The New Power Party, The Rise of Political “Amateurs,” and the Third Wave of Civil Society Candidates After the Sunflower Movement

by Brian Hioe

語言:

English

Photo Credit: 鄭景雯/CNA

TAIWAN MUST SURELY be the only country in the world in which the country’s foremost heavy metal musician declares his entrance into electoral politics and does not turn the event into a publicity stunt but does so, in fact, as a serious development in electoral politics. That on February 21, Chthonic frontman and longtime Taiwanese independence activist, Freddy Lim, declared his intent to run for legislator of his native Daan district in 2016 has been the latest development in Taiwanese electoral politics as we approach 2016 legislative and presidential elections. Lim plans on running as a candidate of the New Power Party, which was founded in late January. But more broadly, we can point to Lim’s candidacy as one of a series of developments which occur in the aftermath of the Sunflower Movement and the victory of Ko Wen-Je during nine-in-one elections of November of last year.

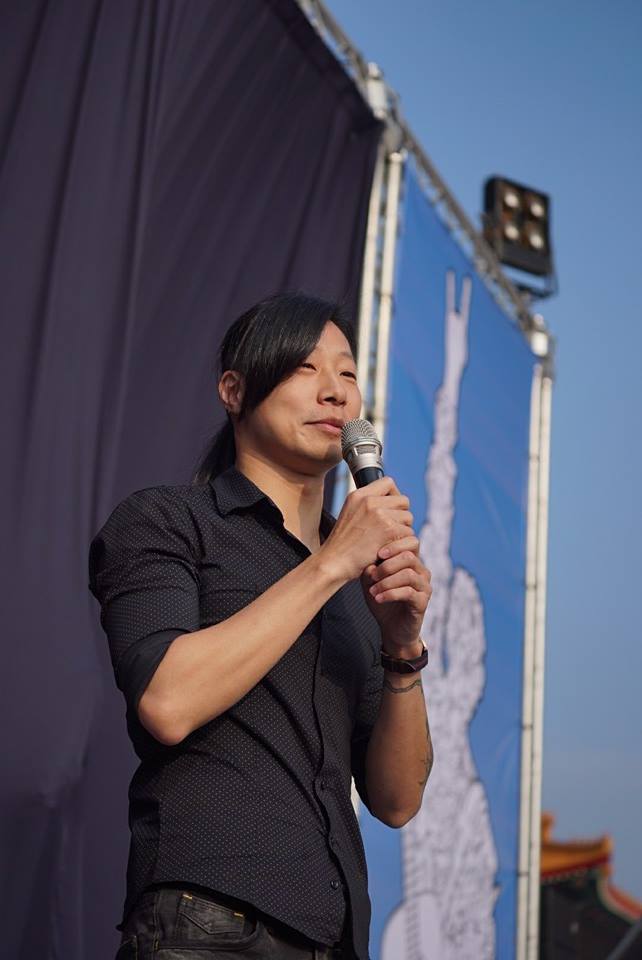

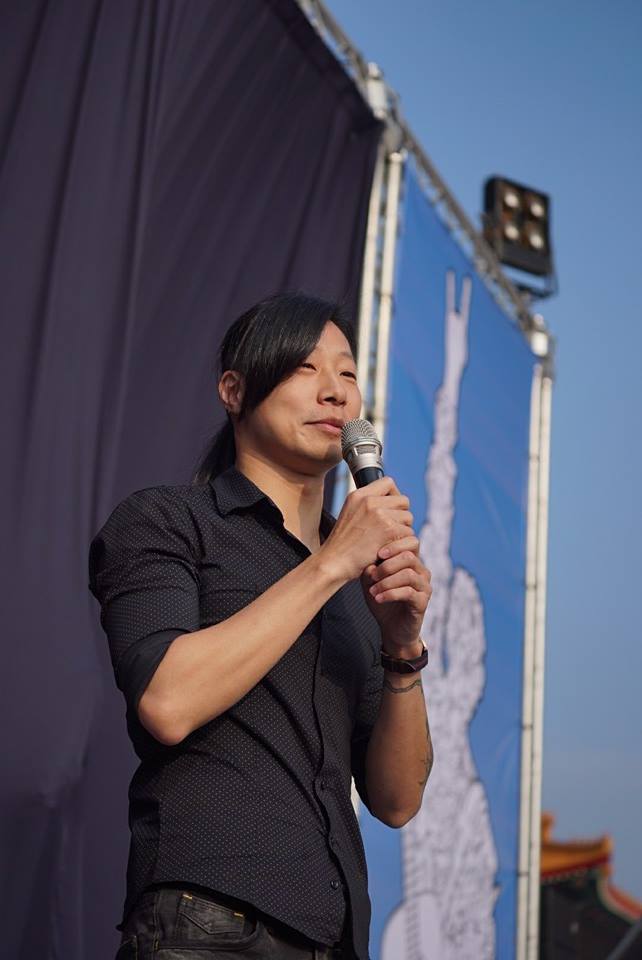

Lim speaking at Gongsheng Music Festival on 228 of this year. Photo credit: 共生音樂節

Lim speaking at Gongsheng Music Festival on 228 of this year. Photo credit: 共生音樂節

Lim’s candidacy as a member of the New Power Party has drawn most of media attention to date. During the same period of time that Lim declared his candidacy, Taiwan also saw the launching of the Social Democratic Party. Founding members (in which the most famed member of the Social Democratic Party is Fan Yun, a professor at National Taiwan University), cited the need for Taiwan to have a political platform form for the advocacy of Social Democracy, in consideration of that the organized development of political Left in Taiwan has been long said to be impossible on the basis of Taiwan’s history of Martial Law and state-mandated anti-communism. But in consideration of that there is a longstanding discourse in Taiwan which looks to the social democratic political parties of Europe for inspiration, particularly in Scandinavian countries. It seems very probable that the Social Democratic Party in Taiwan will tend towards Left politics on the basis of the political imaginary of the European social democratic ideal, which is understood as representing the quintessential exemplar for a global Left.

Though it has been noted that Lim’s candidacy and the formation of the Social Democratic Party are concurrent development, to date in English-language media about Taiwan, less focus has been placed on that Lim’s New Power Party and the Social Democratic Party are both split-offs from the Taiwan Citizen Union (TCU). TCU was formed by former DPP chairman Lin Yi-Hsiung in July of the past year, with the intent of establishing a third force outside the DPP that would be able to challenge the DPP within the rubric of the pan-Green alliance. Though the future of the Taiwan Citizen Union is now in question, we can trace the origins of both parties within the developments of Taiwanese civil society politics from 2013 to the 2014 Sunflower Movement up until the present.

Fragmentation within the Taiwan Citizen Union

CONCERNING THE origins of the New Power Party, we can account its beginnings to the 2013 protests against the killing of army corporal Hung Chun-Hsiu at the hands of his superiors and the subsequent covering up of the event. Summer of 2013 saw over 100,000 take the streets of Taipei in August in an expectedly large set of protests in outrage over the cover up after a period of political ennui following the rise of Ma Ying-Jeou as president and the fall of former president Chen Shui-Bian. No doubt, in retrospect, we can see the seeds of the Sunflower Movement in these protests, so far as the Sunflower Movement grew out of the two year development of young people’s participation activist politics around issues as land evictions in Miaoli, and Gongliao nuclear reactor #4. But where the participation of young people in these two issues was largely driven by social media based activism, the 2013 protests pioneered this phenomenon so far as the Citizen 1985 group which was the main organizer of protests began through commentators on the PTT Internet forum which is ubiquitously used in Taiwan.

Citizen 1985 would be increasingly consigned to irrelevance in later times, owing to controversy regarding the apparent obsession of Citizen 1985 organizers with keeping orderly conduct during protests, so as to tone down controversy, and organizers’ general pedantry. Citizen 1985 was overshadowed entirely during the Sunflower Movement, and has become nearly forgotten about in the present.

Protest in August 2013. The logo on the placards held by protestors would become iconic of Citizen 1985. Photo credit: CFP

Protest in August 2013. The logo on the placards held by protestors would become iconic of Citizen 1985. Photo credit: CFP

But key members of the New Power Party first came to prominence during the 2013 Hung Chun-Hsiu protests. Apart from Freddy Lim, the most prominently featured candidate of the New Power Party is Hung Tzu-Yung, the sister of Hung Chun-Chiu, who came to prominence in the protests about her brother’s death. Hung will be running for office in Taichung district and her candidacy as a New Power party candidate comes after rumors of her plans to run for political office and some speculation that she would run as a DPP candidate. But where other prominent New Power Party candidates are Hu Yen-Po and Chiu Hsien-Chih, lawyers during the Hung Chun-Hsiu case, we can more broadly point to the roots of the New Power Party in the Hung Chun-Hsiu incident.

We can further point to shared roots regarding the New Power Party and Social Democratic Party alike in the Taiwan Citizen Union and the series of political developments following the Sunflower Movement. For example, the New Power Party would appear to be rather close to Academica Sinica researcher Huang Kuo-Chang, who was one of the “triumvirate” of Lin Fei-Fan, Chen Wei-Ting, and himself as leaders during the Sunflower Movement, even as he saw less media limelight in comparison to student leaders Lin and Chen. Huang was present during the press conference in which Hung declared her candidacy for Taichung district legislator. However, where the most prominent candidate of the Social Democratic Party, Fan Yun, was also among the founders of the Taiwan Citizen Union, so, too, was Huang—as well as Freddy Lim himself. Therefore, both parties have shared roots, largely drawing upon the same pool of prominent Taiwanese activists.

We can perhaps speculate as to the internal tension within the Taiwan Citizen Union which led to true formation of the New Power Party and Social Democratic Party as splits. But, on the other hand, while the New Power Party and Social Democratic Party are distinctively separate parties, they may act as as part of a coalition “third force” against the DPP and KMT.

Three Waves of Civil Society Developments

IN BROADER VIEW of the developments in Taiwanese electoral politics in the past year, the formation of the New Power Party and Social Democratic Party is the “third wave” of a series of events in which new groups and individuals make their appearance on the Taiwanese political stage.

In the “first wave” in late August and early Fall, we saw the formation of the Tree Party, Formoshock Society, Youth Occupy Politics, and the renewal of the Taiwanese Green Party. Some of these groups had ties to the Taiwan Solidarity Union and other groups were split-offs from previously existing groups. Formoshock Society, for example, was formed by Sunflower Movement leaders that split off from the leadership of Lin Fei-Fan and Chen Wei-Ting out of disagreements during the heat of the movement. The Tree Party was a split-off from the Green Party by former Green Party Taiwan secretary Pan Han-Shen, it seems constituted originally of individuals who had a hand in maintaining the Songshan occupation in Taipei during August 2014 out of opposition to the illegal cutting down of trees by Farglory Construction in order to build Taipei Dome.

The “second wave” followed the victory of Ko Wen-Je in his battle against Sean Lien for mayorship of Taipei in 2014. Where Ko was a political amateur, he saw victory with the support of Taiwanese civil society—triumphing over the KMT political apparatus whose political and economic support of Sean Lien seemed to make Lien’s victory all but certain. Ko’s victory was inspirational, leading individuals as Sunflower student leader Chen Wei-Ting to run for legislator of his native Miaoli through by-election. Chen, of course, later withdrew as a result of a scandal regarding past sexual harassment. But during the time he ran for office, Wuerkaixi, former student leader himself during the 1989 Chinese Tiananmen Square student movement, and a resident of Taiwan for the last 18 years, announced his candidacy for legislator of Taichung district, also on by-election. In an interview with the Wall Street Journal regarding his run, Wuerkaixi cited recent student activism and Ko Wen-Je’s victory as inspiring him. Wuerkaixi later declared that he would be withdrawing with plans to run in 2016 instead, although it remains to be seen whether he would follow through.

Yet with this “second wave” of political amateurs running for office, we can point to how the Ko victory inspired candidates with a background in Taiwanese civil society, but no political experience, to run for office. Again, before running for mayor of Taipei, certainly one of the nation’s most important political positions, Ko had no political experience.

Certainly, where its twenty five years of political democracy since the end of the authoritarian period are concerned, Taiwan has had a tradition of individuals with no experience in political office. Before becoming mayor of Taipei in 2002, for example, current Taiwanese President Ma Ying-Jeou never held political office, although serving in various official positions as part of the KMT. Sean Lien, who ran for mayorship of Taipei in 2014 nine-in-one elections, as a KMT candidate and the latest scion of the Lien family of the “Four Families of the KMT”, also previously had no political experience before running.

But where most political “amateurs” that have run for public office in Taiwan have been KMT candidates, in effect “created” and funded as politicians by the KMT political apparatus, since the end of the Sunflower Movement we have seen a number of individuals with backgrounds in activism and not traditional politics run for office. As critics have, it bears pointing out in the “third wave”—that of the rise of the New Power Party and Social Democratic Party—neither Freddy Lim nor Hung Tzu-Yung have any political experience in office. This may mark a new phenomenon within Taiwanese progressive politics—the rise of the political “amateur”.

A “United Front” Against Both DPP and KMT?

IT MAY BE of interest to note that both DPP and KMT alike have been forced to the acknowledge that third parties are now a significant force in Taiwanese politics. Where the Sunflower Movement saw significant backlash against a DPP which was seen as attempting to co-opt the movement and the development of third parties afterwards largely grew out of Taiwanese civil society’s distrust of the DPP—as well as a desire to push against the DPP.

And, in fact, the DPP has acknowledged the importance of those third parties which have grown out of civil society. Tsai Ing-Wen, who has declared her candidacy for nomination as DPP candidate 2016 presidential elections, has expressed her willingness to work with third parties that have grown out of civil society groups. It generally seems unlikely that new civil society groups will break from the DPP altogether, but more generally operate within the rubric of pan-Green politics. But even the KMT has acknowledged the importance of new third parties birthed from civil society groups, so far as the KMT has taken various steps to appeal to the young by hosting youth training camps in past months, and attempted to play up support of it by civil society groups—although, of course, these are often shell groups intended to give the KMT the appearance of popular support but actually backed by the KMT apparatus.

Tsai Ing-Wen announcing her intent to compete for DPP nomination as a presidential candidate in 2016. Photo credit: CNA

Tsai Ing-Wen announcing her intent to compete for DPP nomination as a presidential candidate in 2016. Photo credit: CNA

However, some commentators have, in fact pointed to the dangers of a plurality of third parties coming to exist in Taiwan outside of the DPP. Namely, what they point to is that the power of the KMT political apparatus is not yet broken and that there being “too many” third parties in Taiwan may just split the vote—leading to a KMT victory. Where supporting the DPP, even in spite of the fact the DPP has in recent years drifted towards a more conservative political bent, is simply the safer bet.

Indeed, where the recent outgrowth of political parties is concerned, this may be true. In examination of the three waves of new political parties and candidates entering electoral politics after the Sunflower Movement, we can point to these different waves are not, in fact, just the product of successive periods of activity by Taiwanese civil society. Rather, as in the example of the fragmentation of the Taiwan Citizen Union in the “third wave”, and the formation of groups out of fragmentation date back to the Sunflower Movement in the “first wave”, at least part of these different waves of activity are the product of internal splits among civil society. But does that leave us with no other option than to vote DPP, for fear of the KMT winning because of a split vote?

Perhaps what is needed in Taiwanese civil society is something of a “united front.” Political parties originating from within Taiwanese civil society need to remain be able to form a coherent “third force” that can challenge DPP and KMT alike. This “united front” may be able to offer a variety of political tendencies within it, in order to represent different political ideologies and the differences of opinion that exist within Taiwanese progressive. But when needed, civil society needs to remain unified in order to resist both the KMT and the DPP, so far as the DPP can prove political conservative and it remains necessary to push against it from the outside.

It will not do to simply to simply suggest that anything outside of the DPP is dangerous, that the only option whatsoever is to back the DPP. Rather, what Taiwanese civil society needs to develop is the capacity to have productive disagreements, in which a variety of different political tendencies can coexist within a unified front in order to oppose the larger, entrenched political forces of Taiwan. This way, the specter of the KMT does not become something held up by the DPP to simply threaten the Taiwanese civil society and to submitting to its rule. We shall see if Taiwanese civil society is able to develop that capacity in the coming elections.