofar as it involved Choy researching and absorbing various traditions including butoh, itako spirit medium culture, and a spirit returning to the corporeal as a “tourist.”

Panelists and members of the raised questions regarding to what degree one could, for example, be a tourist in one’s own country, whether tourism is as subversive as Azuma would have it, or whether capital accumulation is a necessary prerequisite for the act of engaging in tourism.

At night, we watched a performance of Ho Rui An’s Asia the Miraculous. Overall, the work proved a meditation on shifts in the conceptualization of Asia vis-a-vis the West, in which through past decades, Asia has been variously figured as a good student of the West, as an aberration from the West in terms of the strong role played by the state in the economy, or as something culturally or civilizationally deficient compared to the West.

More broadly, Ho suggested the means by which the West had failed to realize its own paradoxical conceptualization of Asia. The West seemed to see Asia as caught between modern, metropolitan, and cosmopolitan, while forever burdened by ancient tradition in such a manner that it would always prove temporally behind the West. Yet at the same time, despite use of Asian labor when it saw fit, such as the use of Chinese labor to construct the Transcontinental Railroad, periodic outbreaks of racialized anxiety against Chinese would also take place, as observed in the eventual passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act in America or contemporary anxieties about China’s rise.

Lecture-performance by Ho Rui An. Photo credit: Brian Hioe

Lecture-performance by Ho Rui An. Photo credit: Brian Hioe

Ho would go further to suggest that the contemporary rise of China evidences this pattern previously seen, of western anxiety and projection directed at Japan and the Four East Asian Dragons. Yet while Chinese global reach continues to expand, in evidencing a pattern of boom and bust already seen with other East Asian nations, rather than evidencing the “Asian miracle” or the triumph of “Asian values”, all this goes to further contribute towards the capitalist disenchantment of the world, or even provide for contemporary forms of haunting such as the rise of “ghost cities” in China. Panelists would later raise issues such as whether to think of Taiwan in a similar framework to other parts of Asia, whether China’s growth could continue indefinitely or would follow the pattern of Japan before it.

All this would perhaps show something of an eternal recurrence of history between the East and West, then, rather than unilinear historical progress which proceeds from East to West, as Hegel would have it, one might say.

August 15th

ATTENDED A REHEARSAL for Remote Taipei today, also taking part in it. In Remote Taipei, fifty participants are invited to wear headphones and follow the instructions of a voice on the headset AI as they move through Taipei. The AI directs them through the cityscape while also offering commentary on human life phenomena such as the spread of disease, old age and death, as well as themes as individuality, governance, free will, social structures, and intelligence.

It’s probably best not to discuss too much the sites we visited in the course of Remote Taipei, to keep it a surprise for anyone else who participates. However, part of the recurring themes of the performance was how individuals may feel more comfortable to carry out absurd actions as part of a group that they might not be willing to perform individually, such as walking backwards, taking part in a pseudo-political protest, or dancing in public places.

Self-portrait that participants in Remote Taipei were instructed to take. Photo credit: Brian Hioe

Self-portrait that participants in Remote Taipei were instructed to take. Photo credit: Brian Hioe

The locations for Remote Taipei were well-chosen, seeing as while the participants of Remote Taipei began in a park outside the city center, they were eventually brought to a surprising part of the city center. At one point, on Zhongxiao East Road, the AI began playing “Wandering Zhongxiao East Road for the Ninth Time” by Power Station. The AI also brought participants into historical sites as the Sun Yat-Sen Memorial and played recordings of speeches by Sun Yat-Sen. Likewise, the work also evoked a sense of the uncanny, particularly through defamiliarizing the actions of other humans, including of the other participants in Remote Taipei.

Nevertheless, despite engagements with some serious themes, the work, for the most part, retained a sense of play throughout. Although perhaps thematically different from other works in the program, given its focus on a staged sense of futurity rather than, say, contemporary issues of alienation and commodification of labor, this sense of fun generally seems to have been appreciated by the participants.

August 16th

AFTER SEEING a brief part of a rehearsal for Provisional Alliance on the first day of the festival, I finally had the chance to watch the entirety of the performance today. In the performance, different presenters make proposals of the audience, which plays the role of legislators. Audience members vote on various proposals to decide which advance and the various presenters advocating proposals also take turns interrogating each other. In between, various arcane legislative rituals are performed.

Proposals ranged from serious to comic, as well as from specific to abstract. At the performance I attended, participants included everyone from New Power Party city council candidate Chen Zhi-ming, who proposed greater participation in politics, to Dai Kai-Cheng, who proposed that open fields in urban landscapes be opened to free farming. Other participants included Pan-Sex, which called for greater discussion of sexuality in society, Jiang Yi-shao, who called for the decriminalization of public nudity, and Chen You-rui, who called for microchips to be installed in the necks of art school professors that would prevent them from saying the word “art.” Obviously, the last proposal seemed to primarily be comic, played for laughs as comedy, and while the others’ advocacy may have been more serious, all also engaged in dialogue meant to primarily be humorous more than anything, as pushed on by moderator Huang Ding-lun.

Photo credit: Brian Hioe

Photo credit: Brian Hioe

What came across from the performance, then, was perhaps a sense of the absurdity which sometimes result from democratic politics. After all, as anybody who has involved themselves in highly local politics can tell you, sometimes politics ends up being the domain of cranks. Getting that across may have been one of the underlying motives of the performance, seeing as while a serious discussion could no doubt result from any of the proposals—with the exception of Chen’s—this was far from what was aimed for.

Similarly, with various voting rituals, or oaths sworn by participants in a manner mocking of Taiwan’s numerous epithets, including “Republic of China,” or “Chinese Taipei,” part of the intent may have also been to point to the means by which parliamentary acts and governance are bound up with innumerable rituals that originate from history, but which can only but seem funny in the present.

The work was aimed at drawing the audience into the work, rather than have them serve as passive spectators, although the stakes for participation remained low. This was to involve spectators in the political process, perhaps pointing to the larger political processes that audience members are also implicitly part of. As such, the work was open-ended, although audience members may have come away with some new knowledge about certain social issues—if through the lens of comedy. With concerns running through the Taipei Arts Festival about governmentality and potential abuses of power by corrupt regimes, perhaps this work, too, gestures towards participatory politics as a remedy for this.

August 18th

FUN RUN would be a different event than the other events I attended, perhaps marking the transition from the Think Bar to the Taipei Arts Festival proper, as a space primarily for play, whereas the Think Bar was more focused on intellectual reflection. Fun Run took the form of Australian artist Tristan Meecham running a full marathon on a treadmill while local community performances took place around him.

The start of Fun Run. Photo credit: Brian Hioe

The start of Fun Run. Photo credit: Brian Hioe

Framed as an event in the memory of the run by the messenger Pheidippides to declare Athens’ victory over the Persian army in the Battle of Marathon, the event had a number of Greek trappings. This included that Meecham entered the stage wearing golden Greek armor, and as part of a parade preceded by a dragon dance. However, this was also meant to be humorous and festive, with dances set to pop music. Participating groups, which included a number of student groups, including cheerleading groups, hip-hop dance groups, fan dances, and other performances.

Photo credit: Brian Hioe

Photo credit: Brian Hioe

Despite the afternoon rain, this drew a fair amount of participants from the public, seeing as the event took place in the plaza outside of Zhongshan Hall and was free and open to anybody. Dancing took place both on stage and among the crowd, with dancers inviting members of the audience. Part of the humor of the event seemed to come from Meecham running a marathon and enduring the physical strain of this, as visible on the large screen projected on the stage set up for the event, but the overall tone of the event was light-hearted and fun.

August 19th

TODAY WAS the last day of the Think Bar, featuring a talk by Joanna Warsza on art and boycotts and a panel discussion afterward, which I was also on. Specifically, Warsza spoke on her experiences of the contested Manifesta 10 in Saint Petersburg, which saw a call for a boycott from artists that viewed Manifesta as complicit with the annexation of Crimea by Russia and rampant discrimination against LGBTQ individuals in Russia.

Warsza’s intervention was to call for critical engagement through Manifesta, rather than withdrawing it. Subsequently, she would edit the collection, I Cant’t Work Like This, on art boycotts and the conditions under which they emerge, raising several comparative examples inclusive of Manifesta 10.

As for me, I tried in my comments to bring the discussion to bear on Taiwan, in which art boycotts or other kinds of boycotts are infrequent as forms of protest, and in which direct action is much more common. Ironically enough, Taiwan’s current geopolitical status of official non-recognition is the result of a sort of boycott, after the ROC withdrew from the UN in protest for admitting China. But given its exclusion in many aspects of the international world due to Chinese pressure, Taiwan more often finds itself in the position of being boycotted itself. Taiwan’s geopolitical status could Itself be the object of boycotts but this rarely happens.

Talk by Joanna Warsza. Photo credit: Brian Hioe

Talk by Joanna Warsza. Photo credit: Brian Hioe

Jow-jiun Gong would also raise this concern, commenting on that one of the rare examples of a boycott in Taiwan took place regarding a 2004 biennale, and taking about issues with regards to how Taiwanese artists represent themselves abroad. Taiwanese artists abroad, after all, are susceptible to Chinese pressure as well, and it proves difficult for Taiwanese biennials to enter into global circulation among other such international art events. On the other hand, Liang-ting Kuo, would question whether it is already speaking from a place of luxury to think about art festivals and their relation to politics, as well as question direct links between movements and developments in the art world.

As this was the last event in the Think Bar series of events, perhaps it proves fitting, then, for this section of the Taipei Arts Festival to close on a moment of self-reflection on the nature of events such as itself. Indeed, opening with the Think Bar framed the arts festival as a moment for critical reflection, and hopefully the questions raised by it will be sustained through the rest of the festival. We will see going forward!