by Brian Hioe

語言:

English

Photo Credit: Ten Years

The Controversy Over Ten Years

HONG KONG film Ten Years would have come to the world’s attention after unexpectedly winning best film at the Hong Kong Film Awards. A dystopian speculative fiction film about Hong Kong in the near future under Chinese rule, the win has provoked controversy.

The win of the film is remarkable, considering Ten Years’ status as a independent film produced on a shoestring budget of $600,000 HKD ($77,000 USD) and used actors who were mostly volunteers. The film was originally only released in one theater, only being shown at eight theaters at its peak, and having a release time of eight weeks. This did not prevent the film from garnering six million HKD at the box office, beating out even the latest Star Wars film.

The film was later pulled from theaters, despite high demand, a move many have seen as self-censorship by theaters for fear of authorities. However, private screenings at universities and alternative venues have kept the momentum going. On April 1st, the film was screened at 34 different locations, including projection onto the LegCo complex which houses Hong Kong’s legislature.

Nonetheless, the victory of Ten Years has seen no small amount of controversy because of the unorthodox nature of its victory. Critics have pointed to the low production values of the film or that the film did not take any awards for best director or best cinematography to suggest that this is an instance in which politics has taken art hostage.

Ten Years, of course, depicts the highly politicized matter of Hong Kong’s relationship with China, issues of which have been increasingly foregrounded since the 1997 handover of Hong Kong from British control to Chinese control. The film also comes in the wake of the 2014 Umbrella Movement, although the film was in planning before the movement.

Industry magnates such as Peter Lam, who has been a vocal critic of the win, have threatened to boycott the Hong Kong Film Awards in the future. Voting for the Hong Kong Film Awards, however, takes place through a combination of voting by members of a professional jury, industry professionals, and public voters in two stages. On the flip side, vocal critics of the win have been accused of harboring pro-Beijing sentiment which, particularly in the case of film industry magnates, may be true in some cases. It would certainly be in their market interest to do so.

Unsurprisingly, Ten Years’ win has led to the Hong Kong Film Awards as a whole not being reported on within China. Chinese state-run media has criticized the film as “totally absurd” in its depiction of a dystopian future and “a virus of the mind.” This has not prevented curious Chinese netizens from seeking out the film online, though to the bemusement of many netizens, this has in some cases led to downloads of the wrong film.

We might take a look at the film then, to provide a critical evaluation.

Five Segments

COMPRISED OF five segments produced by five directors, Ten Years offers visions of a future Hong Kong in the years 2020 and 2025. If critical attention has honed in on the “dystopian” elements of the two segments which take place in the year 2025, the film depicts a Hong Kong in the process of transition under Chinese rule. The first three segments of the film take place in 2020 and the last two in 2025.

The five segments take place in roughly chronological order in this future timeline. However, even in the segments which are set in 2025, the focus is still on a Hong Kong losing its democratic freedoms and cultural identity because of Chinese rule. In this way, even if the stark vision of a future Hong Kong is what has garnered attention for the film both in Hong Kong and in international media, the overall trajectory of the film is oriented around this sense of loss.

The first segment, “Extras”, depicts the collusion of the Chinese Communist Party, pro-Beijing politicians, and triad members to conduct a staged assassination attempt. This is in order to raise a panic in order to pass the restrictive National Security Law, which would diminish Hong Kong autonomy in the name of public security. The National Security Law is a real-life proposed law, which was the Hong Kong government attempted to pass into law in 2002, but shelved after demonstrations.

Still from “Extras”. Photo credit: Ten Years

Still from “Extras”. Photo credit: Ten Years

Lawmakers behind the push for the National Security Law, such as then-Secretary for Security Regina Ip, were among the antagonists of the Umbrella Movement. The collusion of triad members with pro-Beijing politicians and members of the CCP was based on the real-life collusion of gangsters and pro-Beijing forces which was visible during the Umbrella Movement and remain visible in Hong Kong in its aftermath.

Though the weakest segment of Ten Years and not exactly a strong opening for the film, hampered as it is by the cartoonish acting by characters playing pro-Beijing lawmakers and CCP officials and generally lifeless acting by those playing other characters, “Extras” is notable for its attention to the socially marginalized. The protagonists of the segment are the two low-ranking triad members pushed to conduct the staged assassination attempt, who are driven by their poverty to their actions, but in the end simply the puppets of the CCP; at the conclusion of the segment, the two triad members wind up dead, having been misled to think that they would be allowed to escape after the fake assassination.

Still from “Extras”. Photo credit: Ten Years

Still from “Extras”. Photo credit: Ten Years

In particular, the two would-be-assassins are depicted as a poor, Cantonese-speaking mainland Chinese immigrant who is unable to speak Mandarin, and a young Indian man who is an immigrant to Hong Kong. The two characters are depicted as marginalized on the basis of their backgrounds, which is why they are driven to this act of desperation, and in that way they are represented as wholly sympathetic characters.

The second segment, “Season of the End”, would be the odd segment out of the film. Vaguely resembling something like Hiroshi Teshigahara’s adaptation of Kobo Abe’s novels, “Season of the End” is a surrealistic take on a man and women who preserve the destroyed remnants of demolished houses as taxidermy. Questioning whether or not they are truly alive, whether their obsessive acts of preservation is nostalgia for a past which can never return, and haunted by the specter of their pasts, in the end the man decides that he himself should die and be made into taxidermy. The final shots of the film suggest that the woman plans to follow suit. No other characters appear in the segment apart from the man and the woman.

Still from “Season of the End”. Photo credit: Ten Years

Still from “Season of the End”. Photo credit: Ten Years

Probably the most well-composed out of all the segments, “Season of the End” would be closer to art film fare, with its highly aestheticized plot and mise-en-scène. Though jarring in contrast to the rest of the film—one suspects that most viewers were just perplexed by how it fit into the rest of the film—“Season of the End” recasts the aims of the film in philosophical terms despite standing at odds to the more conventional style of the other segments.

The third segment “Dialect,” depicts the plight of a Hong Kong taxi driver after legislation is introduced limiting the areas taxi drivers who can only speak Cantonese can operate in. The focus of “Dialect” is on the sense of alienation felt by its protagonist as a product of increasing restrictions placed on Cantonese. Unable to learn Mandarin, the driver is shown as alienated from his son, who grows up speaking Mandarin at school, and increasingly uses Mandarin vocabulary despite speaking Cantonese at home.

Still from “Dialect”. Photo credit: Ten Years

Still from “Dialect”. Photo credit: Ten Years

The driver is increasingly unable to find work because of his inability to speak Mandarin and the growing predominance of fares who only speak Mandarin or are only willing to speak Mandarin. He also experiences alienation from the aspects of the changed social environment after the restrictions placed on Cantonese when he becomes unable to communicate with other individuals because of his only being able to speak Cantonese; in an especially well-staged scene, the driver becomes alienated from even technology itself, when his GPS is unable to recognize Cantonese or the driver’s poorly pronounced Mandarin.

Indeed, the emphasis on “Dialect” would seem to be on the colonization of language. As the driver comments at one point, “Before, you can’t find a job if you don’t speak English. Now you need putonghua for everything.” Such would be linguistic alienation under first British, then Chinese colonization, the implication seems to be. Along such lines, at one point in the film, the driver finds himself confronted by a Caucasian passenger who he first tries to speak to in English, but who unexpectedly responds to him in Mandarin. Likewise, the film depicts conflict between the driver and other Hong Kong taxi drivers who have become able to speak Mandarin and confront him for picking up passengers in violation of the rules for non-Mandarin speaking taxi drivers. This would be the confrontation between someone who has accommodated themselves to the new colonial regime and someone who has not internalized the new colonial mentality.

Still from “Dialect”. Photo credit: Ten Years

Still from “Dialect”. Photo credit: Ten Years

The fourth segment, “Self-Immolator” would be the segment which most directly harkens to the Umbrella Movement. The first of the segments of the film to take place in 2025, “Self-Immolator” is shot as though it were a documentary and revolves around student Hong Kong independence activists after one of their own dies during a hunger strike after arrest and a self-immolation by an unknown individual takes place in front of the British consulate-general.

Interspersed with fake or semi-fictional interviews with members of society and experts, “Self-Immolator” primarily depicts the internal tensions among young Hong Kong independence activists regarding tactics. This is concerning the question of whether to stick to non-violent tactics or whether the use of violence should also be on the table, what responses to increasingly repressive authorities should be, whether a death or suicide can be invigorating of the movement. As these are questions faced by every political movement at some point, it is quite astute of “Self-Immolator” to hone in on such issues. “Self-Immolator” also addresses the question of whether there is anything to be gained for Hong Kong by appealing to the British.

Still from “Self-Immolator”. Photo credit: Ten Years

Still from “Self-Immolator”. Photo credit: Ten Years

Continuing the thread started “Extras,” “Self-Immolator” is notable in depicting multiracial character, with the depiction of an interracial relationship between two of the student activists, one of which is South Asian. This is foregrounded when this South Asian character is at one point confronted for speaking Cantonese despite being South Asian and called out for not being “Chinese” (中國人), to which she responds that because she was born in Hong Kong, she is a “Hong Konger” (香港人).

“Self-Immolator” would also suggest that a future Hong Kong may become something like Tibet in regards to self-immolations, raising the question of China’s “ethnic minorities”. Though not without elements suggesting Hong Kong’s civilizational advancement relative to China, the concluding twist in “Self-Immolator” is that the eponymous self-immolator whose identity has remained unknown throughout the segment turns out not to be one of the students to be an eighty-year-old woman that is a frequent participant in student demonstrations—who, presumably as an immigrant from China, is a survivor of the Cultural Revolution and the Tiananmen Square Massacre. The final shot of “Self-Immolator” is of a burning umbrella carried by this woman, an obvious reference to the Umbrella Movement.

Still from “Self-Immolator.” Photo credit: Ten Years

Still from “Self-Immolator.” Photo credit: Ten Years

The last segment, “Local Egg”, begins with the closing of the last chicken farm in Hong Kong as a product of Chinese efforts to stamp out anything “local” in Hong Kong. Also set in 2025, by this time, Cultural Revolution-style youth guards are sent out to report on anything going against official regulations in Hong Kong. This includes any mention of the word “local,” as well as banned books such as foreign media. Youth guards are shown throwing eggs at bookstores selling prohibited material and marching through Hong Kong in Red Guard-style uniforms.

Still from “Local Egg”. Photo credit: Ten Years

Still from “Local Egg”. Photo credit: Ten Years

The motivating conflict of the story is that between a grocery store owner who seeks to continue selling local eggs, implied to be because of fear of contaminated food from China, and his son, who is made to participate in the youth guard. The protagonist, the grocery store owner, attempts to instill in his son the critical thinking skills not to just follow orders from his superiors unthinkingly. In the end, the conflict is resolved through the discovery that the son secretly tips off booksellers who are about to be targeted by the youth guard and has in fact been thinking critically, and that Hong Kong booksellers have been hiding banned materials in a secret space, preserving a space of freedom from censorship.

Still from “Local Egg.” Photo credit: Ten Years

Still from “Local Egg.” Photo credit: Ten Years

The implication seems to be that even in an era of repressive censorship, a space can be carved out to prevent things from being lost, as a way of pragmatically surviving without giving up one’s values. Interestingly enough, this seems to be at odds in some sense with the message of “Self-Immolator”, which does not actually rule out the justifiability of violence or suicide and in some sense actually embraces an ethos of self-sacrifice, with the self-immolation of the old woman depicted as a noble act.

Ten Years and Question of Arts and Politics In the Hong Kong Film Industry

IT IS INTERESTING to note that critics of Ten Years’ win at the Hong Kong Film Awards have attempted to hold art above politics in claiming that Ten Years’ win is art being held hostage to politics. But when is art ever not political? All the more so when it comes to film awards, which tend to be highly politicized affairs. The claim of art for art’s sake is all too often just an attempts to police the borders of what constitutes “art” or “high culture” because of politics, while at the same time claiming that this is an unpolitical act.

The opposite of Ten Years’ win would seem, for example, would be the snub of Taiwanese film Thanatos, Drunk in favor of a win by Hou Hsiao-Hsien’s The Assassin at the Golden Horse award, despite Thanatos, Drunk easily comparing to the masterpieces of the Taiwanese New Wave and being hailed by many critics as the best Taiwanese film in decades—the reason being that Thanatos, Drunk was too Taiwanese, seeing as the film was filmed almost entirely in Taiwanese and made the conscious effort to represent Taiwan and its specificities. By contrast, the Chinese-centric nature of The Assassin was what led to its victory. So it was, then, that Thanatos, Drunk received nearly no international attention, having won very little on the film festival circuit in Taiwan.

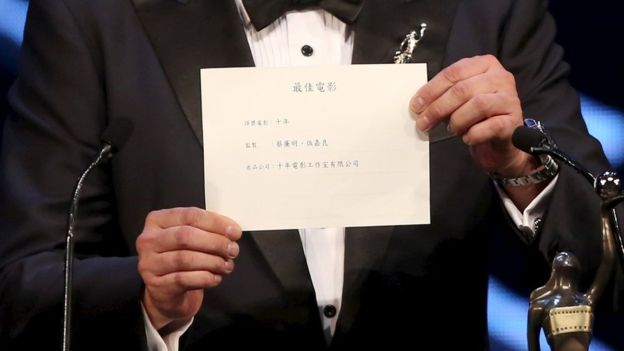

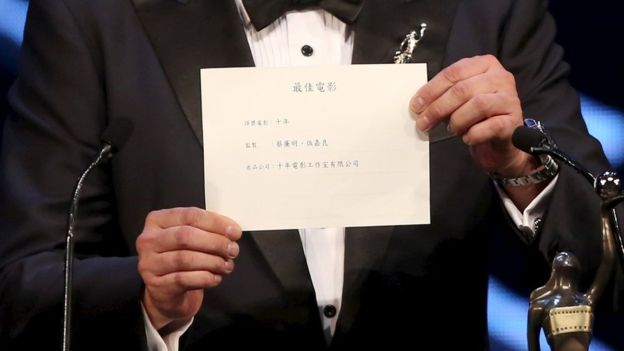

Title card with Ten Years’ win on it. Photo credit: Reuters

Title card with Ten Years’ win on it. Photo credit: Reuters

But if Ten Years’ win in Hong Kong has spotlighted the film internationally, does the film deserve the win on the basis of its artistic credibility? Certainly, the film is far more than just fear mongering propaganda, as Chinese state-run media accused it of being. In elements such as its sympathy towards South Asian immigrants to Hong Kong and even Chinese immigrants, the film has taken a stand, making it clear that its definition of Hong Kong rests on civic identification rather than ethnicity. In this regard, the film is daring and takes a stance regarding dividing issues in Hong Kong.

If, as critics have called attention to, the film’s low production values and its unevenness in quality, perhaps all the more so that Ten Years is a remarkable film. Great works of art are sometimes those which linger in historical memory because of how they resonate with the zeitgeist of a certain moment in time. This would be true of Ten Years, which has resonated very much with the post-Umbrella Movement Hong Kong.

Film poster for Ten Years. Photo credit: Ten Years

Film poster for Ten Years. Photo credit: Ten Years

Film would be a medium that tends to be controlled in the hands of very few individuals. As a result of the equipment costs, the numbers of staff needed, and the difficulties of distribution, large film companies are needed to produce the kind of film which can win awards on the film festival circuit. We see this in Hong Kong particularly with the influx of large Chinese film production companies that local filmmaking cannot hope to compete with. Ten Years goes against the global trend of films produced by ever larger and larger corporations, with its limited budget, status as an independent film, and its reliance on word of mouth and social media for advertising. Especially in the present, there would seem to be few examples of a film whose success was achieved in this way, whether in Hong Kong or globally.

It remains to be seen if the film will linger beyond the anxieties of the present political climate in Hong Kong, and be remembered its own right in that way. But perhaps, then, it actually is that Ten Years pioneers a new sort of film and a new direction for Hong Kong film.

Still from “Extras”. Photo credit: Ten Years

Still from “Extras”. Photo credit: Ten Years Still from “Extras”. Photo credit: Ten Years

Still from “Extras”. Photo credit: Ten Years Still from “Season of the End”. Photo credit: Ten Years

Still from “Season of the End”. Photo credit: Ten Years Still from “Dialect”. Photo credit: Ten Years

Still from “Dialect”. Photo credit: Ten Years Still from “Dialect”. Photo credit: Ten Years

Still from “Dialect”. Photo credit: Ten Years Still from “Self-Immolator”. Photo credit: Ten Years

Still from “Self-Immolator”. Photo credit: Ten Years Still from “Self-Immolator.” Photo credit: Ten Years

Still from “Self-Immolator.” Photo credit: Ten Years Still from “Local Egg”. Photo credit: Ten Years

Still from “Local Egg”. Photo credit: Ten Years Still from “Local Egg.” Photo credit: Ten Years

Still from “Local Egg.” Photo credit: Ten Years Title card with Ten Years’ win on it. Photo credit: Reuters

Title card with Ten Years’ win on it. Photo credit: Reuters Film poster for Ten Years. Photo credit: Ten Years

Film poster for Ten Years. Photo credit: Ten Years