by Brian Hioe

語言:

English /// 中文

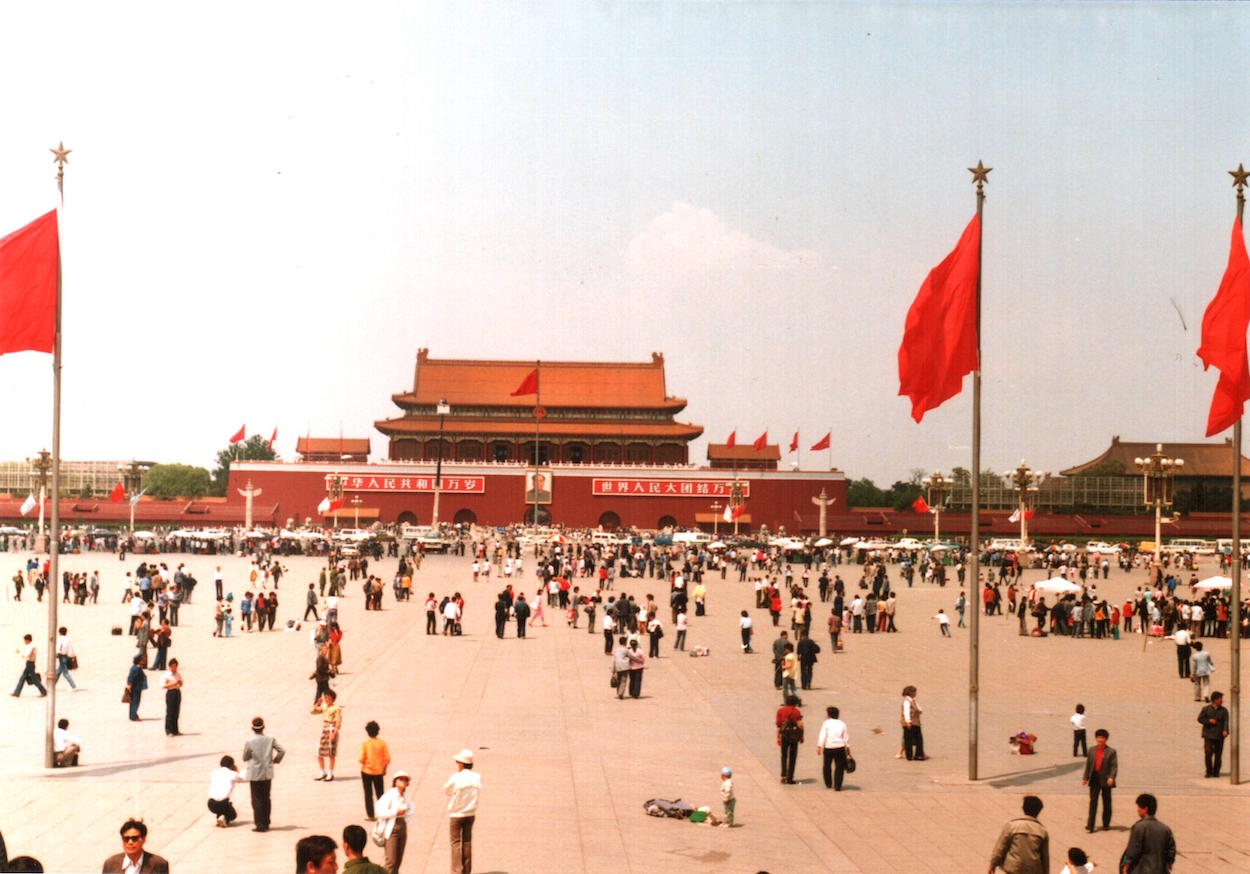

Photo Credit: Yinan Chen/CC

IT IS A strange paradox to observe the recent phenomenon of nationalistic Chinese netizens scoffing western critics of Donald Trump on issues as immigration, minorities, LGBTQ, and the environment as naive members of the “white left” (白左). Obviously, it is that for Chinese nationalists, the greatest obstacle in the way of China’s global rise is America. But nationalists of all stripe think alike and they recognize a kindred spirit in Trump.

It such, then, that one also sees why Chinese nationalists, despite sometimes referring to themselves as “leftists” because of China’s ostensibly status as a “Communist” country, scoff at those in China who concern themselves with the same issues taken up by the international Left, again, such as immigration, minorities, LGBTQ, and the environment. Namely, for such nationalists, this gets in the way of what should be the primary concern for China today–attempts at strengthening national power. They think this to be true of any other country, as well.

And so, while Trump may be the enemy, with his slogan of “America First”, with his casual demands for obeisance from all other countries, and even suggesting that he would consider direct extraction of oil from Middle Eastern countries, he also represents a model to be emulated for China. Indeed, the parallels between Trump’s strongman style of leadership and his dependency on a family network to support him draws parallels to the CCP’s style of rule. Some have pointed out in recent times, for example, that Trump’s use of his children and their spouses as lieutenants within his administration is highly reminiscent of the phenomenon of Chinese “princelings” groomed for government positions by their politically powerful parents–as his use of his political position to benefit his family’s financial empire. Chinese citizens have not failed to notice the similarities.

Photo credit: Derzsi Elekes Andor

Photo credit: Derzsi Elekes Andor

On the other hand, those concerned with social issues as immigration, minorities, LGBTQ, the environment, and other such causes are scoffed at by Chinese nationalists, whether these are members of the so-called “white Left” or individuals in China who take up such issues, But one also suspects that this sense of anxiety also ties into the fact that concern with immigrants, minorities, LGBTQ, the environment and similar social issues are never specifically national issues. The internationalist left has a way of cooperating beyond borders in a way that nationalists not only find foolish and irrational, but also probably fears to some extent.

There are nationalists both left and right. Likewise, not all nationalisms are cut from the same cloth; forms of civic nationalism tend to be rather harmless, even if there always remains the danger that relatively mild civic forms of nationalism may unpredictably transform into ethno-nationalism. And, again, “leftism” has particular nuances in China, in which the claim of the Chinese government to be a socialist government sometimes leads “leftism” to be associated with Chinese nationalism. But whether across the world or just within the Sinosphere, right-wing nationalists tend to think similarity. For example, while Chinese nationalists find themselves at loggerheads with Hong Kong independence advocates who embrace a right-wing form of Hong Kong nationalism exclusionary of Chinese on ethnic grounds, they, too are sometimes dismissive of the “leftards” they think of too hung up on issues as social equality or social justice. One can draw similar comparison to Chinese nationalists scoffing at the “white left”. And such individuals also see common ground with Trump, or the tide of right-wing separatism sweeping Europe with, for example, some, more right-leaning advocates of Hong Kong independence praising Brexit in the UK and seeing this as a model for Hong Kong to withdraw from China in a manner which will serve to expunge Chinese immigrants from Hong Kong.

But, of course, the mockery of the “white left” by Chinese nationalists or of “leftards” by Hong Kong nationalists also reflects the lack of any organized international left in the present. Likewise, mockery of the “white left” or “leftards” is in some way justified, because of the fact that too often has the Left shied away from seeking political power, but primarily focused upon cultural issues or various individual causes. The powerlessness of the international Left or the lack of any organized international Left is in many cases a product of retreating into the cultural sphere out of political powerlessness. In that respect, maybe right-wing nationalists are right to laugh. The international Left only has itself to blame for its powerlessness.