by Brian Hioe

語言:

English

Photo Credit: Addiction

Why The Ban on Depictions of Homosexuality in Chinese Media?

THE LATEST sign of increasing restrictions on media in Xi Jinping’s China would appear to be the recent ban on depictions of homosexuality on television, along with depictions of underage relationships, one night stands, and extramarital affairs. This is hardly the first time under Xi’s rule we have seen seemingly arbitrary restrictions on media with, for example, official disapproval of depictions of “time travel” in 2011. The recent restrictions also include the banning of depictions of smoking, reincarnation, and drinking, among other things. But why is there such interest in regulating sexuality in contemporary China?

As outlined in a classic work such as Wilhelm Reich’s 1933 The Mass Psychology of Fascism, there would seem to be a strong connection between sexual repression and authoritarian regimes. Sexuality is seen as a potentially socially destabilizing force, with the view that sexual desires can lead to irrational behavior if left unchecked that can potentially lead to revolt. The disciplining of an individual’s sexuality, then, becomes a crucial foundation for disciplining the individual’s attitudes and providing for their ultimate submission towards authority. We see this quite in the history of the 20th century authoritarian regimes with the regulation of sexuality in Nazi Germany and Stalin’s Soviet Union.

Under the Xi Jinping presidency, we have seen a renewed emphasis on Chinese nationalism, framed as the return to Maoist fundamentals. In line with this can we understand China’s recent steps to curb what its leaders must view as overly permissive sexual attitudes from the West that have led to a weakening of the nation.

Still from Addiction, also known as one of the television shows affected by the ban. Photo credit: Weibo

Still from Addiction, also known as one of the television shows affected by the ban. Photo credit: Weibo

In particular, young people are seen as having been too influenced by western media and western cultural attitudes since the free market reforms of the Deng era and the opening up of the country. It is such that young people must be made to learn proper traditional values where sexual attitudes are concerned, to curb what is seen as decadent, western, and harmful. After all, attendant with the opening up of China came relaxation of sexually puritanical views. A part of this was the importation of western media into China, or media imported from other East Asian countries and territories with more open social norms, particularly from Taiwan and Hong Kong in the past, but more recently with the popularity of Korean dramas.

There would be few examples of sexual repression on the scale of 20th century China, given the unprecedented nature of the One Child Policy as a social engineering project aimed at regulating reproduction. The effects of One Child Policy are often viewed monolithically by western observers of China, for example, neglecting the fact that enforcement of One Child Policy varied from region to region in China and some individuals chose to pay fines have multiple children, or were able to have multiple children because party officials turned a blind eye. Yet there generally seems to exist few parallels in human history of this kind of population engineering project.

But with the call for a return to Maoist fundamentals, it must be that decadent and libertine sexual attitudes seen as originating from the West now must be curbed. We see similar calls in Russia under Putin, with the persecution of homosexuality and the emphasis on a return to the traditional family on the rise with resurgent Russian nationalism that harks back to the glory days of Stalin’s Soviet Union.

Policing of Sexuality in Mao’s China and Xi Jinping’s China, Silence from Critical Voices

IRONICALLY, Chinese New Leftists or Neo-Maoists have juxtaposed past gender equality under Mao and present gender inequality as a one of the outcomes of unfettered capitalism in China. We may point to the contemporary phenomenon of “leftover women” who are socially looked down because they are unmarried, for example.

In truth, such individuals could have been more critical. It is true that the rampant gender inequality we see now in China did not exist in the Mao period. But the return of traditional patriarchal attitudes after the Mao period actually means that the Mao period had never truly gone far enough in exterminating such attitudes, if they could resurface so quickly after its end. And gender inequality has been accentuated to an extreme extent because of the uneven social demographics wrought by Maoist social engineering projects which occurred on a grand scale, including One Child Policy or the Great Leap Forward.

Ironically enough, uncritical nostalgia leads to a selective forgetting of this fact, particularly with accusations of Orientalism or pro-western bias deployed against those who pointed out China’s past history of sexual repression in the One Child Policy. But the case of recent bans on depictions of homosexuality on television may suggest that while there is nostalgia for “Maoist feminism,” Maoism was never quite so socially progressive where issues of homosexuality were concerned.

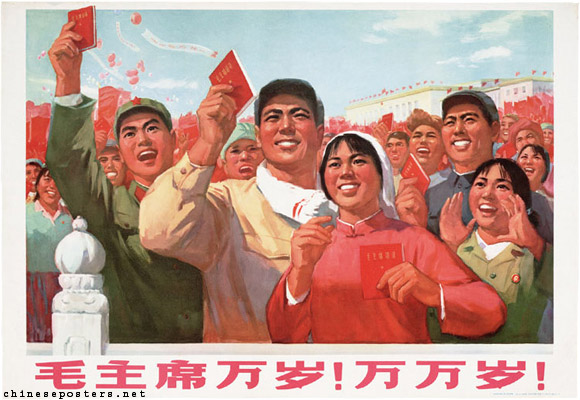

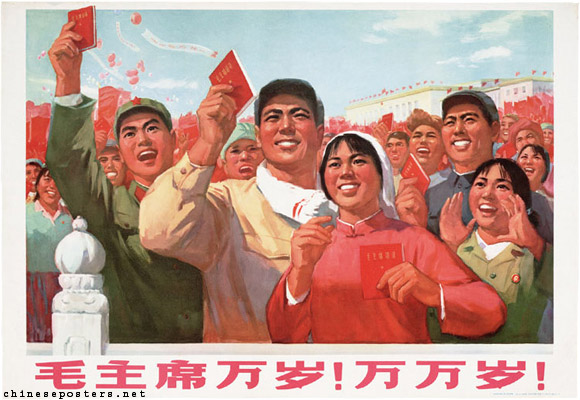

Maoist propaganda poster. An emphasis on the heterosexual family is a common element of Chinese socialist realist art. Photo credit: Chineseposters.net

Maoist propaganda poster. An emphasis on the heterosexual family is a common element of Chinese socialist realist art. Photo credit: Chineseposters.net

It is no mistake that open homosexuality occurs concurrent with the capitalization of China which occurred in the Deng period. Maoism still enforced normative gender norms, focused around the assertion of a normative sense of masculinity and femininity. Homosexuality, trans, or non-gender binary forms of sexual and gender identities were not allowed to emerge in urban or other spaces under the Maoist period. The flipside of the higher gender equality which existed in China during the Mao period only with the breakdown of the Maoist paradigm and the capitalization of China that greater sexual freedoms were allowed to emerge in China. As such, uncritical nostalgia for higher gender equality in the Maoist period has sometimes occluded discussing attitudes towards homosexuality, trans, or non-gender binary identities in the Maoist period.

The irony would seem to be that the New Left is in a position of power in China currently where it could leverage the critique of the Chinese state’s actions. But if in the past the New Left was critical of rampant capitalism in China, now that it is in power, it at times acts as apologists for Chinese state capitalism. With recent incidents of feminists and women’s rights activists persecuted as threats to the authority of the state, the New Left could be a more vocal force of critique, but it faces the dilemma that it cannot really go against the regime now that it is ostensibly in power. Despite appearing to be in power, like any other interest group in Xi Jinping’s China, the New Left could be purged, after all. But this leads to a silence on such issues.

We shall see as to what happens in China’s future, then, in an era in which the policing of sexuality on a mass scale is back on the table. Certainly, as we see in the ban on depictions of homosexuality in television, this would seem to be what we see with Xi Jinping’s China.

Still from Addiction, also known as one of the television shows affected by the ban. Photo credit: Weibo

Still from Addiction, also known as one of the television shows affected by the ban. Photo credit: Weibo Maoist propaganda poster. An emphasis on the heterosexual family is a common element of Chinese socialist realist art. Photo credit: Chineseposters.net

Maoist propaganda poster. An emphasis on the heterosexual family is a common element of Chinese socialist realist art. Photo credit: Chineseposters.net