by Brian Hioe

語言:

English

Photo Credit: Film Still/Joshua: Teenager Vs. Superpower

JOSHUA: TEENAGER Vs. Superpower makes no attempts to hide that it is an attempt to lionize its titular character or that, as a documentary, it is a Hollywood-style film. And while capably produced, it has all the strengths and weakness of an attempt to make the chaos of a social movement into a Hollywood-style narrative, something Wong himself has remarked upon when asked about the documentary.

Beginning with Wong’s formation of Scholarism, the film follows Wong until the dissolution of Scholarism and formation of Demosistō in the aftermath of the Umbrella Movement, and the victory of Demosistō candidate Nathan Law in LegCo elections. The documentary features interviews with Scholarism leaders as Wong himself, Nathan Law, Agnes Wong, and Derek Lam, Benny Tai of Occupy Central, as well as prominent scholars as Jeffrey Wasserstrom and politicians as former LegCo member Martin Lee. The strongest element of the film is its organization and structure, in which the documentary is able to give a logical progression to a complex series of events, and track a large cast of supporting characters across a span of time without this ever becoming confusing.

Wong is, of course, heroized within the documentary as the lone hero who motivates his peers to stand up alongside him against China’s attempts at ideological brainwashing in Hong Kong and any focus on other individuals is merely to supplement the depiction of Wong. It is suggested within the film that individuals come to stand in for movements because it is easier to deal with a single individual to consider the complexities of a larger movement, but apart from suggesting awareness of this fact, the film largely continues in this vein.

Film poster for Joshua: Teenager Vs. Superpower

Film poster for Joshua: Teenager Vs. Superpower

Wong and his cohorts in Scholarism are the plucky rebels standing up against a godless evil Communist empire, then, with the narrative within the film that Wong’s efforts eventually led to the birth of the Umbrella Movement. Obviously, there is something quite amazing about Wong’s story, as a teenager who decided to take political action against the rule of the Chinese Communist Party at age fourteen.

But at times the film’s lays this on too thick, with quotes from Hong Kong chief executive CY Leung stating that “Forms of rebellious protest are futile”, quotes from Scholarism student activists directly drawing parallel to Star Wars. Or the suggestion Joshua Wong’s successes are through his great personal sacrifice in a vaguely Christ-like manner through the musical accompaniment for footage of Wong’s arrest during the attempt to retake Civic Square during the Umbrella Movement.

As with any documentary film which must construct a coherent narrative from the messiness of social reality, some elements have to be left out of the film. For example, internal conflicts which existed within the Umbrella Movement are minimized to only focus on tension between Wong and Scholarism with Benny Tai and the leadership of Occupy Central, with regard to Scholarism student activities being a more radical force which felt that Occupy Central was too rule-bound and failed to grasp the fluid nature of social movements. The tensions between different occupation encampments, such as between the mainstream leadership of the Umbrella Movement and the more anarchic Mong Kok encampment, are also left out.

Indeed, one cannot include everything, so some cuts are justified. However, at the same time, it strikes as lacking for the film not to include any criticisms of Wong whatsoever, something which would add to the film’s sense of reality when it already verges on seeming too much like a Hollywood drama. Similarly, some rather large omissions are made in order to simplify Wong’s background.

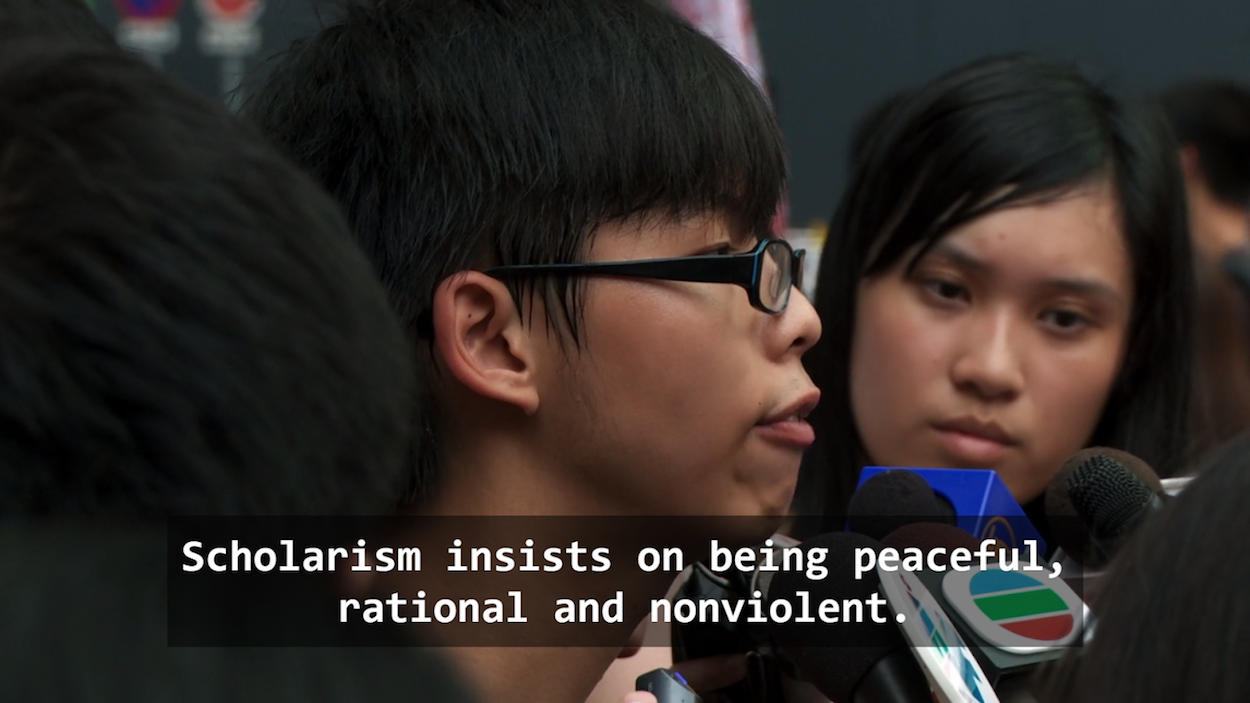

Film still. Photo credit: Joshua: Teenager Vs. Superpower

Film still. Photo credit: Joshua: Teenager Vs. Superpower

Wong is notably a Christian, something which the film does depict, but Wong’s father, Roger Wong, is also well-known in Hong Kong as an anti-gay activist. Consequently, it is rather strange, even dishonest, to see the film depict Wong’s parents as simple, humble parents with an extraordinary child when Roger Wong is a known public figure. Seeing as Roger Wong’s anti-gay activism has led Joshua Wong to distance himself from his father, it would add to the complexity of the film’s depiction of Wong if it went into the issue of how Wong politically relates to his father, whom the younger Wong credits for his political awakening by frequently taking him to visit the poor as a child, but whom Wong had to distance himself from politically in consideration of his father’s homophobia. Indeed, Wong’s Demosistō political party calls for the legalizing of same-sex unions and legal protections for transgender people in Hong Kong. Seeing as Hong Kong currently has no laws protecting sexual minorities, if Demosistō were to be able to pass this into law, this would be a milestone for Hong Kong.

And so it is the one-dimensional nature of the documentary’s depiction of Wong which is its greatest weakness. The film is at pains to heroize Wong and rightly so, given Wong’s extraordinary activism from an early age. But there is never any real sense that the documentary filmmakers have been given any special access into Wong’s subjectivity or personal emotional life. In part, this is not helped by Wong’s unemotional personality, as remarked upon by his Scholarism peers, who refer to Wong as “robot-like.” At times, even when commenting on his emotional state during the Umbrella Movement, Wong seems unexpressive.

But this seems like a failure of the filmmakers nonetheless, because the end result is that the depiction of Wong is one-dimensional. An individual as Wong, who was driven to student activism in his early teens, sacrificed his youth for political activism, and will never know what a normal teenager’s life is like, should be a complex and fascinating character. But there is never any sense that the film has grasped any of his complexity. And at the end of the film, one knows as little about Wong’s personal motivations for his activism as when one started the film. As such, so one sometimes suspects that the film’s true aims are much moreso be to serve as a primer to the Umbrella Movement for western audiences who may not know about Hong Kong’s situation rather than to serve as a character study of Wong. In this, again, it succeeds, even if it succeeds by virtue of greatly simplifying the Umbrella Movement.

Film still. Photo credit: Joshua: Teenager Vs. Superpower

Film still. Photo credit: Joshua: Teenager Vs. Superpower

In many ways, this makes “Joshua: Teenager Vs. Superpower” the filmic inversion of “The Sun Is Not Far,” the flagship documentary of the Sunflower Movement, which as an anthology film with no guiding connection between any of its constituent shorts, attempts to deal with too many complex aspects of the movement at once while also serving as a character study of a large cross-section of student occupiers, and with hardly any exposition within the movie at all. As a result, the film is largely an incoherent one, but when compared to the one-dimensional narrative of “Joshua: Teenager Vs. Superpower”, one has the sense that it is much more earnest as a documentary. Indeed, when it comes to unfiltered documentary depictions of the Sunflower Movement, a series of documentaries have also been produced on the life of student leader Chen Wei-Ting, which depict Chen warts and all, including his sexual harassment scandal, and focus on Chen’s perspective through his turbulent political career.

Yet with its international release on Netflix, “Joshua: Teenager Vs. Superpower” will see broad reach and, as an introduction to the events of the Umbrella Movement for individuals with no knowledge of the Umbrella Movement or Hong Kong, it is a useful one. If this is the true aim of the film, then, it is a successful one. But if the aim of the film was indeed to serve as a compelling and three-dimensional portrait of Joshua Wong the individual, as it claims, it is an utter failure.