by Brian Hioe

語言:

English /// 中文

Photo Credit: ABC

PREMIERING IN early February, Eddie Huang’s Fresh Off the Boat has been hailed as not only something for Asian-America, but for mainstream American television overall. Detailing a “Taiwanese-American” family after a move to Florida, the show follows the acculturation of an Asian family to the norms of America.

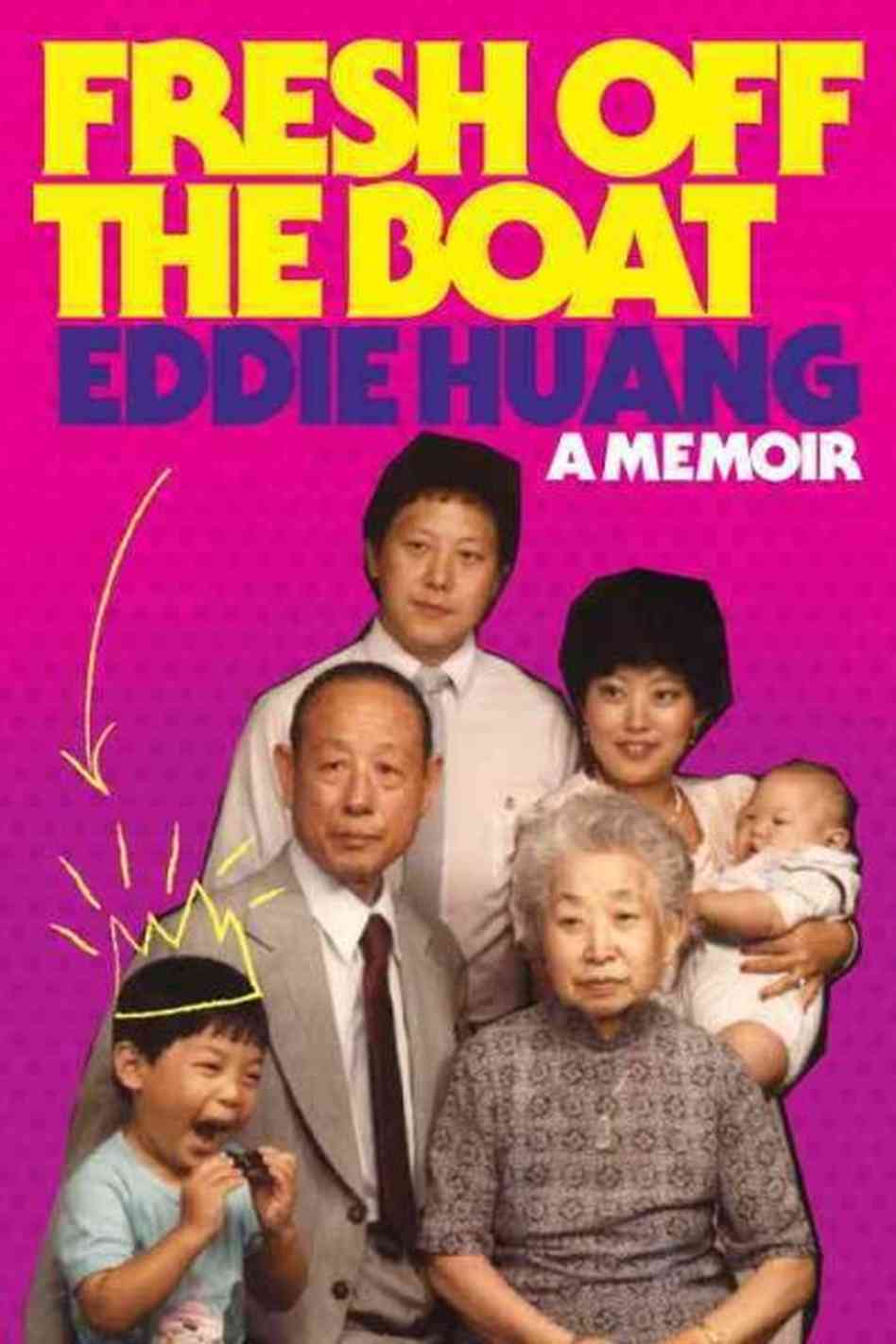

Fresh Off the Boat is based on and adapted from the bestselling memoirs of chef and media personality Eddie Huang. Huang is the host of the food program Huang’s World on Vice, owner of the restaurant Baohaus in New York City, and a vocal voice in the Asian-American community. Huang entered the restaurant business after a career first spent in law, then as a stand-up comic, but drew upon his experience from his father’s having owned a steak house when he was a child. Fresh Off the Boat, the television series, would be a liberal adaptation of Huang’s memoirs, which were published in 2013 and also titled Fresh Off the Boat.

Book cover of Fresh Off the Boat

Book cover of Fresh Off the Boat

Apart from being one of the first representations of Asian-Americans on mainstream American television, the show has been hailed as a historic victory for Asian-Americans who have struggled to find representation in the popular media. As such, that the show’s representation of the so-called “Asian-American experience” has resonated with many and been championed in part by the supportive voices of Asian-Americans is not surprising. It remains to be seen whether the show will be able to maintain its momentum, but to date, the show has won popular and critical approval.

Yet where Asian-Americans have tended to be rather unequivocal in the popular success of Fresh Off the Boat as a something of a victory in the representation of Asian-Americans in popular media, we might take a more critical stance. Part of my interest in writing this piece is a sense that no other person would write a critique coming from where I come from. I have the sense that Asian-American voices have been blindly affirmative of Fresh Off the Boat and that few others would come to a critical evaluation with similar concerns.

First off, I have a near identical background to Huang himself. Huang, who sometimes describes himself as a “Taiwanese-American” and other times as a “Chinese-American”, but also as a “Taiwanese-Chinese American” is the child of two waishengren, that is, descendants of those who fled to Taiwan from China after 1949 and subsequently constituted a 10% of the Taiwanese population that was politically dominant as a political and economic elite during the era of KMT rule.

Huang’s mother’s family fled to Taiwan after the Cultural Revolution, his mother, the youngest in the family, being the only one to be born in Taiwan. Huang’s mother’s family opened a highly successful textile factory, his grandfather eventually becoming a millionaire before immigrating to America to start over. On the other hand, his father came from a KMT family that came with Chiang Kai-Shek over to Taiwan, and Huang’s paternal grandfather being a high official in the Ministry of the Interior, who played a role in the land reforms of the 1950s. However, this grandfather of Huang’s seems to have left the KMT early, despite a promising career, out of opposition to the KMT government’s actions against native Taiwanese. Huang’s father, like his mother, was born in Taiwan as a result of this background.

I am half-Taiwanese to begin with, my father hailing from an Indonesian overseas Chinese family of Hakkan origin, which I suppose actually makes me half-Chinese despite my father’s identification as Indonesian rather than Taiwanese or Chinese and my general lack of family in mainland China. But like Huang, I share a waishengren grandfather who was a high ranking official in the KMT. This was my maternal grandfather, who was the general manager of the Bank of Taiwan. My maternal grandmother, however, was benshengren—the native Taiwanese of the 90% of the Taiwanese population who had been residents of Taiwan for centuries before the KMT arrived—hailing from Tainan, born and raised during the Japanese colonial period.

Where my mother’s family is concerned, despite being half-waishengren and half-benshengren to the point of such embodying such contradictions as speaking Mandarin with no less than a Beijing accent of all things despite being born and raised in Taiwan, yet also having completely fluent Taiwanese, my mother’s family has generally hewed towards waishengren identification and political support of the KMT. As a result, I think I may be able to understand something of Huang’s conflicting sense of identification, even if my claim is to be Taiwanese-American rather than Chinese-American while still participating in many of the concerns of Chinese-Americans.

Eddie Huang while eating at “Modern Toilet” in Ximending, Taipei. Photo credit: Huang’s World/Vice Media

Eddie Huang while eating at “Modern Toilet” in Ximending, Taipei. Photo credit: Huang’s World/Vice Media

Thus, part of my concern is about the representation of Taiwan in the television show. Certainly, one sometimes doubts if most Americans have heard of Taiwan or may just confuse Taiwan with Thailand, as no less than Barack Obama once made the mistake of doing. That Fresh Off the Boat is one of the first representations of Asian-Americans in American television to begin with, however Taiwan is represented in it will no doubt shape American perceptions of Taiwan for a long time to come. If Taiwan is represented as China, that seven million viewers tuned in for the first episode will certainly lead a great deal of Americans just to see Taiwan as such. And I suspect few other Asian-Americans, or even Taiwanese-Americans, would come to the show with this concern.

Yet on the other hand, where a show as Fresh Off the Boat is a valuable occasion to consider the internal tensions and contradictions of “Asia-America”, this would also be an opportunity to cross-examine Asia-America as a whole and its relation both to Asia and America. There is much regarding how Asian-Americans conceive of their understanding of themselves which might be discussed and the show provides a valuable opportunity to do so.

Will the Asian-American Revolution Be Televised?

IN EVALUATION of the cultural phenomenon of Fresh Off the Boat, one is immediately struck by the vast difference between Fresh Off the Boat the book and Fresh Off the Boat the television show. Certainly, the television show does not claim to be an adaptation of Huang’s memoirs, but rather to be “inspired” by Huang’s book.

Where Huang’s memoirs are largely a coming-of-age story, in which Huang’s family plays less and less of a role as Huang grows older and becomes increasingly independent, the television show takes place in the eternal childhood of the American family sitcom. More jarring altogether is the distance between the television show and Huang’s rather explicit, forthright, and sometimes confessionary narrative . Though the television show seeks to channel some of Huang’s irreverent tone, the overriding master narrative is that of the sanitized family sitcom.

Promotional image from Fresh Off the Boat. Center is Hudson Yang, who plays the young Eddie Huang. Photo credit: Bob D’Amico/ABC

Promotional image from Fresh Off the Boat. Center is Hudson Yang, who plays the young Eddie Huang. Photo credit: Bob D’Amico/ABC

Such are the perils of adaptation, perhaps. But what this points to in regards to the Fresh Off the Boat phenomenon is the need to read between the lines and parse out the means by which Fresh Off the Boat was able to be sold to mainstream, white America in spite of also having sought to push against the boundaries of possible representation in popular media. Huang’s memoirs thus need to be evaluated in separation from the television show. Huang cannot also be viewed directly as the auteur of the television show, over which he certainly seems to have less creative control.

Indeed, even if many Asian-Americans have hailed the show as a true representation of their experience, it strikes that a large part of Fresh Off the Boat generally just trades off of stereotypes in its characterizations. Though certainly well-acted, the Huang matriarch, Jessica Huang, taken up as the show’s breakout character, is a variant of the domineering Asian “tiger mom” stereotype who demands impossible levels of academic excellence of her children and micromanages her children and husband alike. Huang’s paternal grandmother, who lived with his family, stands out as having been made into less a character than prop, speaking only in Mandarin where the rest of the characters speak in English, but otherwise just wheeled around on a wheelchair as a passive object—this coming, rather demeaningly, out of the historical fact that Huang’s grandmother had bound feet and could not walk. The darker aspects of Huang’s father, Louis Huang, have also been glossed over with the character’s sanitization, where Huang’s actual father had a background in organized crime in Taiwan, violent tendencies, and seems a complex and fascinating figure. Huang’s youthful alienation has been largely emptied of any of the genuine emotion or pathos, this having been cut out to make a non-threatening product for the consumption of the American television audience.

To the extent that Fresh Off the Boat the television show has found success, it would seem to be by hewing the line of the master narrative of the American family sitcom. Indeed, there would seem to be something particular to the family sitcom as an American institution, by which the heterosexual, monogamous family is the marker of social stability. The television sitcom about such a family details the up-and-downs of this family, but always with a return to the status quo in which social order is safely reestablished at the end of the episode. While the family sitcom would orient around the white family in its inception, so it is, for example, that with the broadening of America’s racial horizons, we would see family sitcoms about black families as the Cosby Show, The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air, Everybody Hates Chris, and others. Now, we have our Asian-American family sitcom, apparently marking that America’s racial horizons have now become sufficiently broad to include Asian-Americans.

There certainly would be a simplification of the complexities which Huang’s narrative more fully embodies in the television show of Fresh Off the Boat. To my thinking, Asian-Americans should have immediately been suspicious in knowledge of the adaptation of Fresh Off the Boat as a family sitcom in consideration of Huang’s other work and the nature of Fresh Off the Boat as a coming-of-age narrative. But Asian-Americans were too eager to accept Fresh Off the Boat as a show which was representative of their experiences in such a fashion that one suspects the success of the show was vaguely overdetermined. So long as the show characterized some aspects of the Asian-American experience and did not make light of Asians in an overly offensive manner, one somewhat suspects the show would have found the adulation of Asian-Americans regardless. Very likely Huang’s public persona, founded upon defiance of the “model minority” stereotype, played a role in making the show seem sufficiently undermining of well-worn stereotypes to pass muster amongst Asian-Americans.

Though by no means marked by any shortage of well-acted parts, whether Hudson Yang’s depiction of Eddie Huang or Constance Wu’s Jessica Huang, the narrative of Fresh Off the Boat has to date been the cookie cutter one of the struggles of a family struggling to assimilate to America which, in the end, is affirmative of the American assimilation narrative rather than pointing to its limits. Where the show speaks to Asian-Americans, it is so far as it imbibes enough attributes of the Asian-American experience as to give the cookie cutter narrative of assimilation a quirky selling point compared to other narratives of assimilation.

Promotional image from Fresh Off the Boat. Photo credit: ABC

Promotional image from Fresh Off the Boat. Photo credit: ABC

Perhaps this in itself points to certain limitations of the “Asian-American identity” as it often conceives of itself. Was it really that for all the struggle of Asian-Americans to maintain the particularities of an experience distinguished from white America, or other “hyphenated American” groups, they were just yearning for acceptance from America in the end? We might ask ourselves why exactly it was that there was ideological need for Huang’s memoirs to be taken up in the form it was and why Huang’s memoirs could be taken up as such.

We must evaluate Fresh Off the Boat, Huang’s memoirs, in a separate register than how we evaluate Fresh Off the Boat, the television show. What we need to avoid is compressing the two as if they were simply two outgrowths of the same phenomenon. But we might thus begin with an examination of Fresh Off the Boat, the book, which provides the source material and perhaps also root logic for the television show so far as Huang constructed his public persona largely on the basis of his book.

In Search of Cultural Authenticity

HUANG’S MEMOIRS are generally quite readable. Occasionally, there are problems of narrative flow, but these are for the most part minor. There are also several episodes in which Huang goes off into a tangent, which probably could have been condensed for the sake of flow. Where there are problems, it is more often in regards to dialogue. As the art of memoir is an art of selective recollection, where one edits down the raw mass of one’s memories into something readable, dialogue must necessarily get the point across while sounding like natural speech. Sometimes Huang comes off as too didactic in the dialogue. His characters’ speech sometimes sound somewhat far removed from natural speech.

Yet overall, it is not surprising that Fresh Off the Boat would become a bestseller, so far as it is well-written and entertaining. Huang displays his talents most strongly in regards to his ability to characterize aspects of his personal experience and make it connect with those of his readers. Part of Huang’s ability to speak to Asian-Americans and resonate with their experiences in his memoirs would also lie in the breadth of his experience. Indeed, it is to Huang’s credit that apart from the usual struggles of fitting in at school or facing racial slurs from white kids, Huang hits on upon highly relevant experiences which are less often talked about. Episodes that come to mind, perhaps speaking to my own experience, include having to deal with insufferable white expatriates who try to prove that they have more knowledge about Asia than you, an Asian-American, in order to validate some sense of authenticity garnered from time spent in Asia. Or the experience of encountering differing permutations of second-generation Asian experience in, for example, in meeting Asian-Europeans as distinguished from Asian-Americans, never mind the different permutations of Asian-American experience itself.

However, what we can point to in the book is how Eddie Huang has constructed a representation of himself in the popular media that revolves around his apparent subversiveness of the Asian model minority stereotype through the inspiration he takes from black, hip hop culture. It would be such, for example, he would discuss in a 2012 profile in Observer about how he was called a “chigger”—a “Chinese nigger”—growing up because of his love of hip hop and rap and his status as a pariah because of his being Asian, although Huang cannot disguise his pride in the fact.

More broadly, Huang has sought to take on a vaguely radical persona in claiming inspiration from Malcolm X and the figures of black America who called attention to America’s racial and class injustice. In this, Huang has at other times railed against other Asian-Americans and even Asians as not subversive enough, too willing to embrace the “model minority” stereotype or Asian social norms based around collective authority, in which his iconoclastic persona is in part a reaction against. Regardless, Huang has also been emphatic upon a notion of authenticity, both in regards to his role as a chef of Taiwanese-Chinese cuisine who seeks to preserve the authenticity of his food, and in his self-consciousness of his Asian background. Huang seems to want to both preserve some notion of his roots while also reacting against them.

As he states in the book version of Fresh Off the Boat, in claiming that he does not fit in with ABC (American Born Chinese) types because he’ll “never be ‘Asian’ enough for [such] people” (158), given his subversive slant, the conversation which follows goes:

“Son, you playin’ yourself, you mad Asian! You know everything about the food, you speak fluently, you been back to Taiwan, you more Chinese than all these cats.”

“Yeah, but it’s different than what these ABCs expect. My dad isn’t an engineer or doctor, he got an automatic he used to to put on my head while I watched cartoons.”

“What’s that have to do with anything?”

“Everything! Dude, do you listen to the people in these meetings? They’re all dying to live under the bamboo ceiling and subscribe to the model minority myth; I’m not OK with that shit. They don’t understand that in China, Taiwan, or the Philippines, we can be whoever we want. In America, we’re allowed to play ONE role, the eunuch who can count. You seen Romeo Must Die! Jet Li gets NO PUSSY!” (158)

Indeed, this is quite telling where Huang’s masculinism is concerned. We will turn to a discussion of that in a bit. But where here Huang claims that “we can be whoever we want” in Asia, in other contexts he rails against Asians, too, on grounds rather eerily similar to what he criticizes Americans for doing to Asians.

As he states in an episode from after the opening of Baohaus:

One of the biggest challenges we faced came from cheap-ass Taiwanese people. I remember one chick came up to me and said, “You know, these baos are a lot more expensive than Taiwan. In Taipei, they are much bigger and cost less than a dollar!”

“Well, why don’t you buy a nine-hundred-dollar plane ticket and go buy yourself a one-dollar bao” (267).

You don’t like America? Go back to China, er, I mean, Taiwan, chink! Huang then tries in awkward fashion to connect this to his anger against culturally conformist Asians. He continues:

I had the ill flashback working at Baohaus. It was like Chinese school all over again, with these small-minded, conservative Asians that couldn’t understand shit if it wasn’t in an SAT prep packet (267).

One generally fails to see what the connection between cheapness about a bao and some form of Asian cultural slavishness is. What this gets at rather is Huang’s fundamental ambivalence about his Asian identity.

We might suggest a self-undermining element to Huang’s quest for authenticity. For example, where Asian-Americans and other minorities in America have at times railed against “cultural appropriation”, sometimes belying a hostility towards cultural hybridization and a form of cultural essentialism, one is at other times struck by Asian-Americans’ lack of concrete knowledge of Asia itself—this despite claiming the cultural heritage of Asia. Huang is certainly conscious of this contradiction. Huang speaks in his memoirs of how linguistic proficiency and knowledge of one’s cultural homeland sometimes becomes the object of competition between Asian-Americans seeking to hold up the validity of their cultural authenticity versus other Asian-Americans, evidencing a high degree of self-consciousness about the contradictory and conflicting ways in which Asian-Americans relate to their identity.

The rat race of the drive towards authenticity is something Huang is keenly aware of but, as evidenced above, Huang has the tendency to conflate several issues when he claims that Asian-Americans seem to have a lack of knowledge about Asia, while simultaneously denying he thinks he knows more—yet, in truth, he does seem rather proud of his high level of cultural knowledge and linguistic proficiency. Indeed, Huang claims to be beyond borders in one part of his book, but Huang often seems to be all about borders. He does not escape sometimes what he seeks to criticize. After all, sometimes the claim to transnationalism or a diasporic identity is just the magnification of the national identity, whereby one claims superiority to those of only one national identification through having a larger set of borders than those who are confined to smaller cultural borders rather than actually being “beyond borders”.

And where Huang sometimes suggests that America has wronged Asians in some way, he himself can be quite unreasonably hostile towards Asians—as an American.

Yellow Skins, Black Masks

WHERE WE MIGHT also criticize Huang’s self-adopted radical persona, it is in regards to the misogynistic attitudes he evinces in doing so as well as the radical chic nature of his claimed radicalism. As Frantz Fanon was perhaps the first to explicate in his Black Skins, White Masks, part of the colonial experience would be experiencing colonial subjugation as the wounding of the male nationalist ego, whereby the male colonial subject’s experiences colonial domination through the male colonial oppressor’s sexual domination of the colonial women. Thus, he desires the (white) women of the colonial oppressor in order to make up for his emasculation as such.

Huang in Kenting, Taiwan. Photo credit: Huang’s World/Vice Media

Huang in Kenting, Taiwan. Photo credit: Huang’s World/Vice Media

Fanon’s psychoanalytic mode of analysis is certainly relevant to the experience of second-generation Asians in America, but also the black American experience which Huang seeks to emulate. Arguably, the black male gangsta rap persona who flaunts his bling and is sexually promiscuous with a range of women, including white women, is a grotesque parody of and reaction against wealthy, white America whose social respectability masks the dark underbelly of class domination and sexual violence against women of color. Taking on the characteristics of white America in grotesquely distorted form becomes viewed as empowering—where men are concerned, anyway—but this also evidences Fanon’s insight that the colonial subject asserts agency by reenacting while also perverting the tropes of the colonizer’s power.

So, too, with Huang’s adoption of a hip hop influenced persona, and several discussions of how male Asian action stars “never get pussy” in his memoirs. Similarly, he relates several episodes of getting into fights or having the police called on him, arguably, in order to show off his masculine aggression. Huang’s attitudes in regards to women becomes a theme running through Huang’s work, as in his constant reference to “shawties” (which, by the way, Urban Dictionary defines as a “fine ass woman” for those unfamiliar with the term, as I was) in his Huang’s World segments for Vice. Or his constant commenting on the attractiveness of women who are caught on camera.

To return to Fanon, an illustrative episode in Huang’s memoirs is the chapter titled “Pink Nipples.” The chapter describes Huang’s curiosity about sex with a women with pink nipples (white women) as distinguished from brown nipples (Asian women) and eventually having sex with such a woman. One wonders to what extent Huang is aware of such attitudes on his part; his memoir includes a section with a brief gloss on feminism, but it stands strangely at odds with the rest of the book.

In regards to Huang’s adaptation of radical discourse, this would seem to be part of his general tendency towards performed radicalism. Everybody wants to be Malcolm X, sometimes it seems. It is of course a contradiction of the contemporary Cultural Studies and Asian-American Studies that the history of Asians working together with black radicalism in the 1960s and 1970s, have become uncritically affirmed as a model for how minority groups can work together to call attention to racial injustice in present day America. Where Huang discusses his classes in the Cultural Studies in his discussion of his college experience, he would seem to be a product of this phenomenon.

Perhaps a telling Freudian moment. Still from episode three of Fresh Off the Boat, “The Shunning.” Photo credit: ABC

Perhaps a telling Freudian moment. Still from episode three of Fresh Off the Boat, “The Shunning.” Photo credit: ABC

One suspects sometimes that even within the Cultural Studies, the exchanges between minority groups in America have sometimes been viewed as if the experience of minority groups can be treated within one unified, monolithic framework. The experience of American minorities as compressed within the Cultural Studies as though minorities all partake of one experience and have a natural alliance. Attention is not paid to the back-and-forth in exchanges between minority groups—and that such exchanges do not necessarily follow in a politically progressive direction.

The relationship between Asian and Black is one in which the cultural stereotypes of one group of the other can become mutually reinforcing and damaging to both groups. Indeed, it is, of course, not incredibly helpful to work against racial stereotypes in America if the result is that the emasculated Asian man, as in the cultural myth of the Asian micro-penis, then seeks to emulate black men in order to regain their sense of masculinity—seeing as black men are viewed as over sexualized by American society, as in the cultural myth of the gigantic black penis.

The Culture Mulcher

IT MAY BE such that we can understand why exactly Huang’s memoirs would be able to become mulch for the American culture industry in the form of the television show, Fresh Off the Boat. It may be that Huang’s attempt at iconoclasm was too easily able to be appropriated to the cultural mores of white America to begin with—it was, in fact, insufficiently radical where it criticized certain problematic cultural tropes but also embodied them. So Fresh Off the Boat was unable to resist appropriation by the American cultural machine. After all, part of the process of assimilation would be that it does not happen without struggle—but happens nonetheless. Where Huang may militate against the Asian assimilation narrative, it is not clear that militating against the assimilation narrative may not, in fact, be a part of the process of assimilation.

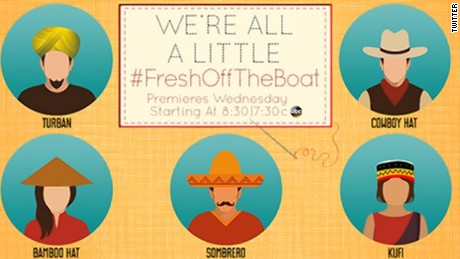

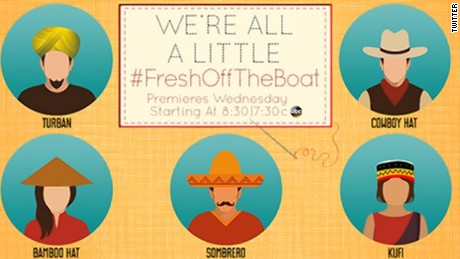

The following ad was posted on Fresh Off the Boat’s official Twitter account by ABC. Huang later would criticize the ad publicly for racial stereotyping. Photo credit: ABC

The following ad was posted on Fresh Off the Boat’s official Twitter account by ABC. Huang later would criticize the ad publicly for racial stereotyping. Photo credit: ABC

And those who would take up Fresh Off the Boat most enthusiastically may be Asian-Americans longing for assimilation, whether they admit to themselves or not. Huang’s self-proclaimed radicalism allows the show to appear subversive relative to other assimilation narratives, but this serves to allow Asian-Americans to get around the nagging thought that they might just be in some way giving into assimilation.

Huang, to his credit, is highly conscious of the limitations of representation. So it would be that he would publish in Vulture a criticism of his own show and its representation of his memoirs before Fresh Off the Boat premiered in order that he might raise the stakes of the game. Similarly, in his Huang’s World food program for Vice, Huang sometimes reacts against what is expected in order to push against the limits of his medium. In an episode set in Moscow, Huang brings on a guest, an American black man living in Moscow, who makes viral videos in Russia concerning being black, only later to attack him for trading off on racial stereotypes about blacks in Russia in order to attain popularity. In the same episode, Huang later attempts to include a working class immigrant Kyrgyz man as one of the guests in order that he can highlight more than just the Russian successful and wealthy.

But where we cannot view the television show of Fresh Off the Boat as a product Huang had much creative control, aspects of Huang’s original product do extend to the television show. The third episode of Fresh Off the Boat, for example, in part concerns the young Huang character’s lust for a white woman in an attempt to show off and become popular. One suspects vaguely that at times the television show struggles to throw off the constraints of the original book, which is what it would hope to do, but one can also suggest that the failure of the television show indicates the source material of the original work itself was perhaps too easily assimilated. This may have been socially overdetermined, too. And so, we might examine general questions of representation in Huang’s oeuvre.

In Search of Authenticity? Or In Search of America?

THAT HUANG had much more creative control over his Huang’s World food show than the Fresh Off the Boat television show makes his Huang’s World much more complex and sophisticated as a result, but we can also point to certain issues in his representation of Asia which undercut the conception of cultural authenticity he claims to aim for. Indeed, as mentioned, Huang can sometimes unexpectedly push the boundaries of popular representation, as particularly evident in his Moscow episode. However, at still other times, Huang can be found guilty of exoticizing foreign locales for the consumption of American viewers.

Huang in Chengdu, China. Photo credit: Huang’s World/Vice Media

Huang in Chengdu, China. Photo credit: Huang’s World/Vice Media

Though coming across as generally good-natured in his interaction with people he encounters, particularly in the way Huang seems to be drawn to playing with local children, Huang often comes off as quintessentially American as he goes to different international locations, only to stand out as at once an outsider through the bright colors of his clothing and his loud manner of speech.

Huang never makes the claim to have “insider knowledge” of a location that many other food show hosts would pretend to have, for example, in that he prominently showcases the local fixers which allow him access to culinary events in different locations.

In most cases, Huang attempts to be respectful of local custom, or to tease out the intricacies of local cuisine in regards to cultural practice rather than simply take what is different as inferior—although there are some examples when Huang simply finds himself unable to stomach some form of local food. Yet one also has the nagging suspicion that when Huang goes to different locations to search out local features, what he is looking for is the traces of America in foreign locations as a means of mediating the seeming appearance of irreconcilable cultural difference. So, then, his coverage of metal bands in Taiwan or Mongolia, or coverage of an American Chinese food restaurant in Shanghai.

Where Huang rises above hosts of similar programs is in his attempt to spotlight the social issues of different locations. It is such, for example, that while in China, Huang takes the occasion to pontificate upon the Great Firewall of China, feature an in-depth look at the lives of members of the Shanghai working class, and mining projects in Mongolia which threaten the lifestyles of herders.

But, once again, that Huang finds himself bound to criticize what he views as the collective mentality of Asian culture, on the other hand, he finds himself vaguely celebratory of that American cultural influence abroad has allowed for the opening up of individual expression, or rather, individual expression in an American vein. On the other hand, Huang also finds himself in the position of attempting to criticize the economic inequalities which have been brought about through American economic influence and finds himself caught in somewhat of a dilemma even when he does, in fact, demonstrate a knowledge of that he is dealing with a multi-faceted phenomenon.

Between Borders

THUS TO TURN towards an evaluation of Huang’s coverage of Taiwan and China while continuing to ask such questions, what in fact struck me was that his two episodes on Taiwan are significantly less respectful than his coverage of other locations, including China. This likely is because of Huang’s greater knowledge of Taiwan compared to other locations, as evidenced in the lack of fixers in his Taiwan episodes, and Huang probably feels more at ease to make fun of what he is familiar with. Indeed, while Huang does in fact represent himself as Chinese-American in his episodes in China, drawing upon his Hunanese ancestry by way of Chinese tradition which claims descent on the basis of ancestral origin, Huang is less mocking of China in the face of China’s evident political, cultural, and economic contradictions. By contrast, in Taiwan, Huang leans more towards identifying himself as Taiwanese-American or Taiwanese-Chinese-American.

But Huang is generally more irreverent of Taiwan, in regards to phenomenon as Taiwan’s betel nut girls, penis-shaped waffles at Shilin night market, or a cosplay show at National Taiwan Normal University, all of which predictably serves to bring out much chauvinistic commentary (thankfully, Huang did not venture to Tainan to cover strippers at temple festivals and funerals). Huang also at various times interacts with local Taiwanese, sometimes laughing at the older individuals who do not have any real ability to understand Huang.

Huang eating dinner with Freddy Lim and members of Chthonic. Photo credit: Huang’s World/Vice Media

Huang eating dinner with Freddy Lim and members of Chthonic. Photo credit: Huang’s World/Vice Media

In an attempt to spotlight Taiwan’s social issues, Huang interviews heavy metal musician and prominent Taiwanese independence activist Freddy Lim, frontman of Chthonic, and recent founder of the New Power Party. Huang’s treatment of Taiwanese independence is actually quite fair and balanced, with attempts made to point to differences in position among Taiwanese about the issue of Taiwanese independence in spotlighting the disagreements between members of Huang’s Taiwanese production crew and Lim, though this does not fully succeed because of Huang’s crew members’ poorer English relative to Lim. Where Huang seems to be critical of Lim himself, one also has to credit Huang’s acuteness in immediately jumping to the historical blind spot of Taiwanese independence politics in suggesting that if Taiwan were to shrug off the encroachment of China, it would just find itself under the hegemony of US—a fact many Taiwanese and Taiwanese-Americans have not thought through very clearly.

However, Huang is also mocking of Lim, in regards to Lim’s lack of knowledge of the heavy metal lyrics he sings, not knowing the meaning of the word “carrion” despite this being a English-language song lyric in one of his songs, laughing at the disjuncture between the cutesy furnishings of Lim’s apartment and Lim’s heavy metal persona, or spotlighting Lim’s periodic inarticulacy when unsure how to respond to Huang. When Huang spotlights social issues in China in a more serious manner, one has the general feeling that Huang is not incredibly aware of Taiwan’s continued problems of democracy, largely viewing Taiwan as having resolved most of its past social issues, and has not thought through Taiwan’s threat from China. Thus, while he attempts to depict Taiwan’s social issues out of his general consciousness of social issues, he does not seem to take them very seriously—it is less that he does not care, but that he views Taiwan’s problems as having mostly been resolved.

So, too, with many Taiwanese, to be sure. Yet at other points, Huang expresses political viewpoints which do seem drawn from his waishengren family background, for example, expressing while in China that while Communist rule and the Cultural Revolution served to destroy traditional Chinese culture, such culture was preserved in Taiwan and overseas Chinese communities in such a manner that it allowed this culture to return after the economic opening up of China but in which the preservation of traditional culture now faces threats from capitalist developmentalism. Certainly, this what the KMT would like to have people believe in order to preserve the belief of a unbreakable cultural tie between Taiwan and China. As stated previously, it is also a quintessentially American concern by which Huang is caught pointing towards the cultural liberalization that the establishment of the free market has brought about while also criticizing the economic inequalities brought about by the free market.

But this also evidences the simplicity with which Huang views non-American contexts by way of projecting his fundamentally American concerns onto Asian contexts; where Huang is all about preserving the authenticity of traditional culture in America, rather than giving way to the American cultural appropriation of tradition, he emphasizes the need to preserve tradition in Asia against the influences of the free market which are threatening to cultural tradition after the aberration of past Communism. What the task facing Chinese is for Chinese to try and preserve past tradition. This is, of course, hardly so simple when against the capitalist present, it is precisely the history of China’s Maoist past that Chinese often turn to in order to resist the destabilizing influences of the free market—another form of holding “traditionalism” up against the capitalist present, but a very different traditionalism than the one that Huang would value. History is, of course, not so easy a mess to work through when one comes in from afar.

Chinese? Taiwanese? American?

ALONG SUCH lines, in regards to Taiwan, one is struck by the sense that Huang’s identification as a “Taiwanese-Chinese-American” is conditioned by American perceptions that do not distinguish between Taiwan and China and bring Huang to a sense of identification with China. Huang’s grandparents are, of course, from mainland China, and Huang originates from a waishengren family, but his parents were born in Taiwan. Huang appears to speak Mandarin with a slight Taiwanese accent as a result and, though this might just be my imagination based on similar experience, it strikes me that he is slightly slower in his responses to mainland Chinese whose speech patterns differ substantially from Taiwanese Mandarin. As evidenced in his memoir and his two episodes featuring Taiwan, most of his childhood memories involving going back and visiting relatives seem to have to do with Taiwan, rather than China.

Huang’s mixed sense of identification is not a real issue, seeing as he was born in and grew up in America and can decide to identify as whatever he would like, where a claim to be “Chinese” would be more problematic had he grown up in Taiwan. Waishengren families that identify with mainland China do in fact have the tendency to refer to themselves as “Chinese” rather than “Taiwanese”, but also to use the terms interchangeably.

Promotional image for Fresh Off the Boat. Photo credit: ABC

Promotional image for Fresh Off the Boat. Photo credit: ABC

If Huang accepts the idea of a “cultural China,” existing in some realm in which it can be passed down through generations of ethnic Chinese abroad despite subsequent lack of contact with China this may be a result of his waishengren background and family upbringing. Nevertheless, one might suggest that there is a means by which this has been conditioned by America society. Americans, after all, as citizens of the “melting pot”, define national descent on the basis of long-term descent, by which one can be “Italian”, for example, despite having been in America some odd generations without any contact with Italy, but continue to claim Italian culture and history as a wealth of resources to draw on for a sense of cultural identity.

But to the extent that all of this past history is at a remove for Huang, one is also struck by how Huang’s ancestral history has become the object of pride for Huang in haphazard fashion. Huang seems rather proud of his maternal grandmother’s Hunanese descent where the most famous Hunanese of Chinese history seem to be Mao Zedong and General Tso of General Tso’s Chicken fame, even where, for example, he is otherwise critical of Mao’s disastrous social policies and of American Chinese food’s strange history of perverting American knowledge of authentic Chinese food. At other places, he seems rather proud that his grandfather was a high level KMT government official and his mother came from a background of wealth in Taiwan, although one suspects he does not particularly know this history very well. Yet where Taiwanese history and culture is not known in America, it is Chinese history which provides more to draw on for a sense of cultural identity.

At a later date, it will suffice to point out how the television show, Fresh Off the Boat, has largely not made very many distinctions between Taiwan and China to date. But Taiwanese-Americans have generally been affirmative of Fresh Off the Boat in all its forms because it has allowed for them to have a sense of representation, period. Thus, I think there is the need to point out the contradictions present in Huang’s sense of identification where it can offer a useful object lesson.

While I think Chinese reacting to Fresh Off the Boat will see Fresh Off the Boat as the weird, puzzling inverse to the cultural phenomenon of Chinese television shows about Chinese immigrants moving to America as Beijingers in New York, it strikes me that there is less of a need for China to defend its cultural representations abroad given that all the world knows China. Where I am concerned, it is more important to take into account the Fresh Off the Boat phenomenon’s representation of Taiwan, given the world’s lack of knowledge of Taiwan. On the contrary, those Taiwanese who are aware of the show have usually been affirmative of it on similar grounds as Taiwanese-Americans or Asian-Americans.

While Huang is perhaps right to militate against conformist social norms, Huang is held up as the hero who is able to represent Taiwan in America. As Taiwanese sometimes hold up the specter of conformist Asian society, as counterposed to the utopia of individuality that is America, Huang has even been praised on those very grounds of his perceived American individualism. Taiwanese have not yet made demands of Huang, so far as, for better or worse, he will come to represent them. And they should.

Why Criticize?

CAST AND STAFF of Fresh Off the Boat, particularly Constance Wu in a rather cogent interview with Time Magazine, have sought to allay criticisms by citing the impossibility of representing all Asian-American experiences in merely one television show. Likewise, staff members have cited the historic nature of Fresh Off the Boat, and that despite its many problems, the show is historic and so must be taken in its significance as such.

No doubt, there is a lot of truth in regards to the first point. You can’t represent everyone in one product. So it is why I have not, for the most part, conducted a critique of Huang and Fresh Off the Boat focused primarily on the grounds of his failure to represent the Asian-American experience as I would have, to pit my version of the Taiwanese-Chinese-American experience against his—even as I have called attention to the need for Huang and Fresh Off the Boat to be attentive to the representation of Taiwan so far as it will be significant for Taiwan.

Huang and Philochko. Photo credit: Huang’s World/Vice Media

Huang and Philochko. Photo credit: Huang’s World/Vice Media

But there is something remarkably suspect about the claim that criticism is unwarranted because of the historic nature of Fresh Off the Boat. Just as the claim to a historic first can be incredibly empowering, so too, has “history” served as a rationale by which minorities were denied their rights through the claim that they should wait their turn for the eventual redemption by history—this being a means of silencing criticism.

When somebody has entered the public spotlight in such a manner as Huang has, should he really be exempt from criticism? Huang cites his admiration for Barack Obama in Fresh Off the Boat, the book, so far as Obama was pioneering for minorities in America as the first black president. As such, “Obama was, is, and will forever be my homeboy” (224). But seeing as he is, after all, now the president of the United States, should we not criticize him, as well? When you enter the limelight, you’re never off limits, as far as I’m concerned. I say that in regards to myself, too, frankly.

And Huang is all too aware of the problems of when any single individual becomes representative of a community as a whole. As he states in his Moscow episode of Huang’s World, in criticizing black Brooklynite Philochko, who creates viral videos playing off of stereotypes about black people in Russia in order to attain a status of media celebrity, on the grounds of “haphazardly exporting stereotypes…and stigmas into a foreign country that doesn’t have the context to process what it’s facing”, Huang states:

We have a global problem. And my show’s included. All of us want to know more about each other and we have a desire to understand where we’re from. But in that quest, we gotta resist the temptation to allow any individual or singular voice to speak for an entire community.

In that, he is absolutely right.