by Brian Hioe

語言:

English

Photo credit: Enbion Micah Aan

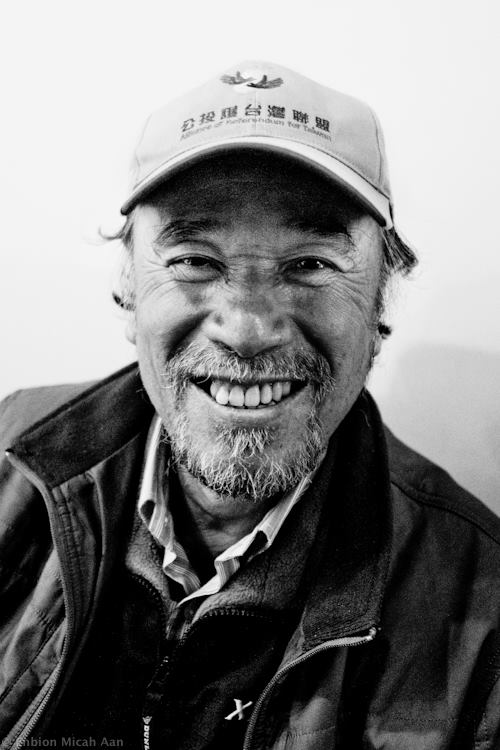

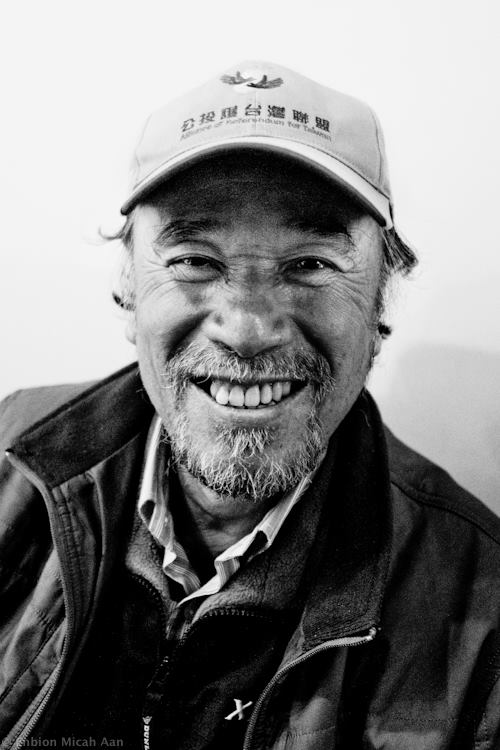

Tsay Ting-Kuei (蔡丁貴) is a longtime Taiwanese independence activist, dating back to the Martial Law period, during which he was blacklisted from returning to Taiwan because of his political activities abroad while studying in America. As a result, he was only allowed to return to Taiwan after the end of martial law.

In 2008, Dr. Tsay led the Taiwan Association of University Professors on a hunger strike for referendum reform, and as chairman of the Alliance of Referendum for Taiwan, he has continued activism on behalf of the cause of Taiwanese independence. AORFT actions have included an occupation outside of the Legislative Yuan which has lasted for over 2000 days, toppling the statue of Sun Yat-Sen in Tang De-jhang Memorial Park in Tainan in February 2014, and participation in the Sunflower Movement. He teaches at National Taiwan University.

On December 17th, 2014, New Bloom’s Brian Hioe sat down with Dr. Tsay in New York City, for an extended interview.

Background

Brian Hioe: My first question is regarding the Alliance of Referendum for Taiwan (AORFT). For a foreign reader who isn’t familiar with AORFT and doesn’t know what you would do, how would you explain AORFT and the work you do?

Tsay Ting-Kuei: AORFT began in 2008. At that I was chairman of the Taiwan Association of University Professors. Ma Ying-Jeou became president that year as well. During the election, he said that for Taiwan’s future, it would be Taiwan’s 23,000,000 that would have to decide its future. But once he became president, he allowed Chinese officials to come to Taiwan, as though he had changed his mind and began to accept the claim that mainland China should have a say in Taiwan’s future.

Tsay Ting-Kuei. Photo credit: Enbion Micah Aan

Tsay Ting-Kuei. Photo credit: Enbion Micah Aan

I felt Ma Ying-Jeou had gone back on his stated policy, but society didn’t seem to realize how serious the problem was. This was the first time since the KMT fled to Taiwan from China that Chinese officials were allowed to come to Taiwan. I thought this was Ma Ying-Jeou’s attempt to make the international world think as though Taiwan had already become part of China, through United Front methods.

At that point in time, I was chairman of the Taiwan Association of University Professors. So I wanted to participate in an event with the DPP. DPP events usually end at 9 PM, but we wanted the event to be more visible and more intense. Once the event ended, I began a hunger strike because society didn’t seem to be paying attention to this issue.

After the hunger strike, a lot of groups wanted to participate in further actions, AORFT came out of that. Our slogan is “Return people power to the people”. The hope was that if Ma Ying-Jeou wanted to carry out exchanges with China, he shouldn’t decide on his own, people should express their will on whether do it. But after AORFT was formed, the question was how people should express their will. One was voting through public referendum, the second was through the Legislative Yuan. Both were methods blocked by the Chinese KMT, as the largest party in the country. We believed this was an indicator that Taiwanese society was very unequal and that this was not right. So we came up with two demands, one was overturn the so-called Birdcage Referendum Act. The second was to change the system of legislative elections.

After Chen Yunlin came to Taiwan, during the time of Wild Strawberries, the important demand of the Wild Strawberries was to resist the visit and oppose the Parade and Assembly Law. But it only lasted for two or three months, then they went back to their schools. We took their demands and incorporated it into our platform. These became the three important demands of AORFT, the first two I mentioned, plus repeal of the Parade and Assembly Law.

We continued to protest, but the government didn’t pay any attention to us. We understood much better as time went on what kind of government the KMT represented in Taiwanese history. Part of Taiwanese history I had come to know from when I studied abroad in America, but more or less, the view then was that though the KMT had come to Taiwan for so long, so there was possibility of the KMT reforming in reaction to people. But after this protest, with no reaction, we began to change viewpoints. From our view, if these demands were met, the Chinese KMT would be affected a great deal and so it wouldn’t agree or allow this. Our view, of course, was that the Republic of China was something that had fled from China to Taiwan as a government-in-exile. Taiwanese people were not included in the government it had erected, and colonialist methods of control were used to control the people. So the aim of our protests became to overturn the Republic of China government-in-exile and the colonial system it had erected.

From history, we hope Taiwanese people, along with other colonies formed after the Second World War, have the ability to determine their future through referendum. This would allow us to decide the future course of Taiwan. This would be the independence of the Taiwanese people and annulling of colonialism through referendum.

There are some secondary demands as well, for example, in the case of Chen Shui-Bian. With Chen, we believe his jailing is political retribution, under this system this is an authoritarian measure. So we want to overturn authoritarianism in Taiwan as well. The media has generally been controlled by the KMT, and now we can see control from the Chinese Communist Party as well, through economic means. We believe these are important issues to the establishment of Taiwanese democracy.

BH: Can you discuss the activities and actions you do? The most apparent is, of course, the occupation outside of the Legislative Yuan that AORFT has done for over one thousand days.

TTK: Our main form of action is when Ma Ying-Jeou attempts to carry out irrational policies, to react and respond. To be able to respond at any time. If there’s no response, after all, the Ma government would take it as a sign to continue pushing. The most important actions to respond to are, of course, the ones concerning China. For these few years, there are two things we can talk about. One is because Ma continues to allow Chinese officials to officially visit Taiwan, so one is we need to respond to that. Because it’s a means for China to examine Taiwan. The other is, again, to understand the conditions of Chen Shui-Bian’s imprisonment.

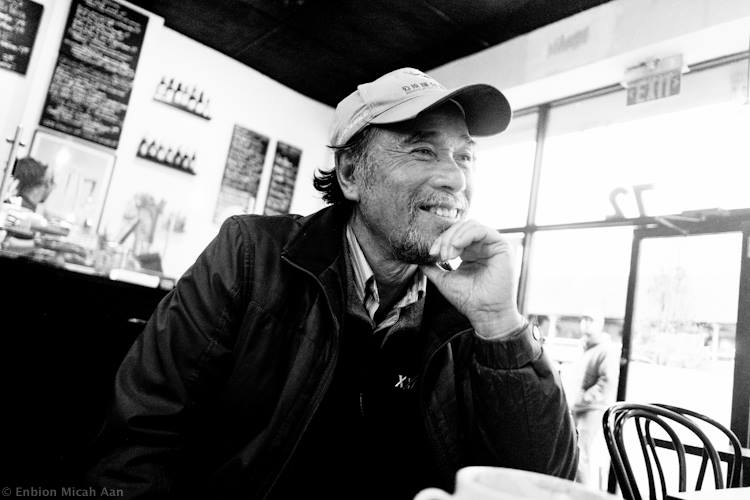

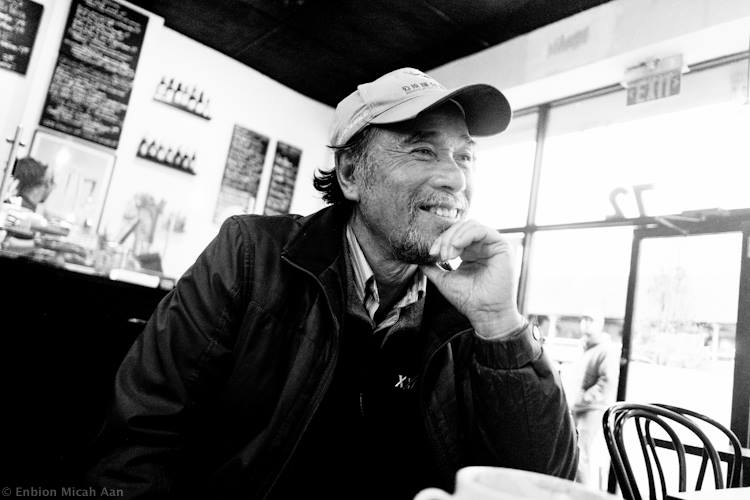

Tsay Ting-Kuei (left) and Brian Hioe (right) on December 17th, 2014. Photo credit: Enbion Micah Aan

Tsay Ting-Kuei (left) and Brian Hioe (right) on December 17th, 2014. Photo credit: Enbion Micah Aan

As for means, we promote non-violent protest and the values behind non-violent protest. We also make attempts to support oppressed peoples, as Taiwanese indigenous peoples, workers, etc. Anyone who is oppressed, so long as it’s part of a larger, public issue, we will support them from the background.

But because we’re a pro-independence group, sometimes people don’t want us to support them! In Taiwan there’s a problem, where sometimes with social issues, they don’t want any connection to politics. They think we’re too political because of our pro-independence stance. Our view is Taiwan’s problems are all political problems. It is political problems which give rise to inequality, or unfair policies. A lot of people don’t understand, they think cutting off social issues from politics accomplishes more.

The Meaning of Taiwanese Independence

BH: Can I ask about how you view the issue of Taiwanese independence? How would you explain the history of Taiwanese independence?

TTK: In regards to the issue of Taiwanese independence, first, I think there are a lot of people who are unclear about what that means. Some people think it means independence from China. That’s not correct. Because of the defeat of China by the Japanese in 1895, Taiwan became a Japanese colony and was split off from China at that point in time. But because some people’s ancestors came from China, the effect is that they believe that Taiwanese independence means independence from China. It becomes a largely confused matter.

After the KMT came from China and instituted martial law until 1987, for 38 years, the control of the KMT has led to a lot of laws and policies not being changed from how they were when they were brought over from the mainland. Including the Constitution of the Republic of China, which, after all, includes Mongolia and other now independent countries in its territory. So my view is if we really understand the meaning of Taiwanese independence, it is to put an end to the undemocratic rule of the Constitution of the Republic of China. This is what I view as the real meaning of Taiwanese independence. Taiwanese people shouldn’t need to suffer the control of the “Republic of China”, which is the means by which colonial rule is instituted. This isn’t independence from China, per se.

BH: So you would say it’s related to democratization.

TTK: Yes. Of course. Democratization is what is required to overturn the government-in-exile of the KMT. It’s for that reason why in 1979, why there would be the Kaohsiung Incident, and why the Parade and Assembly Law was instituted to restrict social gatherings. In 1990, there was the Wild Lily Movement which pushed for direct election of the president. As such, there could be the transfer of power in which the DPP took the presidency in 2000. There were successful results up until 2008, when the KMT took power again, which was a failure.

During the interview. Photo credit: Enbion Micah Aan

During the interview. Photo credit: Enbion Micah Aan

I think the DPP missed the key point when it took power in 2000 because the system was irrational, but the DPP defended the system once it took power, and did not change some of what was irrational. The people who supported the Republic of China have a lot of power because of KMT party resources to begin with, so it’s not easy to change. But the important point was not grasped, so it became that until today, from Ma Ying-Jeou’s presidency, he’s continued to advance policies.

Up until this year, it seems every ten years or so there’s a large incident in Taiwan. In 1979, that was the Kaohsiung Incident. 1990, the Wild Lilies. 2000, with the rise of the DPP. Then 2014 with the Sunflower Movement. In between, there are small movements. With 2014, students came out in opposition to the CSSTA. Behind the CSSTA was to resist control of Taiwan by China, because the CSSTA would have increased China’s economic strength in China.

Taiwanese Independence in the Sunflower Movement

BH: I want to ask about the relation of the Sunflower Movement and Taiwanese independence. At least from my own point of the view, before two years ago, not a lot of Taiwanese young people paid attention to issues of Taiwanese independence. It was with increasing attention paid by Taiwanese young people to social issues as the anti-nuclear movement or what land issues in Miaoli, young people began to pay attention to the issue of Taiwanese independence.

But in the Sunflower Movement itself, it strikes me that a lot of the key figures, including leaders, are in support of Taiwanese independence but weren’t willing to say so very clearly. It was still too controversial a view, so it was closeted during the movement. Do you have any thoughts on this?

TTK: Actually, I think that before the movement, it was that young people didn’t know very much about or did not pay very much attention to Taiwanese independence. Like I said, a lot of people thought that Taiwanese independence meant independence from China for a long period of time. In the actuality of reality, of course, they know that Taiwan isn’t controlled by China right now. So they think there’s no need for such a thing. That Taiwan’s problems of democracy come from the control of the Republic of China government-in-exile isn’t particularly visible.

Photo credit: Enbion Micah Aan

Photo credit: Enbion Micah Aan

Before the student movement, in regards to groups like ours, young people didn’t know what Taiwanese independence meant exactly. They thought we were past our expiration date, I guess you could say. But when the issue of the CSSTA became a big thing, it became more clear that there were issues they couldn’t decide on. So it provoked deeper reflection, I think.

BH: After the Sunflower Movement, some groups have appeared saying that the KMT should be eliminated. Regarding Taiwanese democratization, you think they’re different from previously existing groups in Taiwanese civil society, even if they don’t say Taiwanese independence directly either?

TTK: For me, I would regard the Sunflower Movement as an advance in Taiwanese democratization, which is why I went over Taiwanese history in regards to the cycle of events which happened every ten years. The loss of power of the DPP was a blow to democratization, but current events have allowed for progress again.

Maybe the phrase Taiwanese independence is not used by participants, but they believe social issues are something that the people need to decide. I think this is a good foundation. After the Sunflower Movement, with the student groups that have emerged, we can largely divide them into two groups.

One side looks at things more similar to how I do, which is to say, that we view Taiwan’s problems are because of the Chinese KMT’s influence and the constitutional system it has set up. As a result, we advocate finding ways to get rid of the current constitution set up by the KMT.

Other student groups think that the constitution can be amended, and that this will address Taiwan’s problems. For example, Taiwan March, they push for a lowering of the threshold for referendum from 50% to a lower percentage. It makes it much easier to pass a referendum, of course. But what they worry about as well is that if the referendum threshold is too easy, the referendum passes too easily, and that’s also no good. They hope to find a middle point in the middle. This is their demand.

I believe that their overall demand won’t be accepted by the KMT. On the side of the DPP, there’s no problem. The path these young people are following is about the same as the path I walked when I was young. Everyone first wants to use methods that reform a bad thing. But in the end you discover there seems to be no ability to change it. Talk with them and they don’t change. In the end, you decide you need to get rid of the system as a whole. From my view, this is a natural process. When you encounter heavy difficulties, you realize if you talk with them, they don’t change.

BH: Do you think they need to take more aggressive tactics? For example, as in AORFT occupying outside the Legislative Yuan or pulling down the Sun Yat-Sen statue in Tainan.

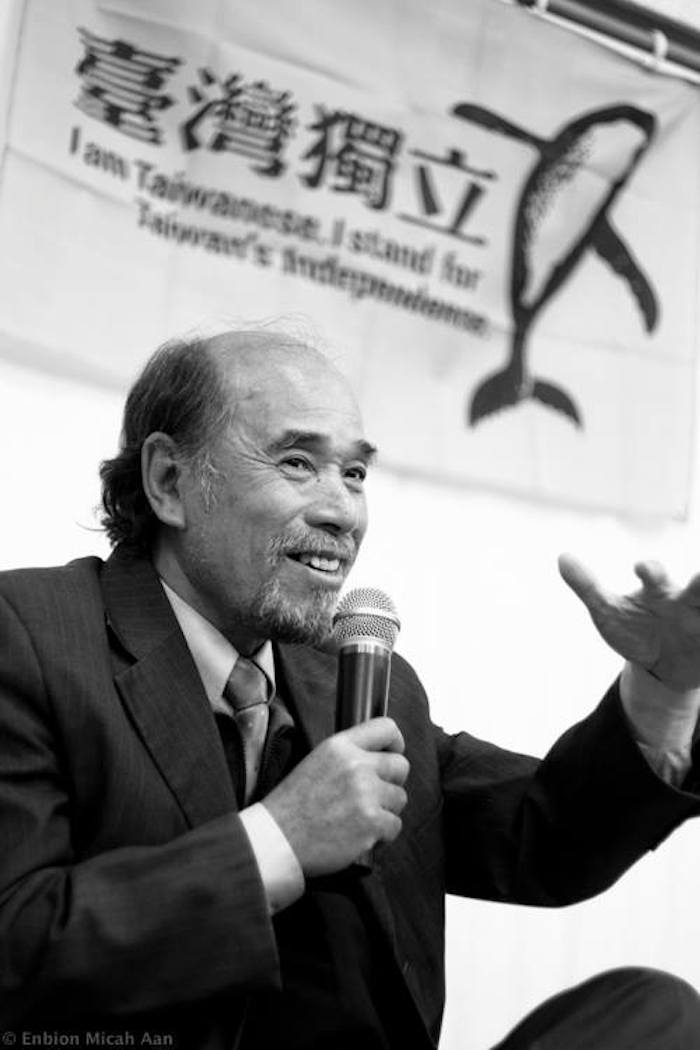

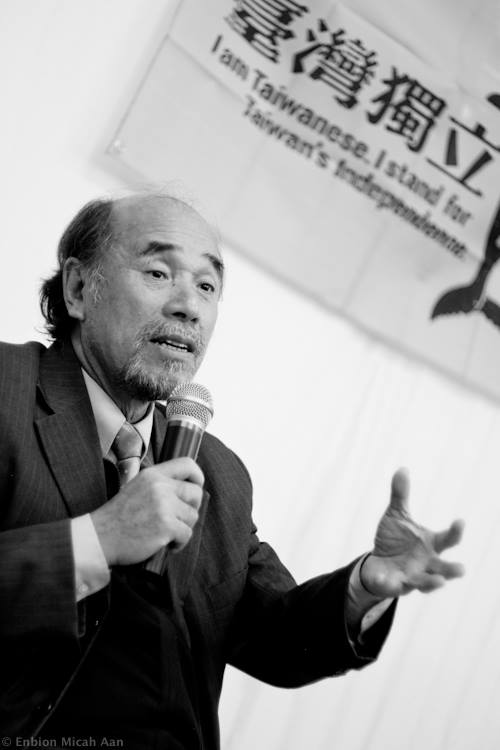

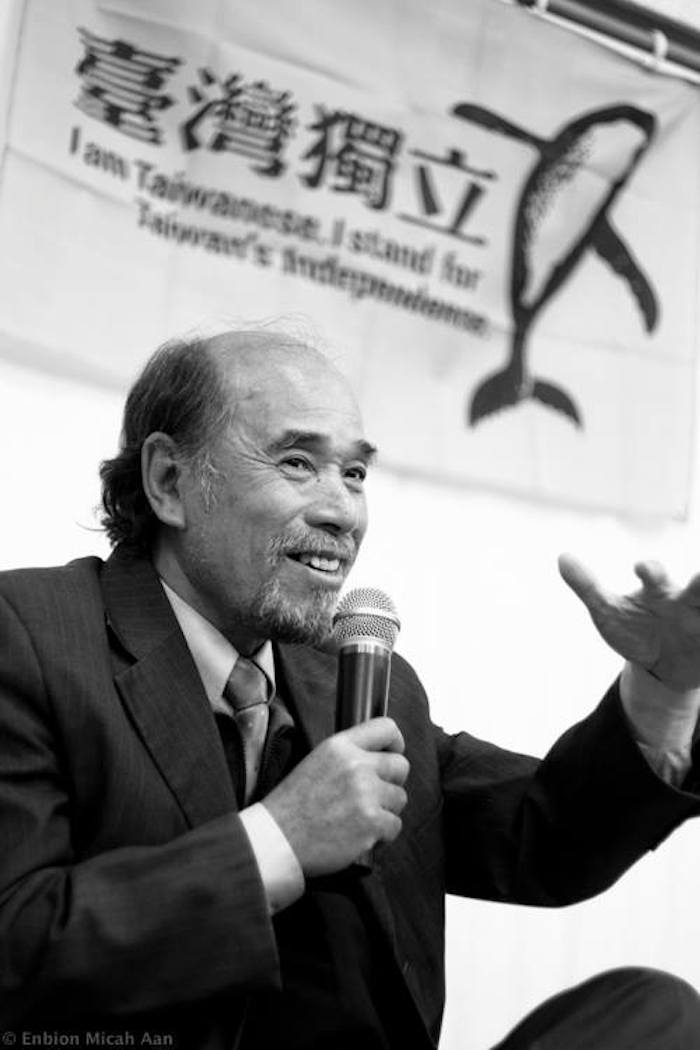

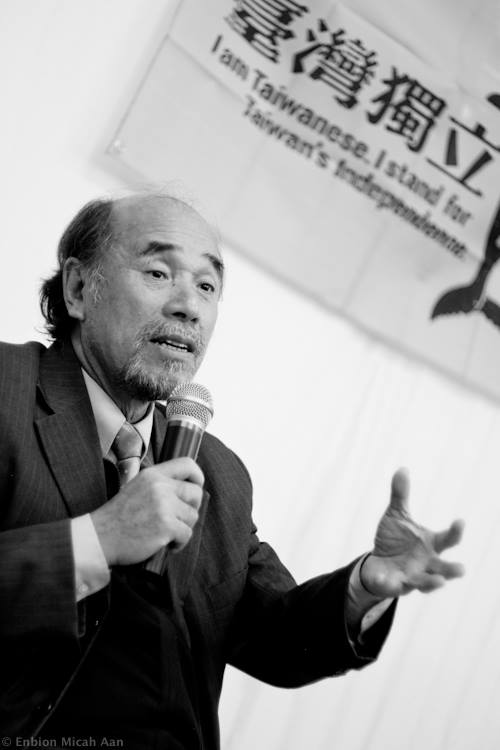

Tsay Ting-Kuei while speaking at a talk in New York City on December 21st, 2014. Photo credit: Enbion Micah Aan

Tsay Ting-Kuei while speaking at a talk in New York City on December 21st, 2014. Photo credit: Enbion Micah Aan

TTK: I think within reason, since nothing of that has harmed anybody’s life. Like I pulled down the Sun Yat-Sen statue in Tainan. With that action, we thought about it carefully, since the aim of non-violent protest is to accomplish demands in regards to issues. We don’t want to hurt anyone. We want to spread ideals of non-violence.

But when you have a softer demand that has no possibility of realization, that demand will eventually become higher and higher. It was like that AORFT as well. That is, you come to feel that the system has no way of fixing these problems. Because if they are fixed, the system would collapse. So why not? Overturn the KMT government-in-exile.

Taiwanese Independence and the DPP

BH: Can we talk about the DPP then? Because a lot of international observers say things like that after the appearance of the DPP or rather, the election of Chen Shui-Bian, that Taiwan’s democratization has been completed. The first thing I want to ask is like you said when the DPP was in power, like you said, some things were accomplished but not other things. But when Ma Ying-Jeou came back to power, all this just went back to KMT control. More or less, what I want to ask is how you would understand Taiwan’s democratization and Taiwanese independence in that light.

TTK: The DPP was formed to oppose to martial law out of the Dangwai Movement, although it was formed two years after the end of the Martial Law. Well, it was still on shaky grounds then, people were still afraid of being arrested. It’s one step at a time.

The Taiwanese people need to grasp the spirit of democracy, to decide for themselves, but the Constitution is designed to limit the power of the people. So to change, you need to continue to use methods of protest. The appearance of the DPP was a step forward for democracy, but in some aspects, the DPP also didn’t take care of everything very well. Again, the important point wasn’t grasped well. You could also say it’s strength wasn’t enough to accomplish its aims. But you asked why international observers were critical of referendum?

Photo credit: Enbion Micah Aan

Photo credit: Enbion Micah Aan

BH: For example, some international observers would think referendum is against democracy. That it doesn’t follow rule of law, because of populism and mass protest impacting government decisions?

TTK: The referendum is a means to set up good law. Ma Ying-Jeou says “rule of law” that quite often, in pushing for his laws under the mantle of rule by law. Well, this is what the Harvard-educated Ma Ying-Jeou tells us! But democracy is rule of law. Laws need to benefit the people.

BH: Related to what we were discussing before, I also have young peoples’ criticisms of the DPP in mind. Young people have doubts towards the DPP as a political party, for example, as was particularly visible during the Sunflower Movement.

TTK: After the DPP took power in 2000, the end result was a lot was accomplished, but Taiwan’s issues were too much, so there was no way to take care of all of the issues with the system in 8 years to begin with. That leaves a lot of people wanting. Perhaps the issues young people are attentive to were among those not paid attention to or taken care of very well by the DPP. During the student movement, we can see that young people are opposed to the KMT, but also doubtful about the DPP. Especially regarding Chinese policies. As such, during the student movement, students only allowed the DPP to occupy the area outside one of the entrances of the Legislative Yuan, and only allowed them in under approval.

After the movement, something that became visible in Taiwanese society was that people didn’t trust political parties, because people want to decide issues on their own. So now there are three forces in Taiwanese society. One is the KMT. The other is the DPP. The third is the so-called strength of the citizenry. There’s no particular organization, but before the widespread use of cell phones or the Internet, it was hard to accomplish anything in the lack of any organization. So after the movement, we can see that citizen groups, through the Internet, Facebook, and social media, can take action very quickly. This kind of strength will probably become stronger in the future, so it’ll have a large effect on social issues.

Photo credit: Enbion Micah Aan

Photo credit: Enbion Micah Aan

I think this is also a tendency of Taiwanese democratization. Eventually, these issues and hopes are placed in the hands of political parties. For example, Taiwanese independence with the DPP, and those identified with the KMT. It becomes a contest of two forces. Because of the transparency and exchanges allowed for by the Internet, slowly more people understand past history, the ideals we are currently striving for, and are taken in less by the trickery of political parties. From 2014’s local elections, we can see that the strength of the people has been established to a certain degree.

The Question of Democratic Solutions

BH: So you think that these problems of Taiwanese government and Taiwanese democracy should be resolved through referendum? Is the important part to depend on the people? And to depend on protest as a means of action?

TTK: I think because the government, the establishment, is a bureaucratic system, but usually there are minority groups that try to act upon government. When these groups try to enact their laws, it’s a process, so I don’t believe they will carry out changes on their own. With the strength of citizen or civil society groups, they want to change the system so need to put pressure on the government. Of course, there’s no way to wage guerrilla warfare in Taiwan, right? It’s using the strength of the people, non-violent protest, and lots of people, protest activities to add to the pressure put on government. Voting, too.

Audience member asking a question of Dr. Tsay during the December 21st talk. Photo credit: Enbion Micah Aan

Audience member asking a question of Dr. Tsay during the December 21st talk. Photo credit: Enbion Micah Aan

A lot of people believe Taiwan is already a democracy. I don’t believe so. Being able to vote doesn’t necessarily mean a democratic country. But a lot of people in Taiwan see voting as democracy and say things like, protest is unnecessary because Taiwan is already a democratic government. Taiwan can vote, but it’s not a democracy. It’s not transparent, for example, in regards to legislative processes in the Legislative Yuan, as well as the voting process for legislators. It’s not connected with the will of the people and direct democracy. How is that democracy? It is the same with the Executive Yuan and the Judicial Yuan. How do we fix this? The design of the government can’t be constituted as democracy.

Taiwan’s long-term social pressure situation has created some space for freedom. I can advocate Taiwanese independence and not be arrested in the present, for one. But fundamental change is harder. You have to continue to struggle and continue to attempt to make society understand why Taiwan needs to become a democratic, independent country.

A lot of people talk about it, a lot of politicians say that Taiwan is already is a democratic independent country. But the actual question is for Taiwan to become a democratic independent country in reality. This dream is foreclosed by the Constitution of the ROC, as can be seen in the international situation of Taiwan. Again, there’s no way to represent the voices of the Taiwanese people.

AORFT believes in raising awareness in the long-term, with our non-violent protest activities, we are also worried that people will become dissatisfied and turn to more extreme measures, which is why non-violent protest is so important for us. We don’t believe violence is right.

There are also people who say that because you oppose the system as a whole, you shouldn’t vote. We believe this isn’t the correct either. To be able to vote doesn’t mean that we agree or condone the system, it’s our power, because if we don’t participate, we won’t have power. If under pressure, why would you give up your power? It’s a very safe way of non-violent protest.

Accordingly, we tried to raise awareness during this past election. In the past, we advocated one candidate or another. But sometimes it’s that you support someone because their opponent is worse, not because they are better. So this time, for voting, we advocated eliminating the most rotten apples.

AOFRT and Taiwanese Civil Society

BH: Outside of Taiwan independence, does AORFT work with other groups on other issues? For example, I interviewed GCAA in regards to Nuclear Reactor #4, and they mentioned that Taiwanese independence activists came to participate in their activities.

TTK: Taiwan has the longstanding myth that politics is solely the domain of politics, economics solely the domain of economics, and environmentalism the domain of environmentalism, as though these things were not related.

For example, environmentalist groups or groups about other social issues, sometimes they will limit themselves and not allow political groups to attend their activities. Like I said before, if we are more political in looking at social issues, sometimes they won’t like for us to attend their activities. So we don’t push the issue, but we assist when they are low on strength. For example, in regards to environmentalism, with Nuclear Reactor #4, they don’t want to talk too visibly about the question of the political system as a whole.

Photo credit: Enbion Micah Aan

Photo credit: Enbion Micah Aan

But it’s a political problem. It was decided politically. Environmentalists want to pull in KMT and DPP legislators alike. That’s not possible with the KMT, but they try anyway and wish and hope, and so the issue has gone on for so long. If the KMT agreed to halt Reactor #4’s construction, it would have been halted long ago. With social issues, fundamentally, I think their view doesn’t understand that the key points are below the surface, so I think they’ve wasted a lot of time. It’s that once political problems are solved, that these other problems can find means of resolution.

Conclusion: “It can’t be asking other people to do it for you”

BH: My last question is, towards a non-Taiwanese reader, not just a Taiwanese reader, what would you say Taiwan needs to do?

TTK: From my experience, I came to America as an overseas student and learned Taiwanese history, then came to hope to change Taiwan. From when I was young to now, I think that Taiwanese democracy is making progress, even is the pace is slow, and sometimes doesn’t meet our expectation. A lot of things don’t look very hard, or that if everyone talked it over reasonably, we could accomplish it. Why doesn’t it change? Because behind it, United Front groups have their interests and they won’t let go freely.

For readers, I would say I hope people have faith in Taiwanese democracy. Not just to lose hope because we encounter difficulties or it’s slow going, and to turn towards more violent means as a result. If so, perhaps then Taiwanese democracy will suffer more difficulties. We need to use our wisdom to change people’s thinking.

Audience members at the talk on December 21st. Photo credit: Enbion Micah Aan

Audience members at the talk on December 21st. Photo credit: Enbion Micah Aan

Like I said before, a lot of times why people don’t understand is because people don’t understand Taiwan’s past, and how the ROC system came to be established. Once they were born, it was there, so a lot of people don’t understand the ROC isn’t a country. It’s a name, given by a government-in-exile. Taiwan is a country. The ROC is not a country. It’s just a government-in-exile. But a lot of people don’t realize this. Because there’s a “country” in “Republic of China”, they believe it’s a country.

A lot of people think our methods don’t have any effectiveness or use, but if we think about it, the establishment of democracy isn’t one day, or two days, one year, or two years. It’s over several hundred years. For America, it’s at least two hundred years or so, right? From 1987 after the end of martial law in Taiwan, democratization has seen progress. But 20 or so years later, there’s still a lot to be worked on.

Our hope is through the help of people from international society, the actions Taiwan’s people, we don’t need to wait two hundred years, we can understand how to resolve this problem, and through society’s understanding, things can be changed.

My hope is that in 2016 the KMT can suffer another defeat, including in the Legislative Yuan, and in regards to the presidential election. This would limit KMT’s power and make it easier to fix laws. It’s one step at a time. Every two years there are elections. So my hope is to realize a free Taiwan by 2020, with 2016, 2018, 2020, accumulating the strength of the people with each election.

Everyone needs to push for people’s power, it actually is quite easy, but for free democracy, you need to protect it and participate it yourself. Why did things fail when the DPP took power? Because the power of the people was too weak, people thought the DPP coming into power was enough and nobody monitored it. So it didn’t take care of things. People need to push down the power of the KMT and keeping an eye on the activities of the DPP.

It can’t be asking other people to do it for you. This is what a lot of people don’t understand, they think after voting, that’s it and there’s nothing to do.