What Can Youth Movements Learn From Each Other?

by Brian Hioe

語言:

English

Photo Credit: 湯惠芸/VOA/CC

Hong Kong’s Young Entering Electoral Politics?

FOR THOSE of us who lived through the Sunflower Movement and its aftermath, Joshua Wong’s announcement of his intent to run for legislator in Hong Kong would strike as eerily familiar. Wong’s intent to run, of course, draws parallels to Sunflower Movement leader Chen Wei-Ting’s brief campaign to run as legislator of his native Miaoli during late 2014 through by-election. Chen, however, would later withdraw because of a scandal regarding past acts of sexual harassment that emerged during the course of his campaign which had not come to light during the Sunflower Movement itself.

Wong faces the uphill challenge of that he is not actually old enough to run as legislator. As a result, Wong is calling for a lowering of the age limit required for electoral candidates. Once again we see shades of Taiwan. Shortly before 2014 elections, Taiwan saw a campaign to lower the voting age from 20 to 18, with young people calling attention to the fact that they could serve in the military and drink legally, but were not allowed to vote. Though ultimately unsuccessful, in the course of this campaign, young people called attention to the fact that in order to maintain power, the KMT would attempt to keep Taiwan’s young from voting given that the generational shift in Taiwanese identity politics would inevitably lead to young people voting against the KMT.

Chen during last year’s Legislative Yuan occupation. Photo credit: Wang Ying-hao

Chen during last year’s Legislative Yuan occupation. Photo credit: Wang Ying-hao

Of course, if it is that Taiwan and Hong Kong strike as highly reminiscent of each other by way of the youth uprisings which have occurred since last year’s Sunflower Movement and Umbrella Movement, we point to that parallels between Taiwan and Hong Kong are far from coincidence. Certainly, it is true that Taiwan’s Sunflower Movement had some influence on the Umbrella Movement; I myself, for example, met a number of individuals from Hong Kong who visited Taiwan in the aftermath of the Sunflower Movement who would later become participants within the Umbrella Movement.

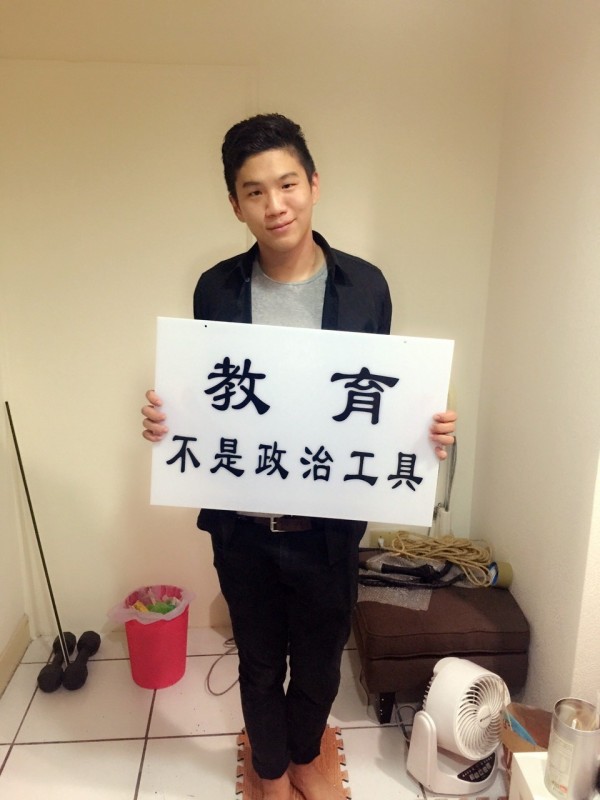

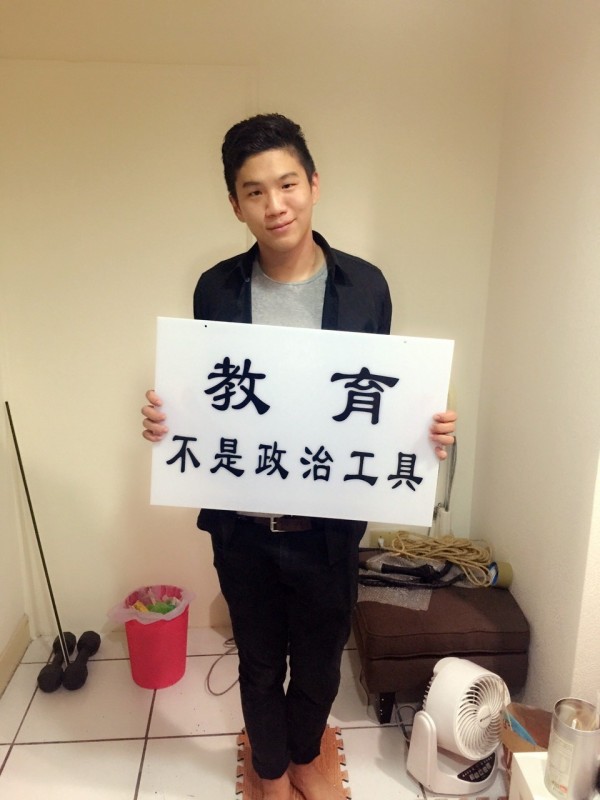

And we might more broadly point to that the Umbrella Movement would come to influence Taiwanese activist politics afterwards. One thinks of the weeklong occupation of the Ministry of Education by high school students in protest of pro-China textbook revisions put in by the KMT. In Hong Kong, Joshua Wong’s Scholarism group which would be a crucial actor during the Umbrella Movement was originally founded in opposition to pro-China textbook revisions. Indeed, though in the case of the Taiwanese Ministry of Education occupation, there were few indications that there was any direct contact by high school occupiers with their Hong Kong counterparts, it was that Hong Kong had been an inspiration. Very likely, we can point to a cycle by which Taiwanese activism is coming to influence Hong Kong activism and Hong Kong activism influencing Taiwanese activism, as a reciprocal process.

However, there remain other parallels between Taiwanese activist politics and Hong Kong activist politics which do not seem to stem from the direct influence of one locality on another. To begin with, there would be significant similarity in the way that student activists have been understood within public discourse, and social responses to the actions of student activists in Taiwan and Hong Kong are strikingly. In this light, we may perhaps point to the existence of structural parallels between Taiwan and Hong Kong as they engender these similar responses.

The Cases of Joshua Wong and Chen Wei-Ting

In order to quickly grasp how much an outside observer understands the internal dynamics of Taiwanese or Hong Kong activist politics in discussion, raising the figures of Joshua Wong or Chen Wei-Ting is often a quick litmus test. For outside observers, Wong and Chen remain the heroes of yesteryear as the unequivocal protagonists of the Umbrella and Sunflower Movement. But both have seen scandals since. From left to right, Chu Yiu-Ming, Benny Tai, and Chan Kin-Man. Photo credit: VOA

From left to right, Chu Yiu-Ming, Benny Tai, and Chan Kin-Man. Photo credit: VOA

In the case of Wong, although before the outbreak of the Umbrella Movement, Wong and Scholarism were seen as a more radical force than the more moderate, even overly accommodating Occupy Central as led by the triumvirate of Benny Tai, Chan Kin-Man, and Chu Yiu-Ming—although since then, Tai has notably come to entirely overshadow the other two. Scholarism was at that time much more unequivocally supported by the politically conscious, where there was much more of a divide about Occupy Central.

Wong would become more and more controversial, given that while he and Scholarism had been previously known for willing to take radical action but during the course of the Umbrella Movement, Wong would side with the politically moderate forces of Occupy Central that sought at times to rein in what they saw as too radical elements of the movement. After the end of the Umbrella Movement, with localist sentiment about a Hong Kongese versus Chinese identity on the rise, Wong would also see criticism for claiming that he did not think that the current movement in Hong Kong should separate itself from the democracy movement in China. Wong has come under fire for not siding with the view that Hong Kong should radical divorce itself from the mainland. In this way, Wong is seen as too moderate.

On the contrary, although it is true that Chen Wei-Ting has not been forced to walk back any particular political claims, Chen’s brief campaign run for legislator of Miaoli came to an end after it was revealed that Chen had had an incident in high school in which he groped a woman on a bus. After other sexual harassment allegations came to light, Chen resigned.

To be sure, Chen had been a divisive figure during the Sunflower Movement itself, as one of the three most visible leaders of the occupiers within the Legislative Yuan, the other two being Lin Fei-Fan and then-Academica Sinica professor and current NPP politician Huang Kuo-Chang. Chen was criticized by some for being overly radical and others for being too moderate, still others taking issue with that decision-making for the movement as a whole had been centralized within the hands of a small group of people. But the tainting of Chen Wei-Ting’s reputation in the sphere of Taiwanese activist politics did not take place until after the sexual harassment scandal. Although present, for example, on the first night of the Ministry of Education occupation as an observer on the sidelines as encountered by myself, Chen has largely kept out of the limelight since.

Demonstrators storming the courtyard of the Taiwanese Ministry of Education on the night of July 30th. Photo credit: Brian Hioe

Demonstrators storming the courtyard of the Taiwanese Ministry of Education on the night of July 30th. Photo credit: Brian Hioe

With the case of Wong and Chen, what we can point to in Hong Kong and Taiwan is the way in which a single figure has become an object of adulation by mainstream society out of a social movement. In such cases, we can point to a form of personalist politics in which a single figure is elevated to the attention of mainstream society by the media spotlight and heroicized in that way. But the downfall of Chen happened, too, on the basis of that media was equally quick to turn on him.

Even if it is true that Wong has seen no decisive incident in which led to a downfall from the media spotlight, it is true that the luster of untainted heroicism which he once had in Hong Kong has faded. It remains to be seen whether Wong would, in fact, see any scandal which would be seized upon by the media that would lead to a downfall similar to that of Chen. However, can we point to a systematic parallel behind the heroicization of social movement leaders, as we see in the cases of Chen and Wong?

From Self-Sacrificing Heroes to Social Miscreants

As many have pointed to, in the cases of Taiwan and Hong Kong, students took the forefront of the Sunflower and Umbrella Movements because of the high place students occupied in the “Confucian” worldview of both societies. Students were seen as morally pure and taking action for the sake of their sense of the social good, at risk of self-sacrifice. Whether “Confucian” or not in origin, with this sort of social attitude we can see similar patterns of understandings of students in Sinophone societies. Indeed, we see generally similar attitudes about students in regards to how Chinese Tiananmen Square occupiers were understood in 1989 or how Taiwanese Wild Lily occupiers were understood in 1990.

The attempt to storm of the Executive Yuan which took place on March 23rd, 2014. Photo credit: Brian Hioe

The attempt to storm of the Executive Yuan which took place on March 23rd, 2014. Photo credit: Brian Hioe

It was such that in the Sunflower and Umbrella Movements that students would come to a position of prominence and their actions would come to receive the attention of society at large. And so we can probably point to a generally shared phenomenon behind the rise of student leaders such as Wong or Chen to public prominence.

The flip side of this, however, is when society turns on the role of students as moral exemplars and re-labels them unruly disruptors of social order. We saw this in Taiwan, for example, when students attempted to occupy the Executive Yuan, the executive branch of government, twelve days after the Legislative Yuan occupation. Because the occupation attempt had been clearly premeditated and the Legislative Yuan had not been, and because the occupation attempt involved the destruction of some pieces of public property, the public turned on students and condemned them as miscreants instead of seeing them as morally pure saviors of society.

Lin Kuanhua

Lin Kuanhua

This can have consequences. This past summer’s Ministry of Education occupation was prompted by the suicide of student leader Lin Kuanhua which took place after Lin’s arrest on a preceding attempt to occupy the Ministry of Education on July 23rd. Although it may have been any of a number of issues which led to Lin’s suicide, Lin was reportedly told after his arrest by authorities that he would have no future, that he would never be able to find a job or place in society because of his arrest record. Told that he would experience “social death” through his activism, it may have been that this led to Lin’s actual death. Whether in the case of Lin or the attempted Executive Yuan occupation, one suspects sometimes that the society which valuates and holds the young so highly when they take what they believe is right into their own hands can turn around equally as fast and judge them to be unredeemable social miscreants. And sometimes it is that a society devours its young.

Conclusion: What Can Youth Movements Learn From Each Other?

With Wong, we will see as to how his plans to run for legislator in Hong Kong fares. Certainly, if compared to Chen Wei-Ting, Wong has not seen any singular event discrediting of him, it is definitely true that his reputation is not as it was before the Umbrella Movement. Yet we can generally point to structural parallels in Hong Kong and Taiwan by which student leaders are elevated to a position in the media spotlight and can sometimes fall from grace, as well as the means by which students can be seen as morally pure and self-sacrificing for the good of society one moment then condemned as social miscreants the next.

Where do such parallels originate? Again, general similarities in Sinophone cultures? “Confucian” social morality? It is hard to say. Actually, it probably does not accomplish very much to try to find any singular cause. However, going forward, where drawing parallels and comparisons may be useful, it is to allow Hong Kong activists to better understand themselves through comparison to Taiwan and Taiwanese activists to better understand themselves through comparison to Hong Kong activists. If there seems to be a vague sense of solidarity between young activists in both locations out of a sense of shared cause, perhaps a general sense of solidarity can be put to more productive use in attempting to learn from each other—not only through direct sharing of skills—but also on the basis of that it is structural similarities in each society give rise to similar phenomenon.