by J.Y. Kao

語言:

English

Photo credit: A-Mei/Amit World Tour/YouTube

ON AUGUST 1ST, 2016, a concert entitled “Love is King, It Makes Us All Equal” was held at Taipei Arena. Almost twenty thousand fans gathered at the stadium to hear thirteen pop stars performing their hit songs for the celebration of the Supreme Court’s rule on same-sex marriage. The last performer, who was also the core organizer of the concert, was Chang Hui-mei, mostly known as A-mei, an indigenous woman from the Pinuyumayan tribe (also called Puyuma) located in the East Taiwan region. A pop diva not only known in Taiwan but across the Greater Sinophone world, Chang Hui-mei has been an icon for LGBTQ communities since the early stage of her career. At the concert, when the overture of “Rainbow,” a song from Chang’s 2009 album Amit, began, the crowd burst into shouts and screams. A-mei called to the audience and asked them to raise their hands and sing “our [their] theme song together” with her.

As people in Taipei were wholeheartedly celebrating with Chang in such a carnivalesque manner, the significance of Taiwan’s gender politics and ethnic minority identity politics also rose to the fore of history. The concert event was unprecedented in Taiwan’s cultural history and marked a pivotal moment in the island’s democratization in terms of human rights since the 1980s. Taiwan was looking to be the first East Asian country to legalize same-sex marriage. Retrospectively, the meaning of the concert seems to have gone beyond simply a pop culture event: Why has Chang become a leading figure in Taiwan’s queer activism? What does it mean for a Taiwanese pop star with an indigenous origin to engage in the issue of gender equality in Taiwan? Is her ethnicity irrelevant to her engagement at all? Historically, the problematics of gender and the issues facing indigenous may lead us to discover a new theoretical potential in rethinking the island and the people who have made it the way it is today.

Settler Colonial Taiwan and the Making of Indigenous

TAIWAN, AN ISLAND off the east coast of China, has hosted and resisted a number of colonial forces from the Dutch in the sixteenth century to the Japanese whose colonization lasted from the late 19th century to the mid-20th century. Some would even suggest that the postwar presence of American military bases was a form of neo-colonialism. Because of the historical constructions left by the Western and Asian empires, Taiwan’s modernity has been a full-blown colonial one. After the official lifting of the martial law in 1987 and the disintegration of the authoritarian Nationalist regime, the small island stepped into an age of reconfiguring and envisioning itself as an independent nation free of colonial governance (though the Chinese government on the mainland has pressured the international community not to recognize it as such). Historians and literary critics have brought the concept of postcoloniality to define Taiwan’s existential and historical status—one example is the renowned scholar, Chen Fang-ming. [1]

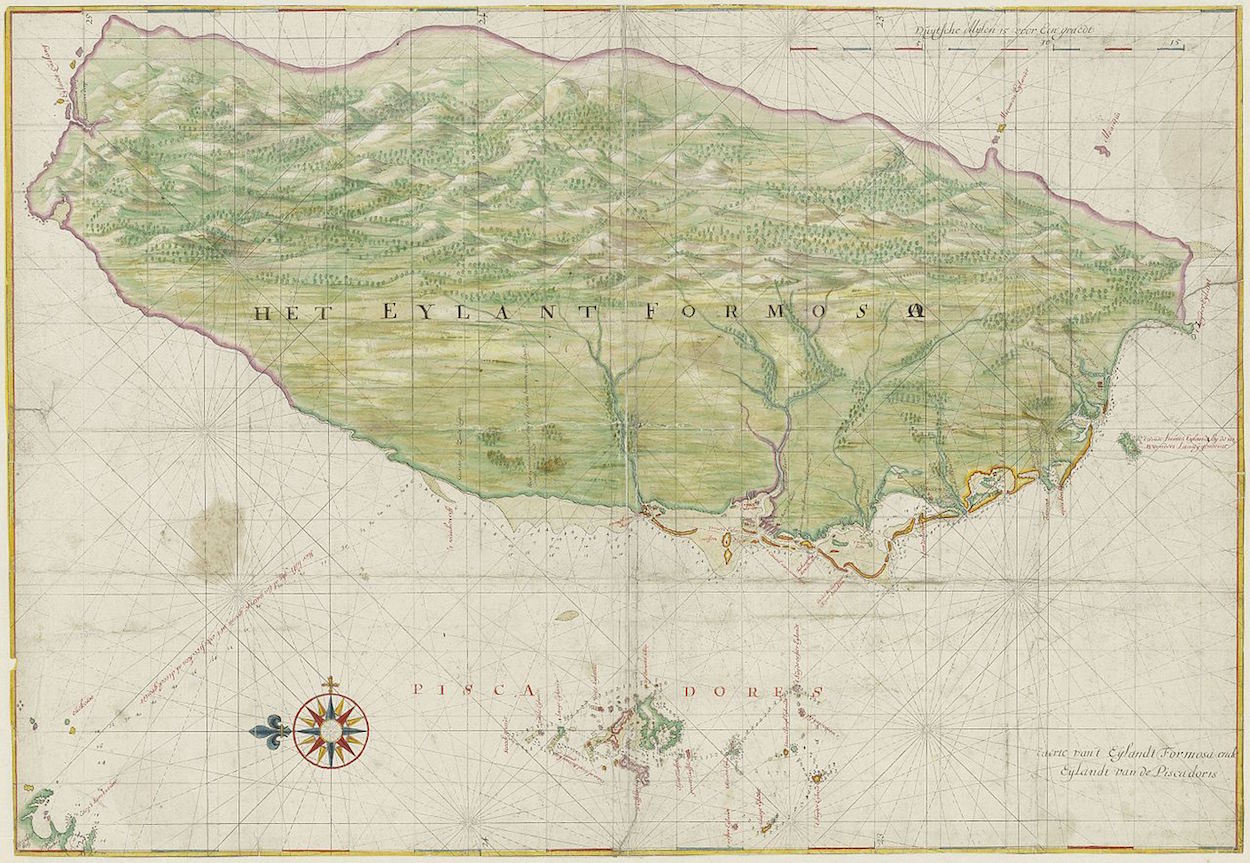

Dutch colonial map of Taiwan. Photo credit: WikiCommons/CC

Dutch colonial map of Taiwan. Photo credit: WikiCommons/CC

But one fact that has been often overlooked is that the postcoloniality of Taiwan can only stand valid from the perspective of Han people (a majority ethnic group originally from China). To re-view Taiwan through the lens of settler colonialism, we may immediately find that the island is far from being postcolonial, as the Han have become the predominant group while the indigenous population has reduced to merely two percent of the total populace. At the crossroads of empires, Taiwan’s multi-layered coloniality requires re-narration from different perspectives, especially when it is faced with the rise of China in the late 20th and early 21st centuries. Tang Chi-chie has succinctly calls Taiwan “the laboratory of modernities.” [2] Shu-mei Shih, using Lorenzo Veracini’s definition of settler colonialism, has also compared Taiwan’s similarities with and differences from the Western settler colonial nation-states. [3]

To specify one of the techniques utilized by the settler-colonizers, Carole Pateman develops the concept of the social contract in the colonial context and proposes “the settler contract” as a derivative and an extension of the European political tradition in the settlement colonies. Deploying a discourse of terra nullius, the white European settlers legitimize their occupation and governance of the indigenous. “The settler contract,” Pateman defines, “is a specific form of the expropriation contract and refers to the dispossession of, and rule over Native inhabitants by British settlers in the two New Worlds.” [4] For Pateman, the violence of settler colonialism is epitomized in the “maximum use of the colonized and their resources and lands.” [5] This occupation of material resources allows the settler-colonizers to “create a civil society” [6] and push the Natives into a “state of nature,” [7] by which colonization is beautified as the arrival of civilization and modernization for the “uncivilized” Native inhabitants. Under such contract which is a fictive construct unilaterally created by the white colonizers, the Native inhabitants are forced into the contractual relationship without consent. The option for them is none other than to obey and embrace the social order brought by the settlers. In Taiwan, an indigenous musician, Suming Rupi (1978- ) from the Amis tribe, once in a live performance satirized Han people’s takeover of indigenous land. Covering a famous Mandopop song and adapting the lyrics, Suming called to the Han people, in an ironic comic manner, to return the lost land. In this case, the Taiwan example echoes Pateman’s discussion of terra nullius as a concept that justifies the colonial conquest and occupation of the resources that do not initially belong to them. [8]

Whereas Pateman insightfully points out that the legitimation of colonization is based upon and produced by the legal and political discourse, her framework of the colonizer (or the colonist) versus the colonized (the Natives) seems inadequate in explaining the layered racial/ethnic hierarchy created by the contract. Looking historically at the structural making of the settler colony on the island would lead us to see that the dichotomous relationship between the Han settlers and the indigenous has never come as natural as in its Western counterparts; rather, it is a product of imperialist colonial rule from multiple regimes, each of whose policies has continually inscribed the marginality of the indigenous.

Before the seventeenth century, Taiwan, as a volcanic uplift from the sea, was not seen on maps of China. It was the European commerce traders who first found its geographical value in connecting Southeast Asia (Malaysia) and East Asia (Japan) around 1540s. The Portuguese first named it “Ilha Formosa” (“The beautiful island”). The Manchu empire, the last imperial dynasty of China, took it as its own in 1683 and later ceded the island to Japan after being defeated in the first Sino-Japanese War in 1895. Thereby, the beautiful island was transferred from the Chinese map to the Japanese map as Japan’s first full colony. [9]

Governor-general’s office of Taiwan during the Japanese colonial period. Photo credit: GB/WikiCommons/CC

Governor-general’s office of Taiwan during the Japanese colonial period. Photo credit: GB/WikiCommons/CC

During the 1930s, the Japanese intensified imperial subjectification (kominka) in order to speed up the transformation of Taiwanese into colonial subjects. In Japan’s disciplinary governing of the island, an ethnic hierarchy rose. Inheriting the Qing government’s rule, the Japanese elevated and institutionalized the hierarchy to a new level. With the Japanese on the top of the pyramid, the indigenous were also put under the Han Chinese. Beneath the Han were the “transformed barbarian” indigenous who had assimilated in the Han folkways, the “cooked barbarian” who were less Sinicized and lastly the “raw barbarians,” the indigenous with no connection to the Han society. To a large extent, the Han Chinese became the criterion in determining the degree of the indigenous’ civility. This organization of ethnicity buried the seeds for China’s claim to be Taiwan’s suzerainty. From this trajectory, the indigenous were transformed from “border peoples [of the Manchu empire] into modern ethnic minorities” vis-a-vis both the Japanese and Han Chinese. [10] Indigenous women played an inevitable role during the process. Many of them— often the daughters of tribe leaders— married outside their tribes and became the go-between interpreters between the colonizer and the indigenous. According to the official documents, indigenous women served as wives and “cultural translators” while still being labeled “barbarian.” The settler contract proposed by Pateman thus finds a more complex historical legacy in the East Asian context.

What Pateman’s theorization has failed to address the East Asian complexity and meanwhile the issue of gender and sexuality in the rule of settler colonizers. As Maile Arvin and her co-authors have pointed out, the settler colonial domination has often been a gendered process in which the indigenous women are reorganized into the heteropatriarchal order—as shown by indigenous wives. To make their indigenous feminist intervention, the authors write against the privilege of whiteness in the mainstream feminist discourse in the Western world. The inclusiveness of white-centered feminism has failed to create a level ground for women of color and indigeneity to voice their resistance to social repression based on their particular historical experience. By such an overlook, the logic of settler colonialism is reinforced. To counter the trend, the authors argue that settler colonialism, as a structure instead of an event, is correlated to the imposition of heteropatriarchy, setting out to erase the indigenous autonomy and kinship systems by assigning new gender roles to the “barbarian” citizens. In one’s resistance, the indigenous would need to oppose the heteropatriachal way of gendering along with the enterprise of settler colonialism. In one of the challenges posed by the authors to mainstream feminism, they state: “The heteropaternal organization of citizens into nuclear families, each expressing a ‘proper’ modern sexuality, has been a cornerstone in the production of a citizenry that will support and bolster the nation-state.” [11]

Seeing from the brief outline I present above, we find that inter-ethnic marriage has played a role in connecting the colonizers— be them the Japanese or the Chinese— with the colonized indigenous in Taiwan. This marriage system made possible the communication with and transformation of the indigenous. This colonial project of repressing the indigenous continued in a different fashion as the Nationalist regime suffered a defeat in the Chinese civil war against the communists after the Second World War and eventually relocated in Taiwan. From 1949 to the 1980s, a round of intensive Sinification swept the island, in which all inhabitants, including the Han Taiwanese who disconnected from mainland China centuries ago, and the indigenous who had never been in the picture of Chinese-ness, were also forced to identify themselves as “Chinese” under the authoritarian Nationalist government.

A-Mei performing in 2010. Photo credit: Public Domain

A-Mei performing in 2010. Photo credit: Public Domain

Going into the twenty-first century, although the Japanese have left the picture as an empire, the political tension between China and Taiwan has continued while Taiwan has evolved from a colony to a democratic nation-state. [12] This metamorphosis enabled the Taiwanese indigenous who used to be subsumed under the Han to make their cultural and political visibility in the era of Taiwan’s localization. It is in this background of Taiwan’s self-redefinition that Chang Hui-mei, the Puyuma girl, rose to the stage of Mandopop entertainment industry and changed the scene of Taiwan’s pop culture. From Chang’s appearance and development, we shall see how an indigenous star deploys a multitude of musical genres and visual tropes in her reinvention of a new Taiwan identity, implicitly refusing to conform to the Han-centric Chinese-ness propagated by the Chinese authority on the mainland.

From Chang Hui-mei to Amit

CHANG HUI-MEI (1972- ), born in a humble Puyuma family in East Taiwan, made her debut in 1996 with her first studio album Sisters (Jiemei). Sold over 800, 000 copies, the album marked a prosperous moment of the island’s cultural industry. Drastically different from the dominant Mandopop then, which preferred the female voice to be sweet, soft and touching as epitomized by the legendary Teresa Teng (1953-1995), Chang’s appearance with her active body movements and relatively rougher and higher vocal performance shook the audience’s ears. The first hit song, “Sisters,” diverges from the conventional lyrical style of popular love songs and features references to Chang’s childhood experience in the mountains.

Beginning with a Puyuma traditional tune sung by Chang’s mother, the song mixes Western dance music with Chinese lyrics. In Chen Chun-bin’s words, “A-mei’s aboriginal body and voice represented the exotica outside the Chinese world, so that A-mei was in a better position to speak of ‘world music’ than her Han counterparts.” [13] Because of the novelty from the combination of Western pop and indigenous elements, Chang began her Asia-wide tour, including in mainland China. But the overnight success suffered a setback in 2000 when Chen Shui-bian, Taiwan’s first pro-independence party leader, was elected President of the Republic of China (Taiwan). At the inauguration ceremony, Chang was invited to perform the Taiwan national anthem, which agitated the authority in Beijing. Consequently, Chang was banned from mainland China as a scapegoat of the political contestation between the two governments. Having lost the Chinese market made Chang rethink her career and identity. When she came back to the Chinese stage in 2005, a new mode of music production had been brewing in her, which was to bring the indigeneity to the front of her stardom image rather than merely as an accessory-like decoration.

In June 2009, Chang issued her fifteenth studio album, Amit. This time, Chang Hui-mei has disappeared from the cover of the album. What her audience see instead is a flame-red-hair woman, dressed in a white chiffon dress. She sits on a blood-red throne, looking to the right side of the frame. A ray of light catches her face and projects a deer-shaped, totem-like shadow on the back of the throne. Kulilay Amit— Chang’s Puyuma name—is split from the old image of Chang Hui-mei. The album integrates a wide range of musical styles, including heavy metal, punk and pop rock, and would shock anyone who is familiar with the A-mei idolized by thousands of fans. One of the hit songs on the album is “Double Cross” (“Heichihei”), which is written as a girl’s ironic comments on her boyfriend’s promiscuous games with other girls. After a series of Sadomasochism-themed images flesh back and forth, the music video, produced for the song, comes to the climax at which Amit beheads a man and walks into a door behind her. As the camera zooms out, the door turns out to be a vagina between a woman’s wide open legs. [14] The feminist rebellion is here manifested in the explicit portrayal of the female body . In addition to the sex innuendo, the album also presents suicide, death of the father, split of subjectivity and homosexuality— the gay-themed song later became the most popular song for Taiwan’s queer activism— to assemble issues from the public to the private. Eventually, the album concludes with a song entitled “Amit,” compiled with three Puyuma tribal tunes sung by Amit herself in the Puyuma langauge. Later, the rebellious, indigenous persona of Chang Hui-mei dominated the 2010 Golden Melody Awards, the Sinophone version of the Grammy Awards.

A-mei performing at Chen Shui-Bian’s inauguration. Photo credit: Apple Daily

A-mei performing at Chen Shui-Bian’s inauguration. Photo credit: Apple Daily

From the outset of Amit’s musical production, her concerns with gender— represented by “Double Cross” and “Rainbow”— stood out and has been closely linked to her indigenous identity. If the first album was to break the ice for Chang to re-present herself via a rebellious voice-making and visuality, her second experiment then pushes the boundary further. Six years after her debut, Amit released her second studio album, Amit 2, in 2015. Compared to the former one, Amit 2 is more elaborate and coherent in forming an overarching meta-articulation surrounding the artist and her music. This sequel not only inherits the rebellion and violence people have seen in the first one but also incorporates songs that highlight Amit’s non-conforming heterogeneity (“Freak Show,” “Guaitai xiu”), self-reflexivity on human’s self-contradiction (“Super Conflicted,” “Chongtudehen”), a harsh critique on contemporary internet culture (“What D’ya Want?” “Nixiang gan shenme?”) and, continually, a feminist outcry to heterosexist repression (“Matriarchy,” “Muxi shehui”).

The first hit song that drew the public attention was “Matriarchy”. The song presents a straightforward resistance against the social gendering of the female. Produced in the style of hard rock, the feminist message, formerly made in “Double Cross,” is now expressed in a more violent manner. The girlish female narrator in “Double Cross” seems to have grown into a woman whose criticism is now targeted toward the exploitation of the female.

我不會 耕田吃草 讓人下注 I don’t plow the field, eat the grass or let people bet on me

什麼理由 發明 什麼叫馬子 For what reasons did you invent the term “mazi”

難道是想讓匹馬為你生個兒子 Are you trying to have a son with a horse?

…

不要再說 要進廚房能出廳堂 Shut up! I won’t be your cook or your trophy

不要再說 要會鋪床又能著床 Shut up! I won’t make your bed and please you in it

這個世界沒有女人該怎麼辦 How would the world be without women

你想 你想 Think and think again on it! [15]

Speaking from the viewpoint of a domestically confined woman, the verse of the song starts off with a criticism on naming the female as “the horse” (“mazi”), an everyday slang commonly used by male to animalize— thus inferiorize and sexualize— the female. Meanwhile, the imagery of the son indicates the patriarchal obsession with carrying on the male lineage with a male offspring. Moving from a satiric tone to a direct critique on the domestic function of women’s labor, the chorus underscores an angry female figure who refuses to serve men for their needs. The crude-ness of the language employed in the lyrics is devoid of the sentimental mannerism in apolitical Mandopop music. Going together with Amit’s coarse voice, the song is performed to have a non-poetic aesthetic style that discards the lyrical subtlety and suggestive-ness. The style reinforces Amit’s persona as a feminist rebel who, in stark contrast to Chang Hui-mei, is no longer subject to the image of an entertaining pop star. Amit’s articulation has reached the audience’s ears as a harder and more straightforward punch.

Photo credit: A-mei/Amit

Photo credit: A-mei/Amit

The music video produced for “Matriarchy” also complicates the feminist cause by putting it in a visual narrative. Echoing the color contrast between red and black in “Double Cross,” the video of “Matriarchy” plays more boldly and prominently with Amit’s indigenous feminism. The beginning sequence captures Amit standing amid a cluster of red smoke. Slowly raising her head towards the light above, she is shown to wear a mask featuring indigenous totem patterns. Subsequently, the image shifts to a computer-generated sequence depicting a fetus growing in a uterus. As the fetus dissolves into a heart bumping rhythmically, a group of pregnant woman slaves appear working in the setting of a slum-like camp. They all have coal-dark skin and white hair, dressed in dirty robes. Several huge, swine-like men move among the women characters as overseers.

Some of the slaves are chained while others lay on the ground and the men’s whip lashes upon their bodies. Intercutting between the image of Amit, the fetus and the woman labor camp, the video goes on with a twist. When the slaves surround the men in circles, they take up the tools at hand and smash the men’s heads. Blood splashes like fireworks. Then, the women pile the corpse up and light a fire on it. As the bodies burn, all the women go into labor. Babies are born one after another. When the song ends, the video also freezes. In this last image, the woman slaves stand in a group. Each of them holds a baby in their arms. Amit, in the front, turns around and gazes into the camera. Four characters, “Muxi shehui,” appear with the logo of Amit in the middle.

The hyper-violent visual representation elevates the song to a shocking new level. Although the labor camp does not refer to any indigenous traditions, organizing the narrative in a montage with Amit as an indigenous goddess figure, the video demonstrates the intersection of Amit’s indigeneity and feminist resistance in a gothic fashion. The graphic portrayal of women’s rebellion under men’s exploitation and the leadership of the indigenous goddess converge in the last image in which the rise of women in disobedience is juxtaposed with Amit’s return of the gaze to the audience.

The gaze contains at least two meanings. For the male viewers, Amit challenges their authority over the female’s labor and body. For the female viewers, she calls upon them to act against the repression and exploitation embedded in the heteropatriarchal social order. Also, with the newly born infants, the women are all presented to be mothers free from the control of the father. As dystopian and mythical as it is, the video invokes the aesthetic of violence to depict Amit as the torchbearer of the Puyuma matriarchal system as well as the leader for feminist resistance. The song and its video may not address the Han people explicitly, but the indigenous feminism expressed here recalls the indigenous feminism envisioned by Arvin and the other authors.

Photo credit: Ah-mei/Amit

Photo credit: Ah-mei/Amit

However, Amit’s indigenous feminism is not totally comparable to Western indigenous feminism. As I have discussed earlier, the multi-layered historical repression on and invention of the Taiwanese indigenous not only comes from the Han Taiwan people but also was systematically produced by the Japanese in the past and reinforced now by the ascending Chinese empire. After releasing The Illegal Words in News Media Coverage (The First Edition) in 2016, Xinhua News, a state-owned news institute in China, issued another edition in 2017 and added fifty-seven banned phrases to earlier one. In Article No. 85, the document states: “The ethnic minority in Taiwan cannot be referred to as ‘yuanzhumin’ (‘the native inhabitants’). They can be addressed as ‘ethnic minority in Taiwan’ or by their specific ethnic names, such as ‘the Amis people’ or ‘the Atayal people.’ In official documents, they should all be referred to as ‘Gaoshanzu’ (‘the High Mountain Ethnic Peoples’).” [16]

On the one hand, for the Chinese authority to insist on the term “ethnic minority” (“shaoshu minzu”) is to incorporate the Taiwanese indigenous into the state discourse of mainland ethnic peoples who have been given the encompassing name since the early twentieth century, which aimed to recruit the ethnic peoples into the grand nationalistic project of modernization. [17] On the other hand, to ban the term “Native inhabitants” is to cut off the discursive possibility for Taiwanese to refuse their “Chinese” roots. This discursive manipulation fictively emphasizes the consanguinity of the one-big-Chinese-family narrative under the dominance of the Han majority. The attempt to homogenize the indigenous—thereby one step further in unifying Taiwan—is obvious on the Chinese side.

Amit could not have foreseen China’s censorship of the term which gives her ethnicity a historical legitimacy and visibility in contemporary Taiwan society. She also could not have resisted openly against the imposition of “the ethnic minority.” Retrospectively, however, Amit, or Chang Hui-mei, had already been clear about her identity as a Taiwanese indigenous, not necessarily with a Chinese forebear in the mainland. The production of two indigenous-themed albums, over the course of six years, was a timely cultural statement, if the political message is not so explicitly made. Mobilizing numerous musical genres, lyrics expressions and visual tropes, Kulilay Amit has successfully reinvented and reestablished herself not only as a pop icon but also an indigenous artist who has set out to revolutionize the soundscape and landscape of Mandopop industry.

In current international political status, Taiwan may have no leverage against the Chinese empire. Perhaps it is only a matter of time before Taiwan is devoured as part of the Chinese territory. As an individual, Amit has left her imprints in history by reaching out to millions of fans in Sinophone communities all over the world. Nations rise and fall, but Amit and her music would continue to shape and reshape our acoustic experience. Appropriating Michael Berry’s words, we may conclude that “beyond the ‘history that historians call history’ lies rich, multifaceted, and ever growing matrix of words and images that help us reconstitute stories what once seemed forever lost” and Chang Hui-mei/Amit has already been part of it. [18] All we need to do is listen, or even sing along.

[1] The non-Western scholars’ names have been written in the order that the family name goes before the given name, except for Shu-mei Shih who is an American scholar based at UCLA and who also spent her teenage life in Taiwan.

[2] Tang Chi-chie, “The Laboratory of Modernities: Reinterpreting Taiwan from the Viewpoint of Multi-modernity in World History” [“Xiandaixing de shiyanshi: cong duoyuanxiandaixing de guandian quanshi taiwan zai shijieshi zhong de yiyi zhi changshi”] in Knowledge, Taiwan [Zhishi Taiwan], Shu-mei Shih, Mei Chia-lin, Liao Chao-yang and Chen Tong-shen eds. (Taipei: Rye Field Publications, 2016), 95-140 [Taibei: maitian chubanshe].

[3] Shu-mei Shih, “An Attempt to Theorize Taiwan” [“Lilun Taiwan chulun”] libd., 68-78.

[4] Carole Pateman, “The Settler Contract” in Carole Pateman and Charles W. Mills, Contract and Domination (Cambridge and Malden: Polity Press, 2015), 38.

[5] lbid., 38.

[6] lbid., 38.

[7] lbid., 39.

[8] See the video clip of Suming Rupi’s performance at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oNmR7UXZ7V4. Visited April 30th, 2018.

[9] See Joseph R. Allen’s introductory chapter in Taipei: City of Displacements (Seattle and London: The University of Washington Press, 2012), 3-16.

[10] See the chapter, “The Longue Duree and Short Circuit: Gender, Language and Territory in the Making of Indigenous Taiwan” in Paul D. Barclay, Outcasts of Empire: Japan’s Rule on Taiwan’s “Savage Border,” 1874-1945 (Oakland, California: University of California Press, 2018), 114-158.

[11] Maile Arvin, Eve Tuck, Angie Morrill, “Decolonizing Feminism: Challenging Connections between Settler Colonialism and Heteropatriarchy,” Feminist Formations, Volume 25, Issue 1, Spring 2013, 14.

[12] Due to the limited space, I do not discuss the democratization movements in the 1980s Taiwan during which the single-party government collapsed and was replaced by a multi-party system.

[13] Chen Chun-bin, Voices of Double Marginality: Music, Body, and Mind of Taiwanese Aborigines in the Postmodern Era. Unpublished Ph. D dissertation (Chicago: The University of Chicago, 2007), 171.

[14] There are two versions of the video. The common one is a “clean version,” ending without the vagina scene that I invoke. The version that I refer to is collected in a premium edition of the album issued later. For the version that I discuss, please refer to: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bAss0bUsoGI.

[15] My translation.

[16] For more information, see: http://news.ltn.com.tw/news/world/breakingnews/2137777. The quote is my own translation of the original.

[17] To see more historical detail, refer to Jin Binggao, “When Does the Word ‘Minority Nationality’ [Shaoshu minzu] [First] Appear in Our Country?” republished in “Background Papers on Tibet: September 1992, Part 2,” Tibet Information Network, London, 1992.

[18] Michael Berry, A History of Pain: Trauma in Modern Chinese Literature and Film (New York: Columbia University Press, 2008), 383.