by Symin Chan

語言:

English /// 中文

Photo Credit: 白象文化/聯合報

Translator: Brian Hioe

AT THE START of 2017, the newly released computer “Detention” (返校), which quickly became an international hit, used the Taiwanese language songs “Goa̍t-iā-chhiû” (“Worries In The Moonlit Night” or 月夜愁) and “Bāng Chhun-hong” (“Facing the Spring Wind” or 望春風) and other songs as background music. In 2017, the winner of the Golden Melody Award for best male Taiwanese song was Hsieh Ming-Yu (謝銘祐). His record “Last Year” (舊年) used a number of Taiwanese songs which were popular during the Japanese colonial period. What treasures do Taiwanese songs contain that they can resurface like this?

In the 1930s, Taiwan had a lively, energetic, and plentiful record industry. In a short twenty to thirty years, over a thousand records of all sorts of varieties of music were published; the streets and winding alleyways of Dadaocheng were full of koa-á (歌仔), pak-koán (北管) and lâm-koán (南管), with traditional Chinese opera, popular songs, or new koa-á, etc., and the accompaniment of “benshi” (辯士) film narrators for silent films. [1] Not only that, but the first generation of Taiwanese students who studied western classical music in Japan had returned and entered the record industry, writing popular songs or going out to collect folk songs. Innovations such as lâm-koán musician Pan Rongzhi (潘榮枝) adding jazz to lâm-koán took place. “Bāng Chhun-hong” and other works were born in this kind of splendid period. Before receiving the attention of music scholarship, these songs were only considered “Taiwanese folk songs”, without knowing who wrote the song or lyrics, and the names of Teng Yu-hsien (鄧雨賢) and Lee Lim-chhiu (李臨秋) had nearly been forgotten.

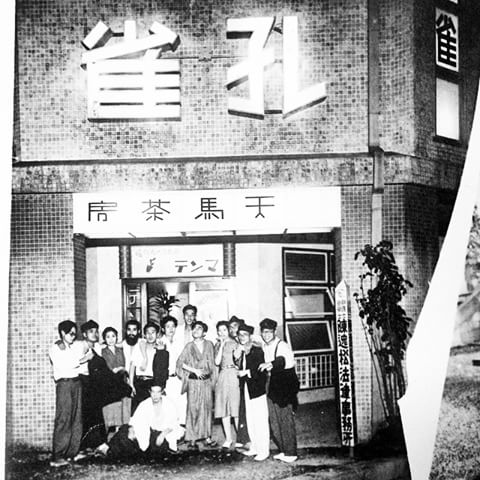

The medical students of Taipei Imperial University (now NTU) took this picture in front of Tianma Teahouse in 1941. Photo credit: Li Kuncheng

The medical students of Taipei Imperial University (now NTU) took this picture in front of Tianma Teahouse in 1941. Photo credit: Li Kuncheng

This historical situation was because of the oppression of the KMT government, which using its political power wanted for the cultural life of the Japanese colonial period to be forgotten, with such songs classified as forbidden songs, as well as preservation or research into relevant music materials. It was only until the 1990s that the pieces could be put together from the record collections of lovers of records from the 1960s, 1970s, and 1970s. [2] The lack of information on Zhan Tianma (詹天馬) is a case in point. The 1947 228 Massacre began in front of the Tianma Teahouse (天馬茶房). Zhan Tianma spent his life as the boss of a tea shop, and at the same time was the composer of Taiwan’s first popular song “The Peach Girl” (桃花泣血記). [3] Zhan Tianma’s influence can be seen in contemporary plays and film, but we unexpectedly have no way to confirm his date of birth and death. [4] The lack of historical materials partially was a result of the chaos of the war, but actually long-time oppression and threats are the key reasons as to why they became fragmented.

The Taiwanese record industry was at the same level as with Korea, Japan, and China in terms of production, but the historical materials they have produced are much more complete and well preserved compared to Taiwan, and have extensively developed musical research. At the time, Korea and Taiwan were both colonized by Japan, and were influenced by Japanese music while also differing from it. How Japanese policies affected the record industry was also different, these differences and the cultural independence of Taiwan and Korea had a close relation to the development of cultural self-identification. In May 1940, the Wang Jingwei government sent a southern Chinese musical research delegation from China to Taiwan and then to Japan. In the classification of the Japanese colonial period, music from Guangdong and Taiwanese records were classified under the same category. From this incident, one can observe the ambiguous position Taiwan has caught between China and Japan. With the rise of independent Taiwanese identity in the present, with endless discussion about the stages of national identification, the cultural activities of that period are especially worth using as a reference.

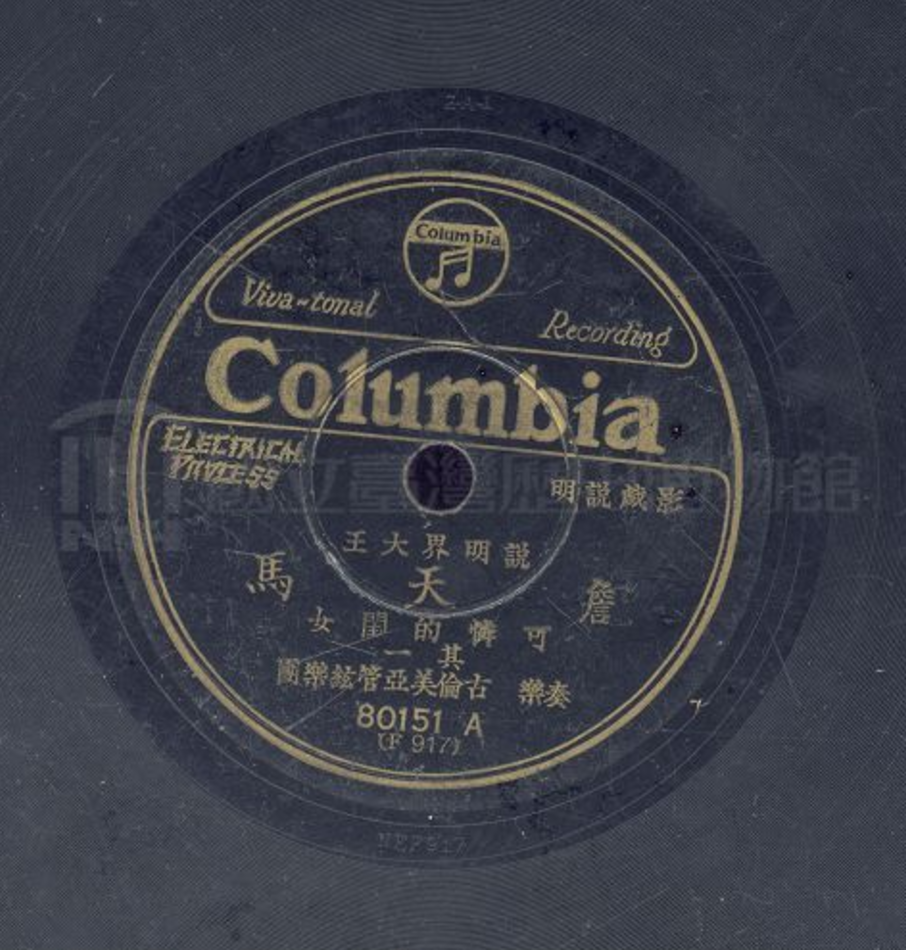

The narration of Zhan Tianma for the film “The Poor Girl” was published by Columbia Records in 1931, and he was given the name “The King of Film Narrators”. Photo credit: National Museum Of Taiwan University

The narration of Zhan Tianma for the film “The Poor Girl” was published by Columbia Records in 1931, and he was given the name “The King of Film Narrators”. Photo credit: National Museum Of Taiwan University

The Taiwanese record industry during the Japanese colonial period did not only fluctuate according to commerce and trade, but according to cultural identification, and the effects of musical classification. Under the conditions of oppression from the KMT, we can see even more clearly the strong influence of politics. But in this age of rapid digitalization, in which everyone can produce music, have we thought about why we need music? What kind of music do we need? Does music produced today have a relation to contemporary society? If we want to investigate the core issues of cultural creation, the political level is one aspect which must be highly considered.

[1] Koa-á can be said to be the precursor of koa-á-hì, this koa-á-hì and the koa-á-hì we are familiar with today are very different, with distinct differentiation in musical study.

[2] Thanks to collectors Lin Taiwei, Dr. Xu Dengfang, Li Kuncheng, Lin Liangzhe, Huang Yuyuan, and many other collectors and researchers who are not raised but worthy of respect, for their contributions to the collection and preservation of musical materials. At the same time, because these collectors have contributed much, up to the present at the NTU Musical Materials Database, the NTNU Digital Archives Program, and the National Museum of Taiwan History, you can hear 78 records.

[3] Taiwan’s first “popular song” here refers to a song that, every person in an area has passed on a song, or the record has created a sensation. What should be classified as a “popular song” is something discussed within the field of musical study. As for whether “Taohua qi xieji” is Taiwan’s first “popular song”, there are multiple views.

[4] Zhan Tianma’s original name was Zhan Fengshi (詹逢時), his second wife Zhan Jinzhi (詹金枝) later became highly religious after his death, something described in more detail on the Taichung Bodhi Renai House website. At present, we can only infer from information about this that Zhan Tianma was born in 1901 and died at 52 from heart disease.