by Alex Wen

語言:

English

Photo Credit: Film still

This article will kick off a series of features that will explore the films and figures that have defined and continue to define Taiwanese cinema and culture. Taiwan’s unique history and late entrance into the global film sphere has allowed the island to play host to a myriad of hidden gems worth highlighting. Join us as we delve into the minds of Taiwan’s greatest directors and see how they bring the country’s identity, people and culture onto the silver screen.

ALONG WITH the In Our Time omnibus released in 1982—to which Edward Yang contributed a short, That Day, On the Beach set the groundwork for much of the Taiwanese New Wave of films to come. The early years of the 1980s were a time of rapid technological development in Taiwan, particularly Taipei. While his contemporary and fellow pioneer, Hou Hsiao-hsien zeroed in on the plights found in the countryside, Edward Yang held a fascination with the lives of affluent city-dwellers—one that would span his entire filmography.

Born in Shanghai, Yang’s family moved to Taipei when he was a toddler. After getting a degree in engineering, Yang worked in America until he relocated back to Taiwan to pursue his passion for film. His rootless youth mirrored the rapid changes that were occurring in Taiwan at the time, and these themes of roots, home and identity would play a crucial role in his directorial feature debut, That Day, On the Beach.

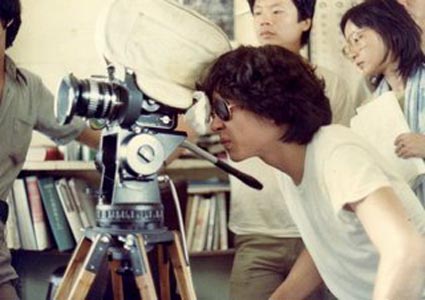

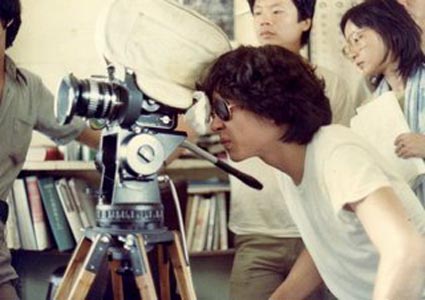

Yang on the set of That Day, On the Beach

Yang on the set of That Day, On the Beach

The film is a sprawling family drama told in flashbacks. When two high school friends, Jia Li (Sylvia Chang) and Tan Weiqing (Terry Hu), reunite after 13 years apart, they reminisce about their youth. Li was once in love with Weiqing’s brother, Jia-sen, but the couple were forced to separate after Jia-sen was forced into an arranged marriage. Devastated and heartbroken, Li funneled all her energy into her then-budding piano career, which resulted in her studying and working in Europe. Seeing her best friend and brother unhappy, Weiqing becomes increasingly anxious as her own arranged marriage date approaches. Late one night, she meets with Jia-sen, hoping to find answers. With a head-on shot of Jia-sen—as if he were addressing the audience—he musters up a few anecdotes about stability and embracing simple pleasures. His heart is not in it, surely thinking of what could have been, when Weiqing interrupts with a “Are you happy?” And in that moment, Weiqing appears incredibly small and naive. She was always the younger sister of the group, but here, compared to the exhausted Jia-sen, she’s brimming with youthful optimism. He retorts, “What is happiness?” Weiqing runs away from home the next morning.

Edward Yang is a patient director. With streaks of Ozu in him, each scene is a slow-moving medium shot. Yang is rarely bothered by where the narrative is. He frequently travels with the emotions of the characters, following through their thought-process, into flashbacks or taking a shortcut with minor characters. Yang needs to address what happiness is, and the answer seemed clear with Weiqing. She runs away and marries her high school sweetheart, the silly but honest Cheng Dewei. They do well in the first few years, with Dewei consistency performing well at his work. But this doesn’t answer the question. And as Yang digs into the emotional mind of Weiqing, it becomes clear that the answer may never arrive.

Still from That Day, On the Beach

Still from That Day, On the Beach

The bulk of the film sees their marriage deteriorating. Dewei is swamped by work and stress, and Weiqing, as a woman, has been typecasted into a supporting role by society, yet she has no one to support. Dewei often comes home late and drunk, if he comes home at all. Suspicion that Dewei might be cheating on her consumes Weiqing’s mind, and it’s only further fueled by her idle role as a housewife with no husband or child to take care of. Edward Yang, along with screenwriter Wu Nien-jen, makes it clear that not only does capitalism oppress hard-working people, it disproportionately eats away at women more. Women are fed the same delusions of grandeur and hyper-consumerism that occupies the mind of all salarymen, but they also have to face the scorn of the working men, who oppress their wives in a vicious bid for power. And perhaps few people would be more aware of this reality than Weiqing. She saw a perfect couple split up, and she’s tried the rebellious, romantic path, only to find it lead to the same ending. At one point in the film, she sighs and states, “Our society tears men and women apart.” And it’s jarring to find her say it with such conviction. Other than her early act of defiance, she’s always been passive and accommodating. To see this transgression, a great believer in love, broken down and punished for her belief, is to witness Yang’s quiet prowess. Nothing is devastating all at once, rather it’s the slow, creeping process that is frightening. After all, we fear what we can’t anticipate.

It’s easy to see all this as an indictment of the rapid industrialization Taiwan was undergoing during this period of time, but Yang implores the audience to look deeper. He offers the prototypical couple with Li and Jia-sen, only to have them broken up by a traditional system. He then proposes the rebellious, contemporary couple—Weiqing and Dewei. And yet, they meet the same, if not worse, fate. After many years of being colonized by various powers, Taiwan’s identity has become slippery to grasp; attempts to hold on to the past only blocks progress, but welcoming the booming technology sector seems to erode any personality that had made Taipei and Taiwan unique. Yang makes this clear in the ending, where Jia Li and Tan Weiqing find contentment by being free from men, free from patriarchy, and free from the system. But by the same token, they both escaped by doubling down on their careers. Taiwan can focus on developing its own unique brand and image, but it’ll remain trapped by the larger systems at play.

Yang may express an exacerbated sigh towards Taiwan’s state of hyper-consumerism, but there’s actually quite a bit of humor to be found in That Day, On the Beach. Some of it is absurdist humor, watching these pathetic humans try to piece together love and warmth in the cold, uncaring big city, but a lot of comic relief comes from the acts of humanity that manages to shine through. It’s similar to how the Coen Brothers danced between the funny and the violent in Fargo or how Charlie Kaufman injects dark humor into his nihilistic projects—as with his latest, Anomalisa. All these directors, including Yang, feel indebted to include some sense of humanity in their projects, less so to comfort the audience, but to highlight how far our society has strayed from its virtues. Granted, any argument on morality becomes a rabbit hole down righteousness and duty, which is why all these films zero in on the most basic, yet most intangible quality—happiness.

Films, as with most commercial endeavors, are rarely at the forefront of critical theory, but few mediums are more in tune with the pulse of the human condition. Happiness sits as a confuddling paradox, the more mind you pay to it, the less of it you experience. Happiness has been commodified and mass-produced in such a way that it’s hard to discern what happiness actually means anymore. Dewei certainly couldn’t see it, pressed into taking longer hours with the carrot of promotion in his future. This might be a reason why Edward Yang was infatuated with the depiction of the middle-class. It’s a demographic with enough time to idle about and think about purpose and reason, but not nearly rich enough to ignore the constant pressures that money imposes.

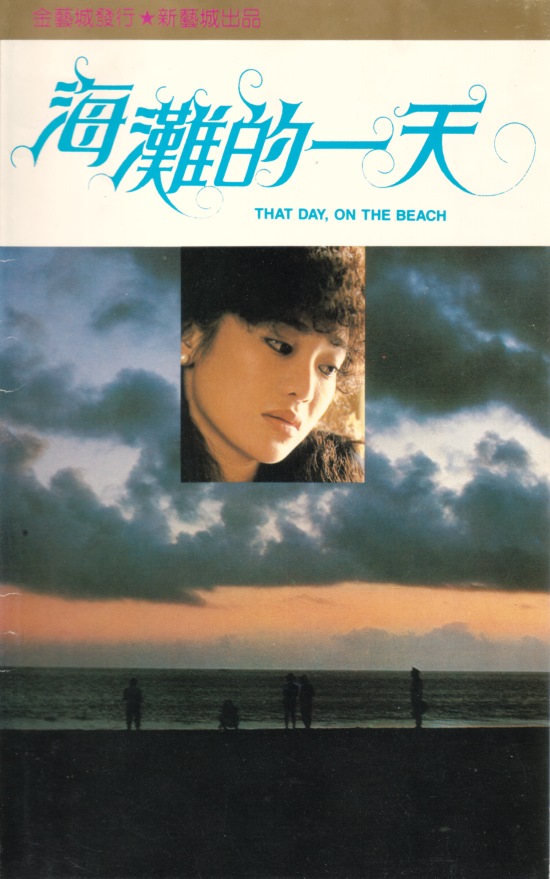

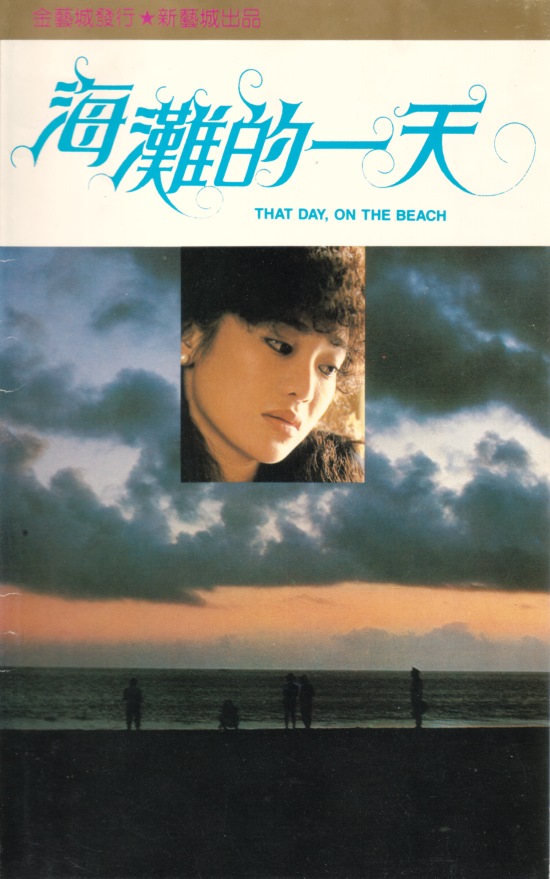

Film poster for That Day, On the Beach

Film poster for That Day, On the Beach

Ten years after That Day, On the Beach, Tsai Ming-liang will usher in the second wave of creatives in Taiwan with Rebels of the Neon God. It’s a radically different film on the restless youth to the backdrop of urban decay. Ten years seems to have changed little; both directors are looking at the same Taipei—a city that’s become a beacon of success, but at what cost? Yang will continue to press on these ideas of happiness and identity throughout his career, capping it with his magnum opus and sole international breakout, Yi Yi. And so Edward Yang leaves us, both in the film and in real life, still pondering on what exactly happiness and home are, where our roots and identity lie. Does free will guarantee contentment? Is happiness a concept for children, and children only? Perhaps it’s only through these questions that we can escape the mundanity of reality. If so, then That Day, On the Beach may be one of the most alive directorial debuts, befitting to start a movement.

Yang on the set of That Day, On the Beach

Yang on the set of That Day, On the Beach Still from That Day, On the Beach

Still from That Day, On the Beach Film poster for That Day, On the Beach

Film poster for That Day, On the Beach