by Brian Hioe

語言:

English

Photo Credit: 蔡英文 Tsai Ing-wen

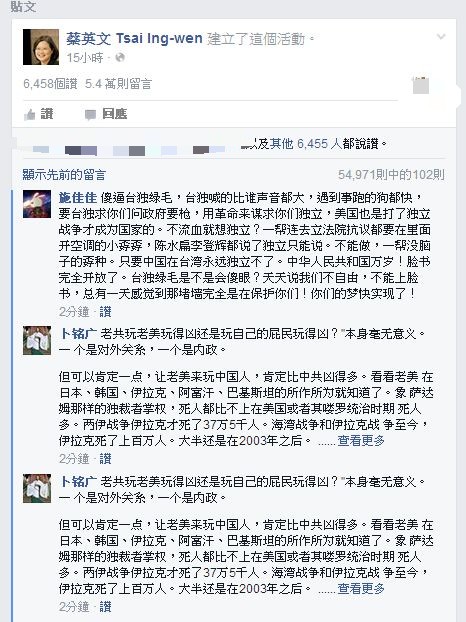

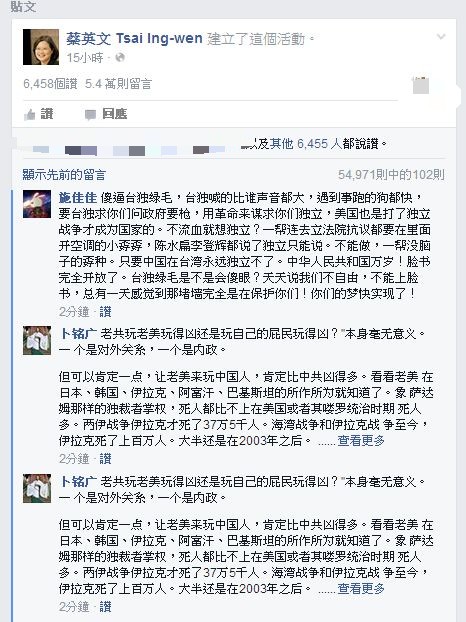

AFTER THE sudden, unexpected unblocking of Facebook in China for a day, DPP presidential candidate Tsai Ing-Wen’s Facebook page was flooded by posts attacking Tsai or claiming that Taiwan is part of China. In response, Tsai Ing-Wen released an image on her Facebook pointing to where such users were coming from and “welcoming” Chinese users to democracy.The image became widely shared by Taiwanese Facebook users, allowing the Tsai campaign to use this set of events quite skillfully in turning it into a campaign opportunity. How did the unblocking happen? It is suspected that the unblocking of Facebook was caused by an error in China’s “Great Firewall” because of the huge amount of Internet users shopping online because of November 11th being “Singles’ Day,” a holiday encouraging online shopping for single individuals unable to find partners.

The Internet trolls. Photo credit: Apple Daily

The Internet trolls. Photo credit: Apple Daily

It would seem that China’s “Fifty Cent Army” may have jumped onto the breach in the Great Firewall. The “Fifty Cent Army”, or “Fifty Cent Party”, is a term used to refer to individuals hired by the Chinese government to influence public opinion, usually by trolling targets en masse with negative comments. “Fifty cent” refers to the purported amount that members are paid per post, fifty cents RMB. Individuals employed as part of the “Fifty Cent Army” may number in the tens of thousands. If not the “Fifty Cent Army,” it may have been overly nationalistic netizens behind the posts, but many of the user accounts from which these attacks are coming appear to be bots. A war subsequently followed on Tsai Ing-Wen’s Facebook page between netizens from Taiwan’s PTT Internet forum defending Tsai and Chinese users attacking Tsai.

Mark Zuckerberg has been visibly bowing and scraping before Chinese President Xi Jinping as of late in the hopes of getting Facebook unblocked in China, in order to open the Chinese markets up to Facebook. This has included everything from placing Xi Jinping’s book, The Governance of China, prominently on his desk and publicly advising Facebook employees to read it, to marking meeting Xi Jinping as a personal milestone on his Facebook wall, and asking Xi to give his unborn baby daughter a Chinese name. The latter request, Xi turned down. Have Zuckerberg’s efforts finally paid off? That was certainly what many thought when Facebook suddenly was able to be accessed from within China, but this is probably not the case. There have been no media reports which would seem to indicate any announcement that Facebook has been unblocked in China.

More to the point, as China has developed its own rich Internet ecology, centered around Wechat, Weibo, and other platforms in the absence of Facebook and Twitter, it is to be questioned whether Facebook would have much traction in China. Wechat, for example, though a cell phone only messenger app and social network, has much more functionality than Facebook in regards to the social integration of Wechat into allowing users access to city services, store services, and other functionalities which are lacking in Facebook.

Apart from that in itself, Wechat may be ahead of the game than Facebook in regards to the integration of social media into social functions, it is also to be questioned whether Facebook as an outside social media network would be able to displace Wechat, given that Wechat’s many functionalities as integrated into daily life in China. The trade-off, of course, is that Wechat parent company Tencent works closely with the Chinese state in order to track user activities and that the integration of Wechat into society has allowed for expansive surveillance or that this may allow for social monitoring on an unprecedented scale, as we see through anxieties raised by a new credit system being introduced.

We see the sophistication of Chinese Internet censorship in that political criticism is tolerated in private circles on Wechat, with authorities only coming in when posts with political content become too widely circulated, and that politically sensitive topics are less deleted on the justification of being political criticism, but more often deleted on the basis of their being deemed to be dangerous “rumors”. But we might note that Facebook is far from blameless either in allowing for American widespread government surveillance of its users, either, as we know via Edward Snowden’s revelations about American government surveillance.

WeChat logo. Photo credit: Tencent

WeChat logo. Photo credit: Tencent

But it may be that even outside of China, or outside the use of Internet censorship in other authoritarian states, Russia being a notable example, most major political parties today worldwide with enough resources attempt to manipulate public opinion through social media networks, even in democratic countries. Within the American Democratic Party, for example, there have been recent accusations against the Hillary Clinton campaign, for example, for targeting the Bernie Sanders campaign through aggressive trolling. There have also been past accusations made against the DPP by the KMT for conducting Internet warfare against them through conducting online smear campaigns.

China’s “Fifty Cent Army” may be overkill and we see where its strategy of mass trolling often backfires, given that the attack on the Tsai campaign has probably only increased support for Tsai. Likewise, the Chinese netizen utterly absent of critical thinking skills who believes each and every word of the “Fifty Cent Army” is few and far between. One suspects that, where the “Fifty Cent Army” aims to influence public opinion through brute force, more subtle strategies aimed at influencing public opinion would be more effective.

China and Taiwan are both societies in which the role of the Internet and social media has been very visible in recent years. We saw the role of social media in mobilizing activists during the Sunflower Movement quite visibly by way of Facebook and PTT. And if Internet censorship and authoritarian restrictions on protest in China have not allowed for anything like social media facilitating the outbreak of social movements, we see phenomena in which netizens become a force to call for popular justice, as in the “human flesh search engine” (人肉搜索).

Such phenomena is not particular to Taiwan or China, either, as we see with netizen activism coming from the Reddit in the Anglophone world, or with Anonymous and its many international split-offs being an international example. With such examples, we might also point to where populist netizen activism becomes mob rule, when netizens begin to target individuals to the point of harassment, or when netizens target the wrong individuals.

However, if Taiwan is quite a particular example, we may be seeing something of the future of politics here. Taiwan in fact has the highest Facebook penetration in the world with 65% penetration. It seems to be a rather unique phenomenon where, for example, in the Taiwanese activist world it is that there are a number of individuals who have risen to the status of being “Internet celebrities” as well-known activists or become known as public intellectuals through essays which circulate on social media.

And if the attacks on Tsai Ing-Wen’s Facebook was countered by Tsai skillfully, Tsai’s campaign has generally been to date quite skilled in influencing public opinion, often through the creation of images which become widely circulated on social media. A recent example would be her criticisms of Xi-Ma summit in Singapore this past weekend by way of an image posted on Facebook which went viral—certainly a subtle but effective way of influencing public opinion in contrast to where the onslaught of attacks on Tsai are ineffective because of their brute force nature.

In this sense, we may be that cyberspace is a domain by which many of the future battles of politics will be fought and a heated terrain of political contestations. What if, for example, Facebook did become permanently accessible in China and Tsai had to deal with continual attacks from the “Fifty Cent Army”? Tsai would have to find some way to cope, either through mobilizing her own Internet forces. Or Facebook itself would have to step in in some way curb the actions of the “Fifty Cent Army”—something of which it is questionable Zuckerberg would want to do. But this may just be further reflective of the nature of the Internet as a politicized space in the present.

The Internet trolls. Photo credit: Apple Daily

The Internet trolls. Photo credit: Apple Daily WeChat logo. Photo credit: Tencent

WeChat logo. Photo credit: Tencent