by Brian Hioe

語言:

English

Photo Credit: Citobun/WikiCommons/CC

Accusations of Fascism Yet Again from the Pro-Unification Left

WRITING IN 1951, six years after the end of World War II, philosopher Leo Strauss coined the term “Reductio ad Hitlerum” to describe the tendency in an argument by which one attempts to disprove something through a comparison to Nazism. This would be a form of association fallacy, by which one attempts to stir up fear about something by comparing it to Nazism or fascism and in this way suggest that it is unequivocally wrong, but establishing this primarily through guilt by association. This is also known today as “Godwin’s Law”.

We might say that recent attempts to compare the Mong Kok riots on February 9th in Hong Kong to “fascism” by Tan Kin Ling (鄧健苓) writing in Coolloud and Lee Wing Chun (李峻嶸) writing in Initium are illustrative of this principle. One suspects neither Tan, Lee, nor others have any real sense of what fascism is. Instead, as members of the pro-unification Left in Hong Kong or Taiwan do quite frequently, at the core, anything which resists China is deemed to be “fascistic” or “populist” in their eyes.

On the contrary, in English, we have a term to refer to such people, which is “tankie”. “Tankies” are the self-proclaimed Leftists that defend authoritarian regimes claiming to be Communist such as the Soviet Union and China so uncritically, even when criticized by other Leftists, that these people will be cheering on when the tanks come rolling in and mowing down students. Indeed, Tan may devote a lengthy section of her article to reviewing the history Hong Kong police as an enforcer of the state both under British colonialism and after, partly in order to deconstruct the perception that the police were necessarily better under the British. But we might turn this question around nonetheless in asking, if fascism is such a threat, would she see it as better if such “fascists” were taken down by the enforcers of the state? Tan largely evades this question.

In particular, Tan and Lee’s fears are raised by the rise of “localism” in Hong Kong, as foregrounded by the recent riots in Mong Kok in which localist groups played a significant part, also known as the “Fishball Revolution”. “Localism” consists of political forces calling for greater political autonomy for Hong Kong from China, but localism is distinguished from other political tendencies in Hong Kong calling for political autonomy through calls for an radical escalation of tactics to accomplish this. Sometimes the implication is that the use of riots or violence would not be off the table.

Localist groups are also differentiated from other political tendencies in suggesting fundamental differences between a Chinese and Hong Kong sense of identity, as sometimes founded upon claims about ethnicity, and calling for proposing more radical solutions to Hong Kong’s relation to China, such as Hong Kong independence.

Previously a marginal force, localist groups have grown in strength after the 2014 Umbrella Movement. One notes that many localist groups have extremely young compositions. Ray Wong and Edward Leung, co-founders of localist group Hong Kong Indigenous who were both arrested by Hong Kong police and largely blamed for the riots, are respectively 22 and 24 years old. It is largely young people that the pro-unification Left is now trying paint as fascists, though this also occurred in regards to the Sunflower Movement and Umbrella Movement. One sometimes wonders why the pro-unification Left is so terrified of children and young people.

One vaguely suspects, however, that pro-unification Leftists were really just looking for an opportunity to try and trot out their usual accusations of fascism against anything which resists China. The Mong Kok riots, which were controversial for the use of violence, presented a convenient target.

Ethno-Nationalism and Anti-Leftism from Localist Tendencies in Hong Kong?

ACTUALLY IF Tan and Lee’s critique is all too typical of the pro-unification Left, it is correct to point to there being problematic elements of localism. Localism can embrace a problematic form of ethno-nationalism. Localist groups at times despise Chinese to the point of bigotry, as we see in the past year with calls for the deportation of 12-year-old Siu Yau-wai, a Chinese boy who had spent the past nine years in Hong Kong as an undocumented immigrant. Localist groups as Civic Passion and others have called vehemently for Siu’s deportation for fear that this would set a precedent for other undocumented Chinese immigrants to Hong Kong, never mind that Siu seems to have abandoned by all members of his family apart from his grandmother, and exists in an unclear legal status similar to that of a stateless person.

Along such lines, localism can embrace a form of anti-Leftism. For example, group of localist students recently elected to student council in the City University of Hong Kong has explicitly stated that they viewed their victory as a struggle between left-wing ideology and localism, and their victory as a victory for localism. We also see anti-Leftism as coming together with ethno-nationalism in Hong Kong with the frequent use of the term “leftard” to criticize those who point to discrimination against Chinese, with the view of such individuals as utopians believing in too-good-to-be-true theories of social equality who are fixated on political correctness even when this may compromise the security of Hong Kong, but also the deeper implication that such people have covert sympathies for China.

Thus, there is in fact a point to the critique of localism. However, it is a unfortunate when such critique comes from the pro-unification Left.

Image released by Passion Times, the online publication of Civic Times, criticizing leftist ideology as authoritarian in its utopianism. Photo credit: Passion Times

Image released by Passion Times, the online publication of Civic Times, criticizing leftist ideology as authoritarian in its utopianism. Photo credit: Passion Times

We might ask, why is it that there has developed a strain of anti-Leftism in Hong Kong? Namely, because of people such as Tan, Lee, and their ilk to begin with, whose Leftism is merely a disguise for a sense of nationalistic identification with China.

Chinese Cultural Nationalism Disguised as Leftism by the Pro-Unification Left

BENEATH TAN and Lee’s claim to Leftism is in reality just the sense of cultural identification with China above all else. After all, China has historically claimed to be a socialist nation and continues to do so to this day. In this way, the claim to be “Leftist” is garb for what is really just a form of Chinese cultural nationalism.

As a result, localist groups in Hong Kong associate Leftism with China and in resisting China, they see themselves as resisting Leftism. Leftists were sometimes targeted during the Umbrella Movement, even when they themselves may have been active participants in the movement, with the perception that they were spies for China or had disguised pro-China sympathies.

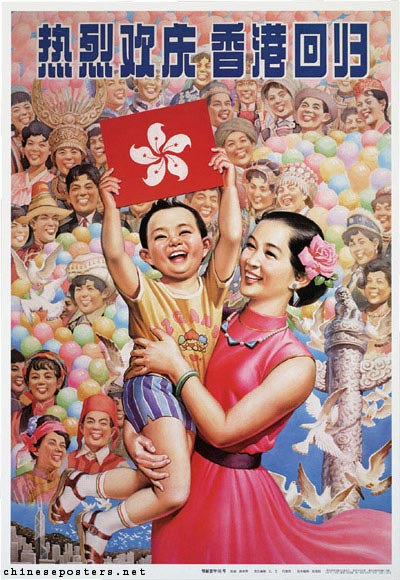

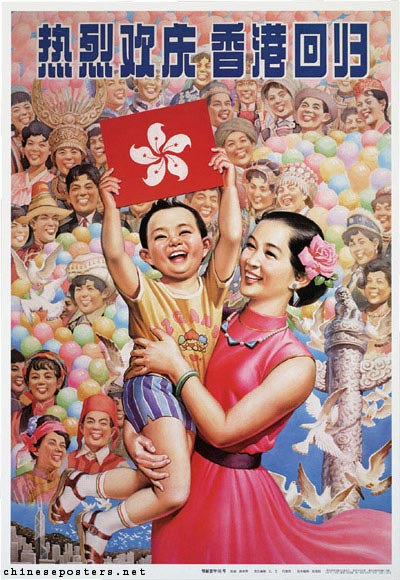

Chinese propaganda poster celebrating the return of Hong Kong to China in 1997. Photo credit: Chineseposters.net

Chinese propaganda poster celebrating the return of Hong Kong to China in 1997. Photo credit: Chineseposters.net

But we can maybe lay the blame for this at the feet of individuals as Tan and Lee and the image of Leftism they present to many in Hong Kong. We see this in how Tan, Lee, and other individuals of the pro-unification Left often attempt to deconstruct non-Chinese forms of identity in territories which China claims as part of it, in order to reestablish a sense of Chinese identity. For example, Lee in attempting to deconstruct localism or other calls for broader autonomy for Hong Kong, finds it important to insist that Hong Kong people still identify with the ethnic Chinese people (中華民族), just that they look down on mainland Chinese people (大陸人).

Lee, Tan, and others insist that China is a progressive social force because it is socialistic—or if this is a hard claim to hold up in the face of the gross capitalistic excesses of contemporary China—that China is still at least a more progressive social force than western capitalist countries. And so China must apparently be backed to the hilt. This is not at all an internationalist, leftist concern, however, but really just a form of defending the Chinese state, using the language of leftism in a way that belies ultimately Chinese nationalist concerns.

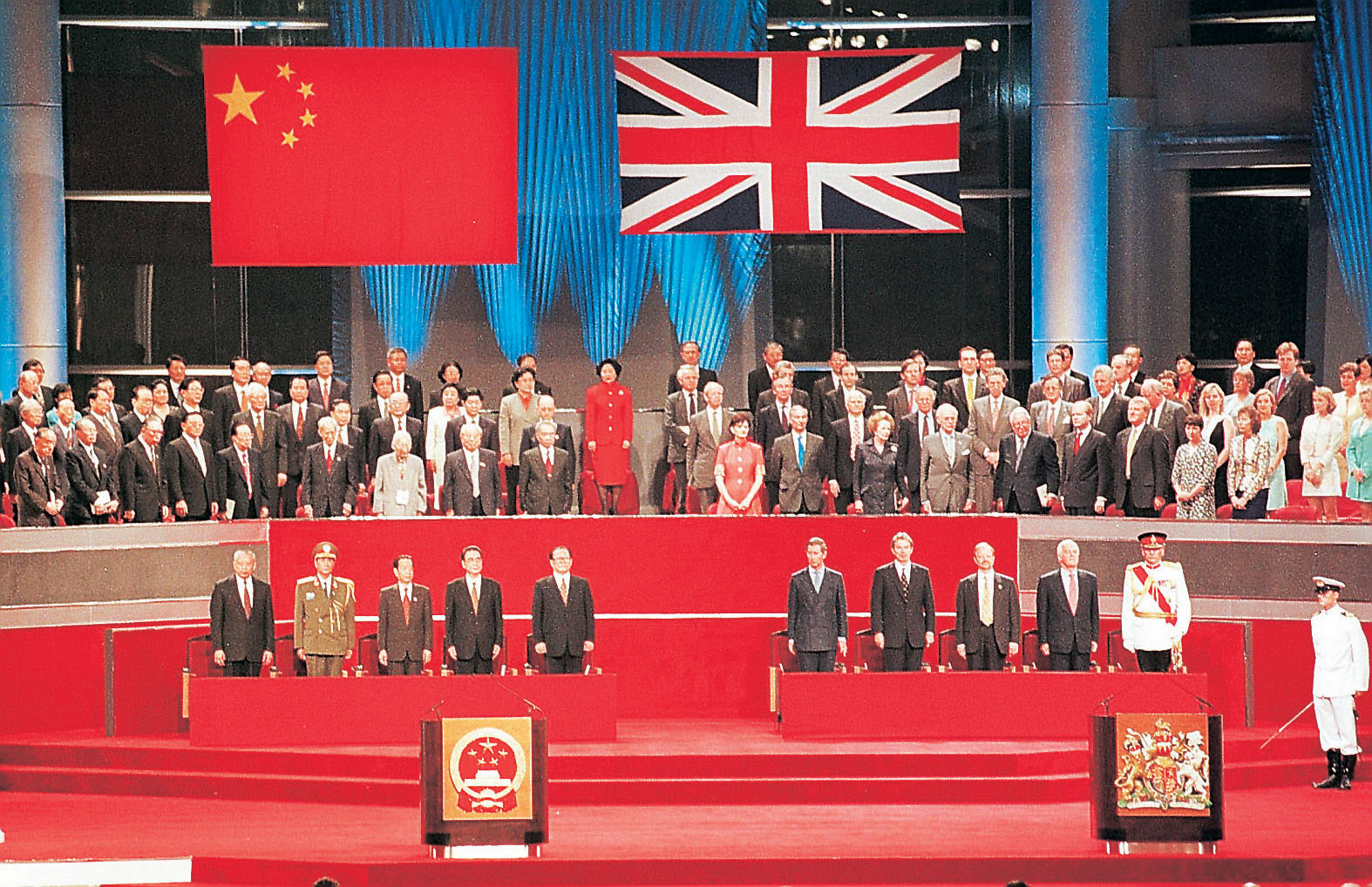

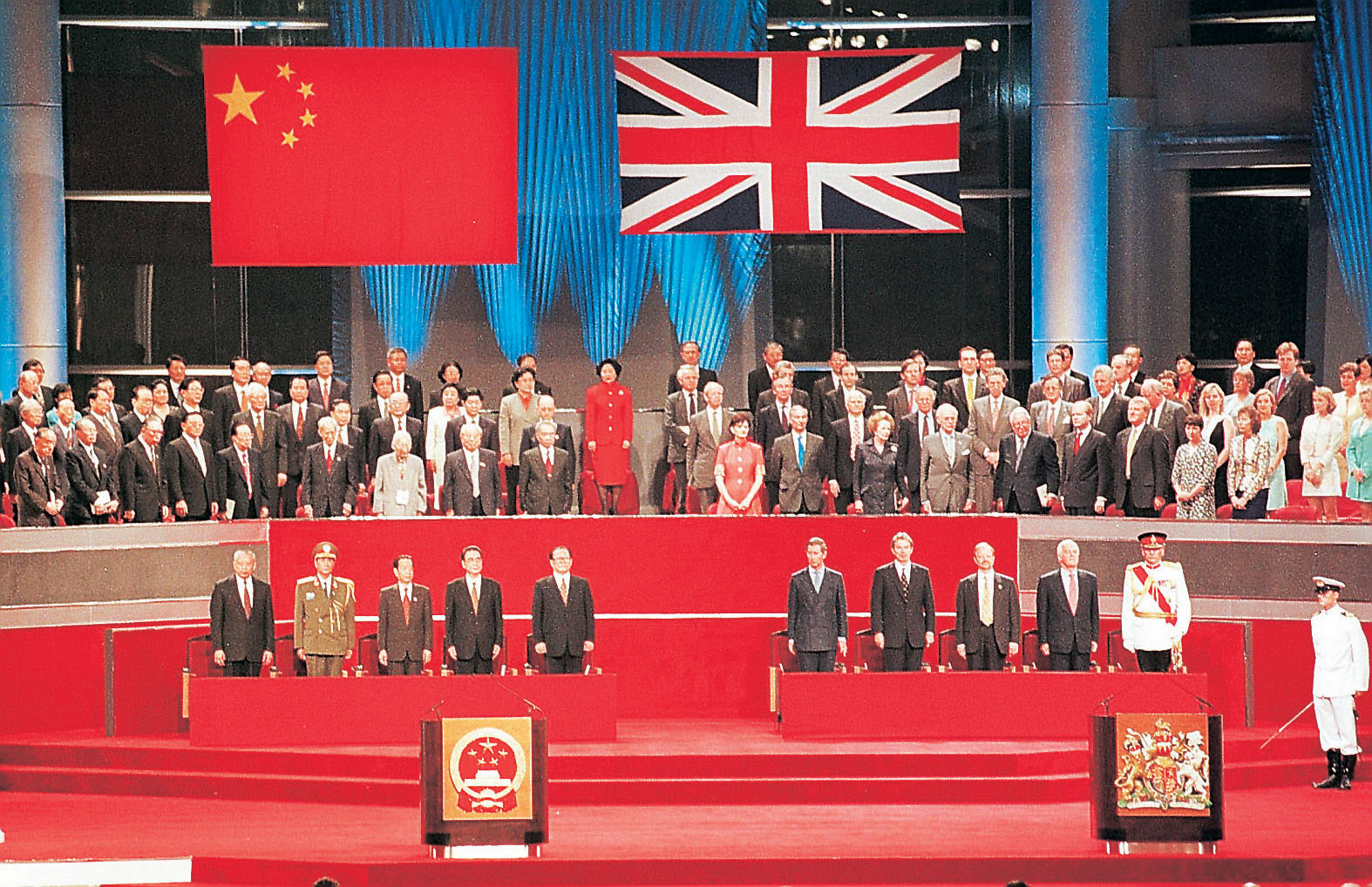

Handover ceremony of Hong Kong from British control to China in 1997

Handover ceremony of Hong Kong from British control to China in 1997

And it is unsurprising why, misled by such individuals’ depiction of leftism, localist groups in Hong Kong may have come to see leftism as the ideology of the enemy. Namely, Lee, Tan, and their ilk, have a total disinterest, even hostility, to the democratic will of the Hong Kong people. The call for democracy is attributed, for example, to simply western powers seeking to create trouble for China by implanting this idea in the minds of residents of Hong Kong or a residual colonial mindset, never mind what residents of Hong Kong themselves want.

It is funny to see self-proclaimed Leftists so utterly terrified of these social movements which are expressions of the people’s will, seeking to dismiss them as “right-wing populism” or label them dangerous as “fascism”. Funnily enough, one finds that these pro-unification Leftists have the strange but telling pattern of becoming incredibly enthusiastic about what are, in the end, populist reformist movements in the western world, but utterly hostile to Asian social movements closer to home when they may go against the interests of the Chinese state. Then, their leftism drops away in favor of Chinese nationalism, with apologism for the Chinese state taking precedence over any concerns about the will of the people.

Localism and Its Discontents

OFTENTIMES WE find that a movement, even when not directly Left or even containing a number of problematic elements, is an unfulfilled, misrecognized desire for what a Left social vision would provide answers for. The task of Leftists, then, is to try to push people towards realizing that it is in their own self-interest to embrace a Left social vision.

We can say this is perhaps true of localism. The aspirations of localism reflect the people of Hong Kong’s demand for democracy and the ability to govern their own lives, but localism misrecognizes Leftism as reflecting a hostility towards democracy, that is, as totalitarianism in the name of abstract ideals.

Moreover, in trying to draw up boundaries to shut out Chinese on ethno-nationalist ground, localism does not recognize that the interest of the people of Hong Kong in resisting the Chinese state are, in fact, shared with the Chinese people. The government of China, as the Chinese government is the enemy of the people of Hong Kong, no less than it is also the enemy of the people of China.

The Chinese government is not the Chinese people, though it may claim to act in the name of the Chinese people. The Chinese government consists of a small number of elites stifling democracy for the sake of holding onto power. Indeed, if uncontrolled Chinese immigration is causing problems in Hong Kong, we might ask why it is that Chinese people sometimes desperately seek to enter Hong Kong for the promise of a better life? Namely, because of the economic conditions which exist in China under the rule of the CPP and the social inequality it creates, even as it claims at the same time to be “socialist”.

Likewise, ethnic discrimination against Chinese actually reflects a profound sense of anxiety, rather than confidence, about one’s own identity. One must continually draw up boundaries and target an Other in order to assert one’s own identity as different, precisely because one is anxious and fearful that one’s identity may not actually be so different. Such anxieties would indicate a “negative identity,” that is, an identity founded upon only the premise of denying one is Chinese, rather than the actual assertion of an independent sense of identity.

On the other hand, a confident sense of Hong Kong identity would not be so afraid of Chinese to the point that it would seek to continually exclude Chinese. Rather, Hong Kong residents and Chinese could confidently stand together in opposing their shared enemies, without this meaning that it would negate the existence of an independent and separate Hong Kong sense of identity.

But the people of Hong Kong need better examples of Leftism than the pro-unification Left, which tends towards statism and only seeks to deconstruct Hong Kong identity in favor of a Chinese identity on grounds in the end reducible to its own cultural nationalism. It needs to proved through example that leftism is not a form of authoritarianism, even if the Chinese state cynically claims to be Left.

Precedents for Pro-Independence Leftism in Hong Kong from Taiwan?

IF ANXIETIES about localism have been raised in Hong Kong by pro-unification Leftists in Hong Kong, the anxieties of pro-unification Leftists of the Taiwanese variety have also been raised. One suspects that pro-unification Leftists in Taiwan are projecting their own anxieties about Taiwan onto Hong Kong.

After all, if we see the rise of similar social movements in recent years Hong Kong and Taiwan as the Umbrella Movement and Sunflower Movement, and similar phenomena in past election seasons with the rise of “Umbrella Soldiers” or the “Third Force”, Taiwan also went through a phase of benshengren ethno-nationalism in the past. But the Taiwanese independence movement is decades old, meaning Taiwan has had decades to meditate on questions of identity, where Hong Kong independence was until the Umbrella Movement an unheard of position.

In both Taiwan and Hong Kong, we will see as to the future of the Left. In Taiwan, certainly, we seem to have moved beyond much of the past association of Leftism with China and hostility to Leftism on the basis of that. On the contrary, with the rise of numerous self-proclaimed Left independence groups, it is now possible to push for independence as a Left position.

Similarly, though there remain right-wing nationalist groups in Taiwan, the majority position of Taiwanese civil society and activists is not marked by hostility towards Chinese along ethno-nationalist lines, regardless of the claims of the pro-unification Left that they are. On the contrary, we even saw Chinese students living in Taiwan participating in the Sunflower Movement, sometimes on Leftist grounds, and Chinese were welcomed as public speakers during the Sunflower Movement. The benshengren ethno-nationalism of the past would also seem to have been replaced by a more open sense of civic identity, given the movement’s rejection of attempts to come in with older forms of benshengren ethno-nationalism.

But this was not to deny that Taiwanese do not identify as Chinese, either; rather there was not such an overwhelming sense of anxiety about asserting one’s own identity, that one had to exclude Chinese on ethnic or other grounds. In contrast to a “negative identity” defined by opposition to another form of identity, this would be a “positive identity” and one founded upon self-confidence about own’s identity, rather than fear.

Yet if Leftism is to have a future in Hong Kong, the Left will have to take up the task of critiquing the pro-unification Leftists whose Leftism is reducible to Chinese nationalism, as well as take on the critique of localism because of misguided anti-Leftism or bigoted ethno-nationalism. In the hands of the pro-unification Left, the criticism of localism just becomes another way of reinforcing a pro-China bias, ultimately reflects a hostility towards the will of the Hong Kong people, and in that way only serves to push Hong Kong people further away from leftism.

Image released by Passion Times, the online publication of Civic Times, criticizing leftist ideology as authoritarian in its utopianism. Photo credit: Passion Times

Image released by Passion Times, the online publication of Civic Times, criticizing leftist ideology as authoritarian in its utopianism. Photo credit: Passion Times Chinese propaganda poster celebrating the return of Hong Kong to China in 1997. Photo credit: Chineseposters.net

Chinese propaganda poster celebrating the return of Hong Kong to China in 1997. Photo credit: Chineseposters.net Handover ceremony of Hong Kong from British control to China in 1997

Handover ceremony of Hong Kong from British control to China in 1997