by Brian Hioe

語言:

English

Photo Credit: Enbion Micah Aan

AS NOTED in a recent LA Times article, probably one of the stranger afterlives of the Peter Liang case would be the case having taken on a life of its own in China. For one, Chinese social media platform Wechat was used, in part, to coordinate pro-Liang protests in America from China itself. Obviously, the partial coordination of protests in one country from another country is quite unusual, and probably a testament to the influence of social media in the Internet age. This occurred via an Wechat account titled “Civilrights”.

But it also is that Chinese state media has jumped onto the issue, with sympathetic articles about pro-Liang protests taking place in the People’s Daily, Xinhua News, and the Global Times, particularly the latter two. Chinese state media has quite unanimously used the Peter Liang case to make a point about discrimination against Chinese in America and taken the line that Liang is a scapegoat and that he should be let off, because white officers who have committed the same crimes had been let off in the past.

This would largely be the line taken by pro-Liang demonstrators in the US. In some cases, it appears information in Chinese state media was sourced from the “Civilrights” Wechat, with artificially inflated numbers for pro-Liang demonstrations. The “Civilrights” Wechat account claimed that there were 50,000 demonstrators in New York City, for example, when the actual amount was closer to 10,000. Xinhua would follow in claiming 50,000 demonstrators in New York. Chinese state media has also consistently cited the same cases of white officers let off for similar incidents that have been commonly cited as examples by pro-Liang demonstrators.

The Depiction of the Liang Case in Chinese State Media

WHY WOULD Chinese state media take a pro-Liang line, then? The answer probably lay in a desire to take the US down a peg, given the geopolitical tension which exists between the US and China as competing world superpowers. China quite often likes to claim that the US is rife with internal problems which it should take care of first before it arrogantly tries to criticize countries such as China.

Racial issues in the US is a popular target of China with the claim, for example, that the US should not criticize China’s treatment of ethnic minorities in outer China if it has racial tensions that boil over in Ferguson, Missouri and other locations. Interestingly, we may note that Chinese state media seems to have more sympathetic to Black Lives Matter movement before the Peter Liang case led to the involvement of ethnic Chinese, however. The consideration behind the switch in support may be considerations of whether siding Chinese or with blacks would be more eroding of American credibility.

Of course, such comparisons are really just China’s attempts to deflect attentions from ethnic policies that border on apartheid or arguably might even be understood as a mild form of ethnic cleansing. If there is, in fact, problems of systemic police violence against blacks in America, this is entirely different from China, in which police violence is not only used to put down ethnic minorities, but ethnic minorities are not permitted to travel in the country and the Chinese state offers money for intermarriage between Han and ethnic minority individuals in attempt to breed ethnic minorities out of existence through Han assimilation.

At the same time, though China tries to take the US down a peg in order to deflect attention from its own action, China sometimes will actually sometimes cite the US as an example of why its actions are justified. In such cases, rather than suggest the hypocrisy of the US in criticizing China for something it also is guilty of, the claim is that if the US does something, China should be allowed to do it as well.

Sometimes this is in regards to policing or military actions, claiming that if police in the US carry out certain actions, Chinese police should not be criticized for doing the same. China claims that its attempt to put down dissidence in outer Chinese regions is no different from the American War on Terror, for example.

A “Liberal” Undercurrent to Pro-Liang Protests?

WE MIGHT ALSO situate responses to the Peter Liang case in China in relation to the political tendencies that exist internally in China. Many have characterized post-Deng politics in China, particularly in the political atmosphere after Tiananmen Square in the 1990s, as the struggle between the “New Left” and “Liberals.” The “Liberals”, though perhaps closer to what are termed neoconservatives in other parts of the world, call for China to open itself to further free market reforms and suggest that China should imitate American-style democracy and civil life, though leaning much more towards American conservatism in this. On the other hand, the “New Left”, containing strands of sympathy or nostalgia for Maoism, argues against the abandonment of socialist principles and attempts to update Maoism through the incorporation of poststructuralist and postcolonial theory, though still problematic on the basis of its Chinese nationalism and its apologia for Chinese imperialism under anti-capitalist auspices.

An earlier pro-Liang protest which took place in April of last year. Photo credit: Enbion Micah Aan

An earlier pro-Liang protest which took place in April of last year. Photo credit: Enbion Micah Aan

The political discourse of Peter Liang supporters is remarkably similar to that of the Liberals in China. Though channeling an undercurrent of Chinese nationalism, pro-Liang protests have hewed to American civil discourse in claiming to be a movement in the vein of the American civil rights movement. Pro-Liang protests have also claimed a faith in the American political system highly reminiscent of the Chinese Liberals’ adulation of the American political model. Indeed, the Liberals (although this is also true of the Chinese New Left) have generally studied abroad in or otherwise had contact America before, which fits what is known about some of some of the China-based organizers of pro-Liang protests who are based out of China.

The Ghost of Past Maoist Solidarity with the Black Liberation Movement

BUT THE IRONY of Chinese state media championing pro-Liang protests is that it is actually the New Left who are in power currently under Chinese president Xi Jinping. Under Xi Jinping’s rule, although it first looked as if Xi would side the Liberals during his purge of New Left idol Bo Xilai, Xi eventually swung towards policies called for by the New Left and by neo-Maoist strands, leading to the renewed wave of Chinese nationalism we see in the present.

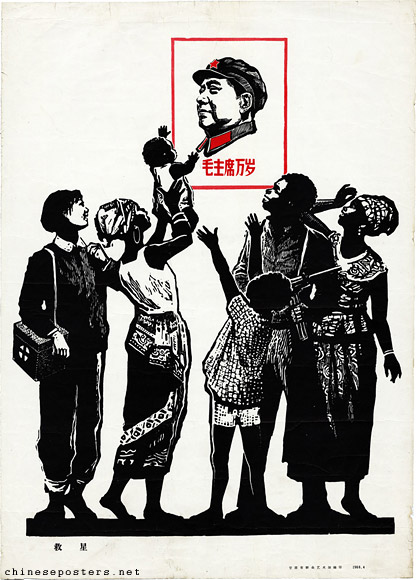

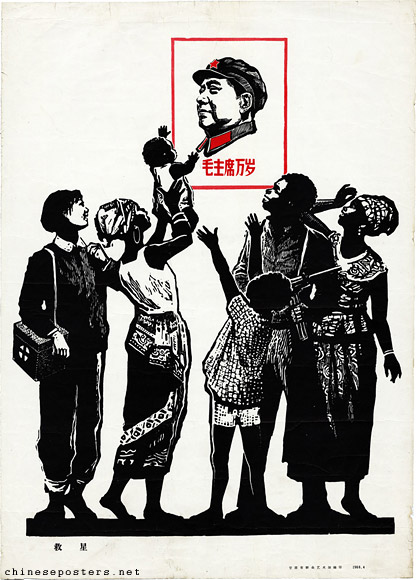

Some New Left strains closer in touch with American Leftists have, in fact, criticized pro-Liang protests. Yet in the responses of Chinese state media, we see the ghost of Maoist calls for solidarity with the black liberation movement of 1960s and 1970s. China today likes to play up the history of Maoist solidarity with third world liberation movements to justify its economic overtures to Africa, even when this has been criticized within Africa as a form of neocolonialism or neo-imperialism. But in a case as the Peter Liang case, the Chinese states sides with Peter Liang on the basis of Chinese ethnic nationalism.

Chinese propaganda poster showing a group black men and women and one Chinese woman on the left venerating a picture of Mao. Photo credit: Chineseposters.net

Chinese propaganda poster showing a group black men and women and one Chinese woman on the left venerating a picture of Mao. Photo credit: Chineseposters.net

The call for supporting Peter Liang because he is over Chinese descent overrides any consideration of systemic violence against blacks in the US or solidarity with other oppressed peoples. Obviously, only the deluded should view China as a socialist revolutionary state nowadays, although there are still some individuals who do so through a combination of ignorance or deliberately shutting one’s eyes.

Peter Liang in China

THESE ARE JUST some of the unusual afterlives of the Peter Liang case in China. In truth, it may be premature to see these as “afterlives,” seeing Liang is expected to appeal, meaning the case is not over yet. But the appropriations and the discursive deployments of the case in China are illustrative about China’s relation to American politics as well as the internal political tendencies that exist within China.

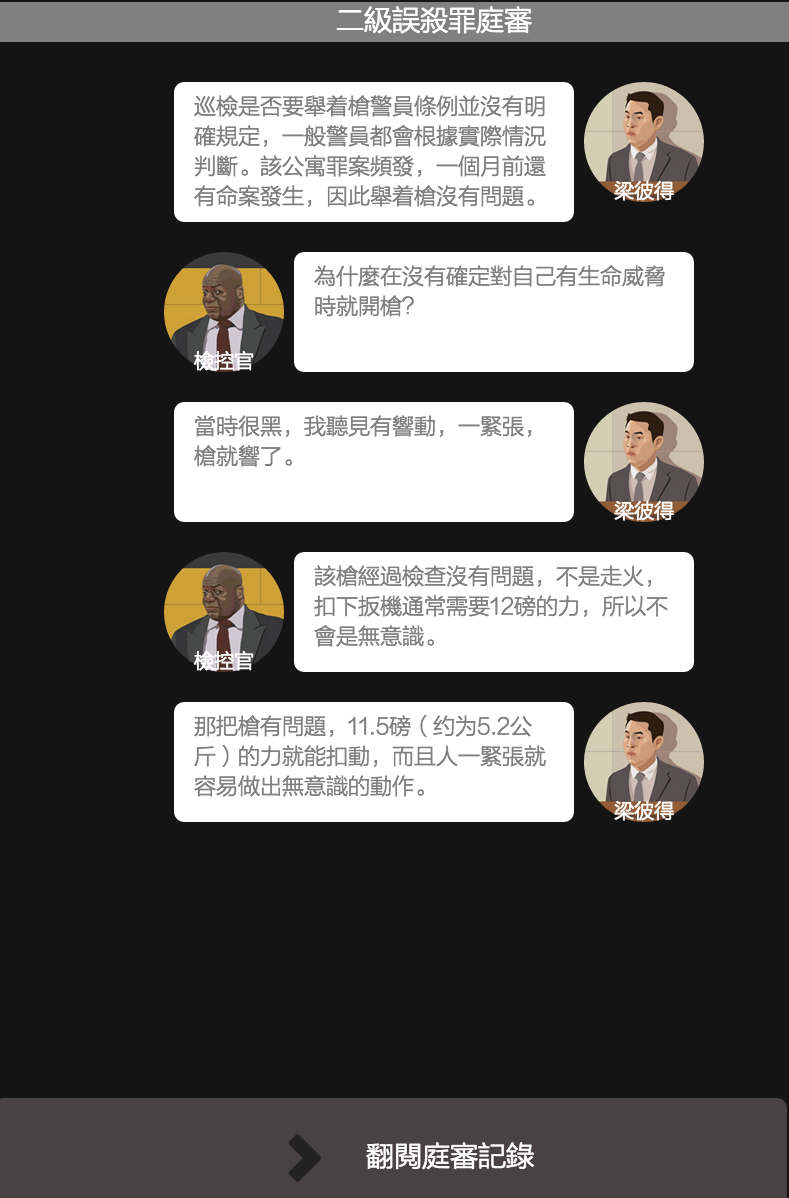

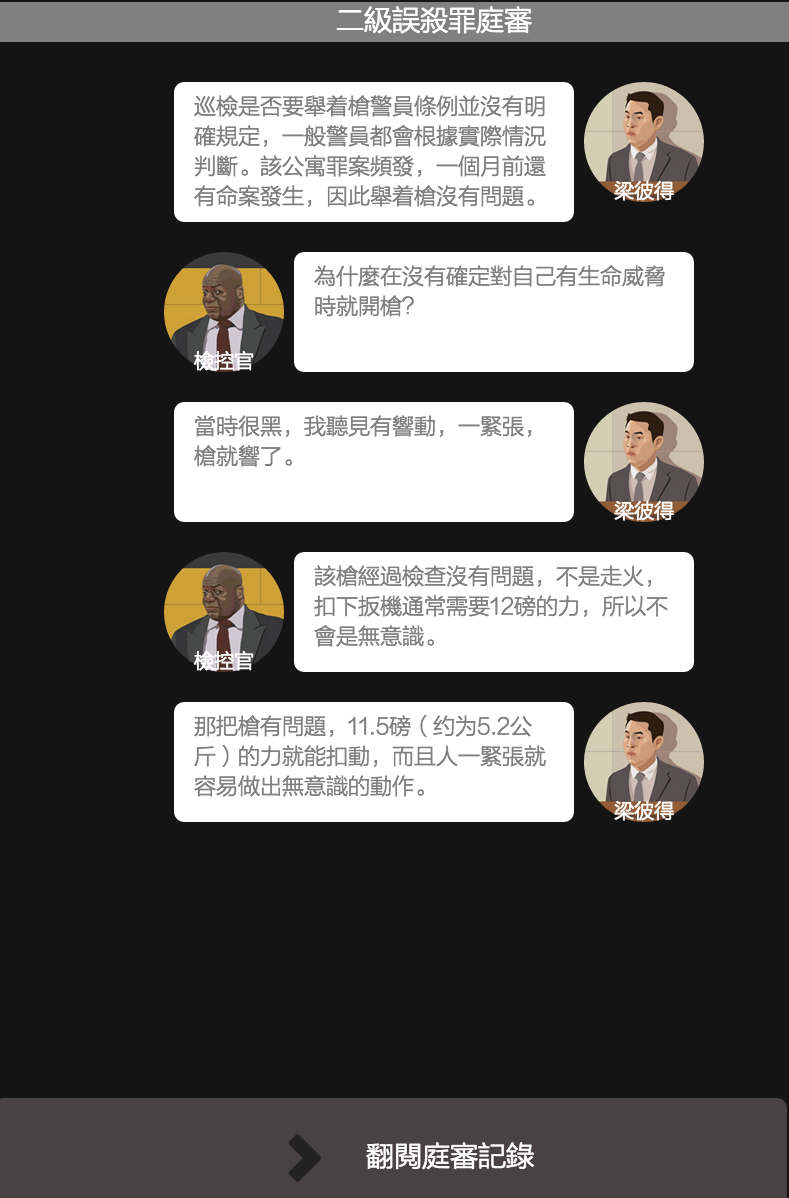

Outside of China, there has also been some interest in the case from Hong Kong and Taiwan, maybe moreso the former than the latter. This may be because Liang was born in Hong Kong, but immigrated to the United States at an early age. Hong Kong-based Initium Media would create an interactive animated game about the trial, for example. The game makes some interesting stylistic choices by making Liang’s animated avatar interact with a black bailiff, rather than the Korean judge who oversaw the case though he also appears in the animation—meaning that the developers were aware of that fact that the judge on the Liang case was Korean. However, the game does not slant particularly to favor Liang and, perhaps surprisingly, the survey conducted at the end of the game indicates that the majority of players favor the conviction against Liang once they have played through the game.

Notably, though the Peter Liang case is one which concerns Asian-American groups in the United States, having prompted response from far more than Chinese-American groups, we do not see reverberations about the case from other Asian countries outside of China and Sinophone countries and territories.

An image from Initium Media’s interactive online game about the Peter Liang case. Photo credit: Initium Lab

An image from Initium Media’s interactive online game about the Peter Liang case. Photo credit: Initium Lab

Of East Asian countries, there has nothing comparable to the interest in the case we see from China in South Korea or Japan, for example, or even in Singapore, whose majority population is ethnically Han Chinese. Probably this is illustrative of how it has specifically been China which has been concerned with the Liang case, or suggests that Chinese nationalistic sentiments may have a key role in interest in the Liang case. But we will also see as to future reactions to subsequent case developments in China and elsewhere.

An earlier pro-Liang protest which took place in April of last year. Photo credit: Enbion Micah Aan

An earlier pro-Liang protest which took place in April of last year. Photo credit: Enbion Micah Aan Chinese propaganda poster showing a group black men and women and one Chinese woman on the left venerating a picture of Mao. Photo credit: Chineseposters.net

Chinese propaganda poster showing a group black men and women and one Chinese woman on the left venerating a picture of Mao. Photo credit: Chineseposters.net An image from Initium Media’s interactive online game about the Peter Liang case. Photo credit: Initium Lab

An image from Initium Media’s interactive online game about the Peter Liang case. Photo credit: Initium Lab