by Brian Hioe

語言:

English

Photo credit: Human Rights Network for Tibet and Taiwan

Tashi Tsering is the founder of Human Rights Network for Tibet and Taiwan. The following interview was conducted on February 8th, 2018, ahead of planned activities in Taipei for Tibetan Uprising Day on March 10th.

Brian Hioe: The first question I wanted to ask is, could you introduce yourself for people that don’t know you? How did you end up in Taiwan?

Tashi Tsering: My name is Tashi Tsering. I was born in India. I am a second-generation Tibetan exile. I have never been to my own country and never seen Tibet.

What left a deep impression was that when my parents went with the Dalai Lama to exile in Tibet, their aim was to return to Tibet. They may have felt at the time that it would only be a few months or a few years that the situation would be resolved and they could return to Tibet. However, up to now, we have no idea to return to our own country. My parents and the first-generation of Tibetan exiles have passed already away.

Tashi Tsering while giving a talk. Photo credit: Human Rights Network for Tibet and Taiwan

Tashi Tsering while giving a talk. Photo credit: Human Rights Network for Tibet and Taiwan

So again, I have never been into China. I actually never met any Han people while I was growing up in southern Indian countryside. But in India, by the time I was 18, I had participated in various human rights movements.

However, while my parents were still alive, I didn’t have the same aims I do now. My dream was to become a singer-songwriter. After they died, I felt very strongly that the dream of my parents had been to return to Tibet and I decided I needed to continue this.

Subsequently, I participated in the Tibetan Youth Congress. This is an organization that the Chinese government today continually claims is a separatist organization.

I learned much regarding human rights from this organization. I started to become concerned with human rights issues in Taiwan then. I knew that Taiwan had not developed very much in the way of democracy, since that was still during the authoritarian period. I had also a lot of skepticisms towards Taiwan.

At the time, Tibetans in exile did not really like Taiwan too much. Because in 1959, when we went into exile in India, our government requested aid from Taiwan. Taiwan was not very democratic them because of the KMT, of course. The KMT told us that, “Of course, we are concerned very much with Tibet. But we do not think that you are a country.” They saw us as part of the Republic of China.

This led people to dislike Taiwan. Nevertheless, I became interested in in Taiwan while in India. And I came to know that Taiwan started to have many democratic changes. That the elders of Taiwan spent a great deal of time and energy in efforts to change society and realize democracy and freedom.

The first time the Dalai Lama came to Taiwan was in 1997. I felt in my heart then that I should prepare to go Taiwan, because Taiwan had changed. That Taiwanese democracy had been established, so that I should go to Taiwan.

But it was quite tough for me in Taiwan, because I couldn’t speak Chinese. I didn’t know anyone. However, I thought it was very important, and that if I were to have the opportunity to go to Taiwan, I could establish an organization, and make connections with Taiwanese young people. As well as that it was possible that I could encounter Chinese students studying in Taiwan or Chinese people living in Taiwan. I thought it would be quite meaningful if I could communicate with them in Chinese. I had a lot of dreams like that.

Photo credit: Human Rights Network for Tibet and Taiwan

Photo credit: Human Rights Network for Tibet and Taiwan

So in 1998, I came to Taiwan. I was quite lonely, because of my lack of Chinese ability. My current Chinese ability I learned on the streets, I never studied it. That about sums up who I am.

BH: What kind of work does Human Rights Network for Tibet and Taiwan do?

TT: The Human Rights Network for Tibet and Taiwan was only recently established by me and some Taiwanese NGO workers. It’s only been around for half a year although we’ve been conducting activities for about a year. It’s been less than one year since we formally founded though.

You can find on YouTube the video about what we had been organizing in past years for Tibetan uprising day. We went from 7 participants to 3,000 participants. The first time we did this there were seven participants. But in 2009, there were 3,000 participants. In between, we did many things.

So there originally was the Tibetan Welfare Association and Tibetan Youth Congress. When I first came to Taiwan, there weren’t any organizations. So we later started the Tibetan Welfare Association, and the Tibetan Youth Congress.

The Human Rights Network for Tibet and Taiwan was formed later, because in the past years, many Taiwanese people, including civil society organizations and NGOs, have supported us. I wanted to see how I could help Taiwan. Because I am a nomad. I am trying to help my own country. But later, becoming a Taiwanese citizen, I wanted to start an organization to work with Tibetan NGOs across the world to support human rights in Taiwan. This can also represent Taiwan in the international movement for Tibet.

For example, last year in Taiwan, we organized a conference, with movement participants from Taiwan, Hong Kong, Tibet. That was something that Human Rights Network for Tibet and Taiwan and Students for a Free Tibet organized. The event was titled Freedom, Democracy, and the Right to Self Determination: Tibet, Hong Kong, and Taiwan Round Table Conference.

Whether Taiwan goes for independence or a middle path, what we confront in in Tibet, Taiwan, or Hong Kong is China. So we felt that we if we shared our experiences, we could learn from each other. The first dedication I had in this event was to Dharamsala. My aim with this is because Tibetan young people, second-generation or third-generation Tibetan exiles, don’t understand Taiwan. They think Taiwan was always a democratic country.

Photo credit: Human Rights Network for Tibet and Taiwan

Photo credit: Human Rights Network for Tibet and Taiwan

When Taiwanese people go to Dharamsala, they want to listen to Tibetan stories and understand where Tibet’s difficulties are. When Tibetans are in Taiwan, Tibetans will speak about their own country’s difficulties, but they don’t understand Taiwan’s difficulties. So that’s the first aim of the Human Rights Network for Tibet and Taiwan.

For example, in 2009, there was a wave of self-immolations in Tibet. But there have been self-immolations for a long time in Tibet as well. Cheng Nan-Jung self-immolated himself for the sake of Taiwanese independence. Tibetan young people should understand this. That elders in Taiwan worked very hard for young people to be able to criticize the government. Who would have dared, thirty years ago? This history is something young people should know.

That advocating independence is not so easy. But at the very least, that if we continue struggling, we can one day be like Taiwan. Among ethnic Chinese societies, only Taiwan is democratic. No matter whether you support Tsai Ing-Wen or Ma Ying-Jeou, voting to decide who is president is something that Taiwan has. China doesn’t have this. Much less Tibet, or Macau, or Hong Kong.

So Taiwan is democratic, but this was not easy to achieve. My point is you will achieve your goal if you work for it, so I think that many young people should see that Taiwan worked hard, is proud, and that we should do the same.

BH: Do you think there have been any changes in how the Chinese government treats Tibetans after the 19th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party?

TT: These are my personal views. The CCP pays no attention to the views and thoughts of the people. The representatives in the meeting that they claim represent Tibet or Mongolia are sent there by them to speak platitudes. There’s nothing to be gained from that.

I was talking to my student yesterday. We’re a government-in-exile stuck in another country. It’s a very small group of 150,000 Tibetans that constitute a country. Our leader currently is someone that we voted for as a people. Lobsang Sangay, our current president, was someone that was also in the Tibetan Youth Congress with me. But now he is our national representative, as voted for by the people.

The 19th National Congress is significant. We should have views towards this. But I also think that the Chinese government doesn’t have too much time left to trick the people. The people are more and more progressive.

Taiwan has had a democracy for thirty years now. By this point in Taiwan, since I started to participate in Taiwanese social movements, I have encountered many people from China, some as tourists, some doing business, some studying in Taiwan.

Photo credit: Human Rights Network for Tibet and Taiwan

Photo credit: Human Rights Network for Tibet and Taiwan

In the beginning, they didn’t want to pay attention to us. I often go to Liberty Plaza, or Taipei 101, or other places where there are many Chinese tourists. Now they read. But they say to themselves, “Don’t bring this home. It’ll lead to trouble.” Where does this trouble come from? Their government? They know this now. If the government doesn’t change, one day their children will oppose them.

This year, I am serving my third term as a member of the board of directors of Amnesty International Taiwan. When I go abroad to attend meetings, such as with members of Amnesty International, they are all very concerned with China-related issues. What about the Panchen Lama, then? He was only a six-year-old child. How could he be a political criminal? Or recently, Tashi Wangchuk. He only wanted to protect Tibetan culture, but now he’s been arrested. Or Liu Xiaobo, who was given a Nobel Peace Prize by the international community. He’s a child of China. But he was made into a political criminal by China.

Yet on the surface, the Chinese government manages to sound reasonable in the international world. I can understand very much, then, how what the Chinese government says and does are very different.

I don’t have any enemies. Chinese people or Han people are not my enemies. Whether Tibetan or Han, political prisoners are imprisoned until they die in prison. Our enemy is not the Chinese people. Whether Tibetan, Uighur, or Chinese, the Chinese government kills them all the same if they don’t obey. They kill their own kids.

BH: Have there been any changes in the Tibetan independence movement in Tibet in these past few years? The Chinese government is attempting to destroy Tibetan culture and crack down on cultural education. On the other hand, there are still self-immolations.

TT: For China to kill one Tibetan person, leads many Tibetan people to stand up. With China detaining Lee Ming-che, this has led many Taiwanese Lee Ming-ches to stand up. Despite controlling Tibet for 60 years, this hasn’t changed. Tibetans in Tibet haven’t given up. There are too many inequalities. That’s why there are inequalities.

For example, as a Tibetan in Taiwan, if I were to self-immolate, there may not be a response. I’m a Tibetan. As a refugee, I’m here in Taiwan. I don’t have roots in Taiwan. Tibetans than self-immolate do so in their own homes. They have their property, their community, their society. Why do they dare to self-immolate? Because there is too much oppression.

Photo credit: Human Rights Network for Tibet and Taiwan

Photo credit: Human Rights Network for Tibet and Taiwan

If you treat 6 million tibetans in China well and treat them equally, without discrimination between Tibetan and Han, Tibetans in China would probably think that the Chinese government is very good by now. They might have been brainwashed into forgetting their roots by this point.

But Tibetans in China continue to advocate strongly. They are forced to learn from how they are treated by the Chinese government. The Chinese government has spent a great deal of money on the Tibetan people. We are originally nomads. We have our traditional way of life. We don’t need houses, since we’re herders of sheep and cows, and etc.

The Chinese government wants to build houses for them. This is a way of controlling their movement, in tying them to the name. The Tibetans live upstairs. Below, they open stores, run by Chinese, as a means of control.

The Chinese government also tells Tibetans that they will educate their children, to bring them to Shanghai or Beijing. But this is a way of brainwashing. By the time these kids graduate from college, they no longer feel their are Tibetan.

Their Chinese is very good, and they graduate alongside Han Chinese. But when they apply to leave the country, they find they can’t. Because they are Tibetans.

The Chinese government says that self-immolations are being stirred up by the Dalai Lama. But how could the Dalai Lama do this? No organization would plan this.

If you don’t want Tibetans to self-immolate, this is up to the Chinese government. Within in an hour, they could stop this all. What do they want? It’s not hard. They want freedom of expression.

For many Tibetans, the Dalai Lama is not an ordinary person to us, he is a spiritual leader. Everyone has the right to decide their religious beliefs. But Tibetans are denied this right.

A Tibetan in Tibet is treated as an illegal. Do you know Woeser? She went back to Tibet from Beijing. Her husband is Han. After going back to Tibet from Beijing, she found she was not allowed to reenter Tibet. Han people can go to Tibet, but Tibetans aren’t allowed to enter. Tibetans have no way of enduring this. But they won’t give up on this either.

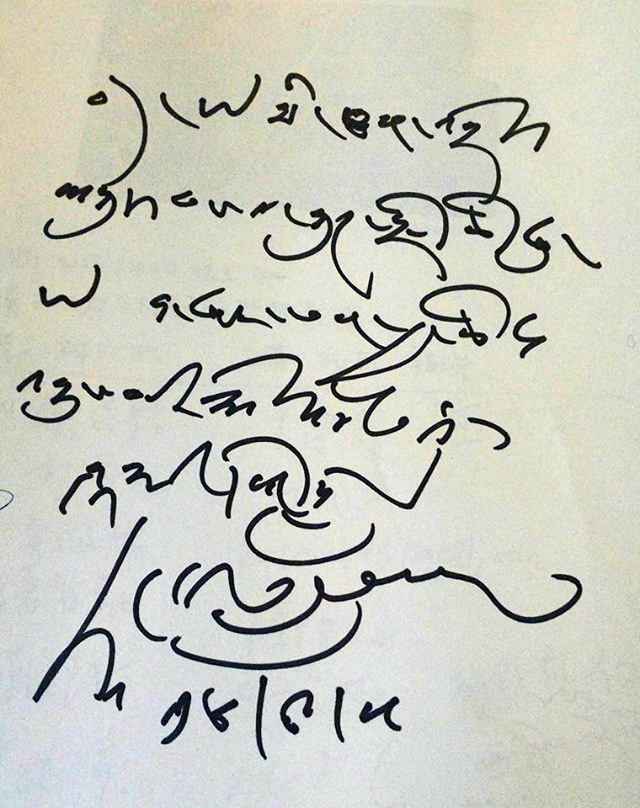

The Dalai Lama, Freddy Lim to the immediate left, and Tashi Tsering second from the far left. Photo credit: Human Rights Network for Tibet and Taiwan

The Dalai Lama, Freddy Lim to the immediate left, and Tashi Tsering second from the far left. Photo credit: Human Rights Network for Tibet and Taiwan

This may come from Tibetan Buddhist teachings. Because life and death are very much connected for us. Maybe you can live 60 or 70 years, but one day you have to die. That is definite. You have no choice. Maybe you can live to 70 or 80 and have a lot of money and build some very tall buildings or drive expensive cars. But you can’t choose not to die.

However, if you live to 70 or 80 or even 100, you should do something for everyone. I am doing something for my country, independent Tibet or whatever. But I never thought that this was only my country. I am a Tibetan. This is not my choice.

So it is a basic responsibility of mine, as someone born first as a Tibetan. When older, I decided that I was a citizen of the earth, and that I had a responsibility to the world. Afterwards, I will die. Maybe in the last minute you are alive, you’ll be thinking about what you did in your life. Maybe you own a lot of money, but this will make you very unhappy in your last moment.

But if you contributed something for your people or your country or the world, this will be comforting for you in living on this earth. As a result of this, I also don’t think that Tibetans will not be afraid and will not give up on this.

If you steal from others, maybe for a few hours, a few days, a few years, you may be happy. Yet you realize that you under pressure. One day, the tides of fortune may turn, and you will always be afraid. If someone has a gun, the most they can do is kill you, but this is different. When you start to think about hurting others, then you have pressure. Otherwise it’s not there. It starts from there.

BH: What issues facing Tibet and Taiwan do you think are similar? For example, after the KMT came to Taiwan, they repressed Taiwanese. And as you mentioned, many second-generation or third-generation Tibetans do not know how to speak Tibetan, whether they are Tibetans in exile or Tibetans within Tibet. Also, are there any differences in views between Tibetans in exile and Tibetans in Tibet, due to this separation of over 60 years?

TT: I also have limitations because of my age. When those that went to India first arrived, it was very difficult, particularly for the Dalai Lama. But because of the Dalai Lama’s efforts, our government-in-exile is now firmly established. These second-generation and third-generation Tibetans still can preserve our language and culture, because we live together.

Photo credit: Human Rights Network for Tibet and Taiwan

Photo credit: Human Rights Network for Tibet and Taiwan

The first-generation Tibetans worked in trade or as farmers. The second-generation, like me, started to go abroad to work and make money. This led to large changes in lifestyle. Originally, many were worried after many second-generation or third-generation Tibetans started to go to America or Europe. There were less and less people in India. What then?

These worries started in 1992, in these 25 years, after Tibetans started to go abroad. But now there are less worries. Because those that went abroad continue to be concerned with these issues, maybe moreso even. Because they’ve seen more of the world.

Like I said, I was born in southern India. I never encountered Chinese people before while living in India. The first time I heard Mandarin being spoken was the first time I went to Taoyuan International Airport. I’m serious.

When you see more of the world, you think about things more. And you realize that not having a country is something like a handicap. When you don’t have an identification, there are issues.

For example, Jeremy Lin. Some Taiwanese people will say that he’s an American. But it’s not exactly like that. Tibetans don’t have any nationality in that way. Whether second or third generation, Tibetans wouldn’t be able to become an American in that way. They would be a Tibetan holding American citizenship.

There’s this kind of sense of the nation in our education. You are always Tibetan until death. Then after death, you might be born as something else. So you don’t have that kind of choice.

I’ll give you another example. My elder brother was the first Indian to climb Mount Everest without oxygen. But he’s not indian. He’s Tibetan. However, we don’t have our citizenship, or identification, so I can’t claim this as an achievement for Tibet on an international level. So I must use some other citizenship to refer to this.

This leads to a feeling of that, “I need my country back.” During Olympics games, watching many countries’ flags there, we also would want to see our flag there. I might not be able to see us win achievements at such a high level, but at the very least, I would like to see us participate in this using our own flag.

Photo credit: Human Rights Network for Tibet and Taiwan

Photo credit: Human Rights Network for Tibet and Taiwan

That’s why we can never forget issues regarding our nationality. But because we seek international recognition, this is also why we wouldn’t seek to act as terrorists, as China claims.

Many people say that Tashi is a nomad. That’s true. I have no way of going to China. [Begins to sob]. But I can learn many things this way. It’s okay. The whole world has come to know the Dalai Lama. If there was no Tibetan Youth Congress, only the 6 million Tibetans might know the Dalai Lama. But now the whole world knows the entire world.

Dharamsala is a small place. But very important people, who have never been to India, come to visit Dharamsala because of the Dalai Lama. Scientists, world leaders, many kinds of people. This is a good thing.

The Dalai Lama is also a nomad. He has no passport. He has an Identity Certificate. I even have a better situation than the Dalai Lama, since I have a Taiwanese passport. He doesn’t have this. Everyone has advantages and disadvantages. It depends on what you want to use.

BH: Does the Taiwanese government do anything to help Tibetans in Taiwan? What kind of attitude does the Taiwanese government take towards Tibetans. The ROC system still exists, after all. How would you compare this to how America or India treats Tibetans?

TT: Like I mentioned, in 1959, the government then, the society then, was very different. This has changed. People have changed. Not just Taiwan, but the world. Some things are replaceable. If for some reason, McDonald’s was banned internationally, you would change to eating something else.

So the Taiwanese government then said that because Tibet is part of the Republic of China. But even then, this is what the constitution still says. To some extent, this has been annulled though. Tibetans use the Identification Certificate given to us by the Indian government, but the Taiwanese government accepts this as a way to give us visas. And although Taiwan doesn’t have a refugee law, 120 Tibetans along with me took Taiwanese citizenship, and some 90 people later on in another wave and another wave of 18. Taiwan has still helped out despite the lack of a law, in this respect. So for me, the help that Taiwan has provided is quite large.

And with regards to issues in which the Taiwanese government cannot directly make a statement, I can understand this. Because first, Taiwan’s president and its government’s first consideration, is the 23 million Taiwanese, not the 6 million Tibetans, or other issues.

An example is inviting the Dalai Lama to speak in Taiwan. Because there is pressure from the Chinese Communist Party, if there is no invitation, I would not think this is especially strange or be angry about this. You have your responsibility first to your own home, then to the world. I would not say anything. We can understand.

It is similar with arrangements by the American government to meet with the Dalai Lama that were fixed, but then later cancelled because of circumstances. We can understand that. Everyone has their responsibilities.

Photo credit: Human Rights Network for Tibet and Taiwan

Photo credit: Human Rights Network for Tibet and Taiwan

However, Tibetan society truly needs the support of Taiwanese society. Whatever happens in Tibet tomorrow, whether independence or a middle path, we would continue to confront China as our neighboring country. So Chinese, the language, will continue to be important.

Again, Tibetans in exiles only have Identification Certificates. Where do Tibetans in exile go to learn Chinese? There’s no way for them to go to Hong Kong, or Singapore, or Malaysia, due to our identification. There’s only Taiwan. Taiwan is very important in this regard. This will not change.

So as a Tibetan, I ask of Taiwan, please help us, if you are able to, and if there are no other pressures. In the future, there may no longer be this need. But this need exists currently.

BH: Next, I want to ask, what kind of connections to you have to other overseas Tibetan organizations in your work?

TT: There are Tibetan NGOs all around the world. But you asked about Asia in particular. As for us, our government is in India, and our organizations began in India before spreading globally. There are Tibetan organizations in Nepal. But in the past few years, the organizations in Nepal have encountered difficulties because Nepal is very close to China and experiences the influence of the CCP.

There are not any especial organizations in Hong Kong, but I have pushed for links between Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Malaysia, so I normally go to Hong Kong and help with events, and I communicate with Hong Kong social movement participants. There may be some lamas and a small number of Tibetans in Hong Kong, but there are not many, and it is very difficult. There is also Bhutan. Indonesia. The Philippines. And Thailand.

In Asia, during 2008, when the Olympic torch was touring for the Beijing Olympics, this was very advantageous for us. Because many human rights organizations in Asia protested when the torch was going around Asia, sometimes waving the Tibetan flag. This didn’t represent that they supported Tibetan independence necessarily, but that they supported human rights, and they no that Tibet has no human rights, which is why they would help out.

Photo credit: Human Rights Network for Tibet and Taiwan

Photo credit: Human Rights Network for Tibet and Taiwan

In the past, we would not have known this. That so many local organizations would help Tibet during the Philippines. Or in Indonesia. So this allowed the Tibetan government-in-exile to begin building a network. We discovered that many people in Asia supported us. This is particularly because in the past, we received more support from the United States and Europe, but after 2008, we discovered that we had quite a lot of supporters in various parts of Asia.

BH: How would you respond to criticisms that Tibetans in Tibet, whether in Dharamsala or other places, no longer represent Tibetans as a whole due to being outside of Tibet for so long? This may be compounded by increasing issues regarding language.

TT: I can explain this quite simply. Tibetans in Tibet don’t say that being in exile cannot represent them. This is something that China says, as a form of brainwashing. If the Chinese government really wants to say something like this, we might ask, what is Tibetan culture? You can’t learn this in schools, you are not allowed to teach Tibetan. How can you say, then, that Tibetans in Tibet can’t accept Tibetans in exile representing them.

We don’t talk in Chinese, it is not our mother tongue. We talk in Tibetan. I couldn’t understand Chinese either I learned it here.

The event we held last Wednesday was organized by Tibetans from Tibet, in fact. Sometimes they have Chinese phrases in the middle of their sentences. Like they might say “refrigerator” in Mandarin instead of in Tibetan, with everything else in the sentence being in Tibetan. They often don’t realize this. It’s not their mother tongue.

It must kept in mind that our president is voted for by our people, so China says this because they want to undermine our democracy, in questioning our authenticity.

BH: You’re recently working on Cycling for a Free Tibet. And Tibetan Uprising Day on 310 is also coming up. Can you talk a bit about this?

TT: Tibetan Uprising Day is held every year, and this is held in many places across the world. Every organization participates in this. What is special about this is that this is a platform for all organizations, with different views to participate, including those organizations that advocate for Tibetan independence, and those that call for a middle path. This is a shared space, not one in which there is any exclusion.

What is more particular about what we do in Taiwan is that in the lead-up to 310, we hold Cycling for Free Tibet. In the beginning, it was me riding alone. Because I thought this could be an opportunity to communicate with Chinese people, so I went to places with many Chinese tourists, such as Freedom Plaza, Taipei 101, the National Palace Museum. I would raise not only Tibetan human rights issues, but also Chinese ones.

Photo credit: Human Rights Network for Tibet and Taiwan

Photo credit: Human Rights Network for Tibet and Taiwan

Many Chinese friends have never heard of Liu Xiaobo. They would wonder who he is. So you encounter people like this. The Chinese people don’t always understand political persecution in China. Sometimes they actually learn in Taiwan. In this way, I hope that I can also help the Chinese human rights movement. I bring up people like Gao Zhisheng, the detained Chinese human rights lawyer.

Eventually, after Human Rights Network for Tibet and Taiwan was formed, we used this as the name of the organizing body. We also raise contemporary issues, such as the detention of Lee Ming-che, and other political prisoners. Some events we hold are responding to breaking news events, such as responding to what occurs in Taiwan, or China, or Singapore, and are not just regular events such as 310.

BH: What are plans for future events?

TT: As long as we have not met our goal, as long as I’m alive, we will continue to organize. Activities will not end.

BH: Lastly, what would you say as closing remarks? Not only to Taiwanese readers, but to international ones.

TT: What I would want to say is that they would use weapons in wars in the past. But there are many forms of war. Writers weave stories. The CCP spends a lot of money on writers, so they can issue propaganda, to make you believe falsehoods.

As a reader, you should be careful about what you read. You can’t believe everything. In Tibetan, we say that, because you have a mouth, you can eat anything, but you might end up eating what is poisonous. So you have to be careful what you read.