by Brian Hioe

語言:

English /// 中文

Photo Credit: qbix08/Flickr/CC

Looking Back on A Year of Protest

FOR A CHINA forever on the guard against the specter of “separatism,” the future does not appear to be a good one. It is probable that 2016 elections in Taiwan will be one in which Tsai Ing-Wen, candidate of the DPP and not the pro-China KMT, will be victorious. And Taiwanese civil society will remain active, with the recent formation of a number of new third parties originating out of Taiwanese civil society. In August we saw high school students occupy the Ministry of Education of education after the suicide of student activist, Lin Kuanhua. As 2016 elections approach and political tensions heighten, we can very probably expect further outbreaks of protest, although it remains to be seen whether anything as large as the Sunflower Movement would emerge, the Ministry of Education occupation never being as large in numbers or scale as last year’s Legislative Yuan occupation.

On the other hand, one year after the Umbrella Movement which shook the world in fall of 2014, it does appear that there is greater disorder for Hong Kong with the possibility of a second Umbrella Movement appearing to be unlikely at present. In late June, Hong Kong lawmakers voted down a reform proposal by China, with 28 pan-democratic lawmakers out of 70 lawmakers voting down the proposal, 8 refusing, and a number of pro-China lawmakers attempting to stall the vote through a walkout but this failing when the vote happened anyway, despite their absence.

This was not unexpected, and despite that pan-democratic lawmakers have seen heavy criticism by Umbrella Movement activists themselves in recent months for being overly moderate, it is also true that the division of lawmakers along pro-Beijing and pan-democratic lines leads to an impasse in the current situation in Hong Kong. Beijing will no doubt continue to seek to diminish Hong Kong’s relative autonomy relative to mainland China, but it is funny to note that while it might attempt to do so through the auspices of democracy in order to minimize resistance, it is not doing a terribly good job. Hong Kong Chief Executive C.Y. Leung, much reviled during the Umbrella Movement, recently caused a public incident by declaring the “transcendent” authority of his position. And although many commemorative activities were held in Hong Kong to mark the one year anniversary of the Umbrella Movement, we did not see any significant outbreak of protests.

But what, then, for China in the near future? As part of recent moves at centralizing its authority and expanding regional power, China wishes to firmly consolidate its rule over Hong Kong, and at least in public rhetoric, seeks to resolve the longstanding Taiwan question as soon as possible. This will not be easy for China.

Similarities Between Taiwan and Hong Kong Protest Culture

PERHAPS WE CAN say that over one year after the Sunflower Movement and the Umbrella Movement, the battlefield has shifted to electoral grounds in Taiwan and Hong Kong. There is no surprise there, where the outbreak of social movements tend to be short but explosive, and usually lead to a loss of momentum afterwards. In the cases of both Taiwan and Hong Kong, in the absence of the outbreak of subsequent social movements, momentum shifts towards electoral politics. The August Ministry of Education occupation in Taiwan saw an interruption of the electoral politics which had set in for much of the year after the Sunflower Movement, but after the end of the election, we largely saw a return to normal electoral politics.

As evidenced in the Sunflower Movement, the Umbrella Movement, and the August Ministry of Education occupation, both Hong Kong and Taiwan share a similar protest culture. For one, with both Taiwan and Hong Kong, one is struck by the key role of students. Students in societies with traditionally Confucian value systems as Hong Kong have the social position whereby they can stand for what is “pure” and take action in the name of realizing a more just social order in name of that purity. So then, do students have a role in society which is quite particular to the role they play in outbreaks of social unrest in Asia as the Umbrella Revolution, the Sunflower Movement, the Ministry of Education occupation, or even the present movement in Japan against the reinterpretation Article 9 of the Japanese constitution. But combined with that youth are globally being put into the spotlight whereas protest across the world is concerned with the generation of an increasing amount of young in social conditions less than conducive to their livelihood, Asia’s youth are driven to the forefront of protest movements.

Taiwanese president Ma Ying-Jeou depicted as a monstrous “titan” from popular anime Shingeki No Kyojin, with Sunflower Movement leaders depicted as protagonists of the show. Photo credit: 大牙齦劇團

Taiwanese president Ma Ying-Jeou depicted as a monstrous “titan” from popular anime Shingeki No Kyojin, with Sunflower Movement leaders depicted as protagonists of the show. Photo credit: 大牙齦劇團

Similarly, it says something about the hyper-conscious nature of contemporary protest to the degree that both Taiwan and Hong Kong consciously sought out emblems and symbols and adopted a set of protest aesthetics regarding these adopted symbols. In the case of the Sunflower Movement, sunflowers were distributed in the courtyard of the Legislative Yuan on the night of the initial occupation, and subsequently adopted as the symbol of the movement. The Umbrella Revolution’s name comes from the use of umbrellas by protestors to defend against the firing of tear gas by Hong Kong police. One can speculate as to that both movements sought to brand themselves, given that information circulates most easily through brand names and recognizable imagery in the age of social media. And so both movements subsequently saw an explosion of sunflower or umbrella-themed art.

In pointing to similarities in protest artwork, we might also be keenly aware of the significant influence of Japanese pop culture on the artworks of the Sunflower Movement and Umbrella Movement. Where Hong Kong and Taiwan saw an explosion of economic development in the 1970s and 1980s as two of the “East Asian Tigers” and subsequent building of economic trade ties with other East Asian countries as Japan, Korea, Singapore, and others the result was the importation of Japanese pop culture which allowed for the diffusion of Japanese cultural influence.

This was a product of the earlier Japanese economic miracle having provided the economic structures for the diffusion of Japanese cultural commodities to later developing East Asian economies. But where Japan, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and other East Asian tigers shared similar economic development models, the result was a similarity in lifestyle between these countries. This allowed for the diffusion of Japanese cultural products where depictions of Japanese daily life and cultural values as founded upon a culture of middle class consumption, resonated closely enough with the lifestyles of middle class individuals living in Hong Kong and Taiwan that they would find widespread circulation. Certainly, this is another indication of that the socioeconomic similarity of Hong Kong and Taiwan is probably the reason as to why Hong Kong and Taiwan would develop similar protest cultures.

The 《超級香港故事》(“Super Hong Kong Story”) comic by by 活人拳 which became a viral hit during the Umbrella Movement (left) with a still from Japanese anime G Gundam (right). Photo credit: 活人拳

The 《超級香港故事》(“Super Hong Kong Story”) comic by by 活人拳 which became a viral hit during the Umbrella Movement (left) with a still from Japanese anime G Gundam (right). Photo credit: 活人拳

Whereas international media made much of Hong Kong’s Umbrella Revolution as the “most polite protestors ever” during the Umbrella Movement in picking up trash and maintaining the orderliness of their occupation site, one can point to that that the Sunflower Movement protestors were also quite surprisingly orderly in religiously cleaning the site around the Legislative Yuan. Certainly, some journalists at the time of the Umbrella Movement saw evidence that Hong Kong protestors have looked towards Taiwanese activists in structuring their own movement in matters of internal organization, and it is also true that a number of activists later involved in the Umbrella Movement actually did come to Taiwan after the Sunflower Movement in order to learn from Sunflower Movement activists, I myself meeting several such individuals in the aftermath of the Sunflower Movement.

Yet rather than point to direct influence between Taiwan and Hong Kong, one wonders whether this misses something about contemporary protest culture worldwide and how a global set of socioeconomic conditions facing young people has led to protest movements across the world that share certain characteristics. One remembers how Occupy Wall Street, coming out of the tradition of global summit-hopping protests such as protests against the G-8 or IMF conferences from the 1990s, rapidly developed a self-organized structure to clean the occupation site of Zuccotti Park on a regular basis—although this may not have ever been terribly effective in keeping Zuccotti Park clean.

But the longer a protest movement which might be disruptive of people’s everyday lives, the more public dissatisfaction against it grows. While the Sunflower Movement’s occupation of the area surrounding the Legislative Yuan was far removed enough from daily life in Taipei for this to never become a problem, to the extent that the Hong Kong occupation involves the occupation of parts of Hong Kong integral to people’s daily living, this became where animosity surged up against the Umbrella Movement occupations for disrupting everyday life in certain areas of Hong Kong.

The Taiwanese Legislative Yuan occupation was remarkable for its length, given that it lasted twenty four days. But, in the end, it terminated before factional conflict became too damaging to the movement as a whole, and before the movement began to grate on lives of everyday Taiwanese. We can say much the same with the Ministry of Education occupation, although it was put to an end by approaching typhoon. On the contrary, by the time the Umbrella Movement ended, there was significant backlash against the movement for dragging on so long, and the movement had begun fragmenting violently, with its leaders continuing to apologize in the present for not calling it off sooner. We see continued fragmentation in the present.

Differences Between Hong Kong and Taiwan Regarding Sense of Identity

BUT IF WE may point to where the terrain of contestation has now shifted towards electoral politics, if we are point to an origin of the differences between how the Sunflower Movement and how the Umbrella Movement, this may lie in the fundamental differences between Hong Kong and Taiwan. The turn towards electoral politics is also quite different in the relation to civil society and activist politics between Taiwan and Hong Kong.

In both Taiwan and Hong Kong, civil society comes into conflict with lawmakers, and lawmakers tend to be more conservative than civil society, or come with a set of interests that conflict with civil society. But actually, if we are to venture a comparison between Taiwanese civil society and groups in Hong Kong, there has been greater tension between activist groups in Hong Kong and pan-democratic lawmakers. Where it is also true that there is some tension between Taiwanese civil society groups and the Taiwanese Democratic Progressive Party, Taiwanese civil society groups have, on the whole, been rather supportive of the Tsai Ing-Wen presidential candidacy if they are usually also critical of the Democratic Progressive Party as a whole.

This may also reflect the multipolar nature of electoral politics in Hong Kong, where in Taiwan despite the rise of new third parties, political power still divides largely between the pan-blue and pan-green camps. Within new third parties, the so-called “Third Force,” it is a divisive issue as to whether one should cooperate with the DPP or not for local elections and as to whether one should soften one’s ideological line in order to appeal to “light blue” voters who supported the KMT in the past. It is a further question as to whether untested Third Force parties will find success in upcoming elections, given that Third Force parties may not cooperate among themselves, and may not be able to win unless they come together in alliance. However, despite claims to try and break out of the Blue-Green deadlock of Taiwanese politics, it is probably true that Third Force parties as a whole still operate within the rubric of the pan-Green alliance.

Tsai Ing-Wen at a recent campaign rally. Photo credit:蔡英文 Tsai Ing-wen Facebook Page

Tsai Ing-Wen at a recent campaign rally. Photo credit:蔡英文 Tsai Ing-wen Facebook Page

But there are also strong differences in the relation to China between Taiwan and Hong Kong. Since the end of the Umbrella Movement we have seen an outbreak of anti-Chinese sentiment, for example, the rise of localist/nativist sentiment on a level never before seen, and the emergence of the previously marginal political platform of Hong Kong independence as a significant platform which is now advocated by groups where it was previously a radical, marginal position. To begin with, it is vaguely surprising that Hong Kong independence was not previously a political position which had any widespread circulation given Hong Kong’s unavoidable position of political subjugation to China; by contrast, the decades old Taiwanese independence movement goes on despite the de facto independence of Taiwan to China.

After the Sunflower Movement, there was some controversy over a Chinese student studying in Taiwan who ran for a student office position after previously expressing support for the Sunflower Movement and some protest regarding Chinese tourist groups in Kaohsiung. But it is probably also true to say that anti-Chinese sentiment directly targeting mainland Chinese on racial, ethnic, or sub-ethnic grounds is nowhere as widespread in Taiwan as it is Hong Kong.

Hong Kongers have a longstanding reputation disliking mainland Chinese. Hong Kongers’ antagonism towards Chinese is not only in regards to the Chinese encroachment upon Hong Kong’s sovereignty, but also lifestyle. Stories of Chinese tourists swarming into and then blatantly disregarding Hong Kong social custom, most infamously in incidents of public defecation, contribute to an image of mainland Chinese are being in some sense uncivilized. One can point to a clear economic element to this, whereas the Chinese poor recently elevated to a socioeconomic status which allows for travel to Hong Kong are not so habituated to first-world social mores.

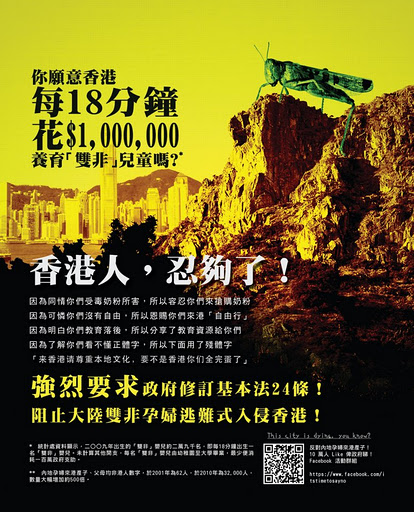

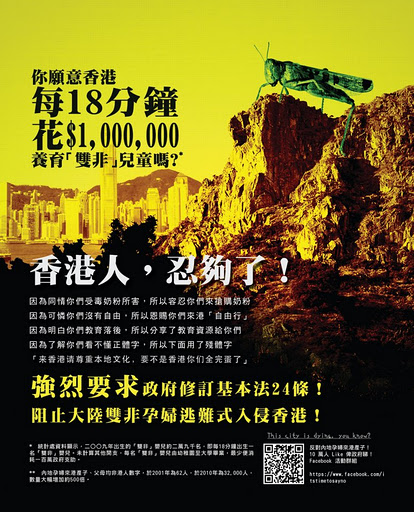

The infamous “locust ad” which appeared in the Apple Daily. Photo credit: Apple Daily

The infamous “locust ad” which appeared in the Apple Daily. Photo credit: Apple Daily

Likewise, with the migration of Chinese into Hong Kong with the easing of border restrictions, stories are circulated of Chinese entering Hong Kong to give birth only for the sake of their children being able to enjoy Hong Kong’s economic benefits. It is true that 40,000 mainland Chinese mothers gave birth in Hong Kong hospitals in 2011, for example. And so Chinese appear parasitic to Hong Kongers; infamously, an ad in the Apple Daily depicted Chinese as locusts. Smugglers operating across the mainland China-Hong Kong border also at times become the target of hostility, where they sometimes skirt the fringes of the law to Hong Kong’s economic detriment. Hostility towards mainland Chinese on this basis has heightened since the Umbrella Movement. The most recent prominent examples has been a set of images circulated on social media which seek to point towards some essentialist difference between Chinese and residents of Hong Kong in regards to manners and custom, these images having circulated widely on the basis of being well-designed, but also having attracted controversy not only in regards to discriminatory sentiment towards Chinese.

Rising inequality within both Taiwan and Hong Kong has also sometimes been the product of Chinese influence. What has served to drive up real estate prices to be unaffordable in both Hong Kong and Taiwan has been the influx of Chinese business and economic interests, for example. Likewise, same stories about tourists largely circulate in Taiwan, which also sees an influx of Chinese tourists yearly, although there is far less Chinese migration. Yet Taiwan does not have a reputation for anti-Chinese sentiment the way that Hong Kong does. Why?

Namely, in both the Sunflower Movement and the Umbrella Movement, there was an internal enemy and an external enemy. In the Sunflower Movement, the internal enemy was the pro-China KMT, which undemocratically advanced policies aimed at facilitating the economic integration of Taiwan and China. The external enemy was, of course, the Chinese Communist Party. Likewise, in Hong Kong, the internal enemy was the Hong Kong government, which subjected protestors to police violence, and undemocratically aimed the facilitate the policies mandated by Beijing. The external enemy was, too, the CCP.

One of the viral images illustrating purported differences between Chinese and Hong Kongers. Photo credit: Local Studio HK (本土工作室)

One of the viral images illustrating purported differences between Chinese and Hong Kongers. Photo credit: Local Studio HK (本土工作室)

But Taiwan, unlike Hong Kong, is already constituted as an independent self-governing territory. Taiwan’s Sunflower Movement was vaguely defensive in nature of Taiwan’s already existing, if highly imperfect independence. If hostility towards Chinese is founded upon an sense of anxiety, Taiwanese drift far less towards anti-Chinese sentiment because of a less of a sense of anxiety about Taiwan’s already existing state of independence. Where Hong Kong is not independent, the sense of anxiety about China is more deeply set. So then is there is not only opposition to the Chinese government, but also to the Chinese themselves.

In at least Taiwan after the Sunflower Movement, with yearly Tiananmen Massacre commemoration activities, Taiwanese activists declared solidarity with Chinese democracy activists as they had in years prior—though stressing that Taiwan and China were separate, and that solidarity activities directed towards China were conducted by Taiwanese as a solidarity action towards their neighboring country. In Hong Kong, however, controversy ensued about whether residents of Hong Kong should commemorate the anniversary of the Tiananmen Square massacre, some arguing that residents of Hong Kong had not need to commemorate something that took place in a foreign territory. This is despite that historically and up to the present, Tiananmen Massacre commemoration activities in Taiwan have had small attendance. By contrast, in the past they tended very large in Hong Kong and, in fact, at times featured numbers of historical significance.

But we can perhaps point again to the growing strength of localism/nativism and a pro-independence movement in Hong Kong after the Umbrella Movement, where Taiwan already had a long-standing independence movement and a period in which ethno-nationalist sentiment ran high, before this was later replaced with a form of civic nationalism. Likewise, we can point to this being a simple matter of Taiwan’s greater geographic distance from China. Will activists in Taiwan and Hong Kong, then, draw lines in the sand between themselves and Chinese on exclusivist grounds in the future?

Demonstrators forcing their way into the Ministry of Education in Taiwan on July 30th. Photo credit: Brian Hioe

Demonstrators forcing their way into the Ministry of Education in Taiwan on July 30th. Photo credit: Brian Hioe

We will see as to what the future bodes. Against ethno-nationalism, however, it is refreshing to observe that the textbook protests which broke out, high school age student activists stressed that their point was not to emphasize a form of native Taiwanese history against the Chinese history that the KMT would attempt to put into place—but rather, that Taiwan needed history textbooks in which the history that was taught reflected Taiwan’s multi-ethnic nature, given the multi-ethnic nature of contemporary Taiwanese society and Taiwanese history.

Where Taiwan’s de facto sense of independence has allowed for some seventy odd years to meditate upon the meaning of the Taiwanese identity vis-a-vis China, the sense of confidence of Taiwanese about their Taiwanese identity as distinguished from a Chinese identity has had more time to be deeply thought out. This may, however, be because Taiwan is simply farther removed from China than Hong Kong both geographically and historically.

A Shared Nostalgia for the Colonial Past?

TO TURN TOWARDS questions of national identity, we can point to certain similarities between how Hong Kongers and Taiwanese conceive of their identity in relation to China. As Lin Fei-Fan of Sunflower Movement fame pointed out quite correctly in an article for The Diplomat, there certainly are historical resonances between Taiwan and Hong Kong. What Hong Kong and Taiwan share alike is the history of colonialism in which both were bifurcated from a mainland Chinese identity by virtue of colonialism. In the case of Hong Kong, this was of course the history of British colonialism from 1839 onwards, which only ended in 1997 with the return of Hong Kong sovereignty to China.

By contrast, Taiwan was colonized by the Japanese from 1895 to 1945, splitting it from mainland Chinese history. Taiwan was then “colonized” by the KMT after its defeat in China and retreat to Taiwan. Likewise, where Taiwan has further precedents for a split history from China dating to before Japanese colonialism beginning from the 1895 Treaty of Shimonoseki, western scholarship tends to date the split between Taiwan and China as occurring from the 1949 defeat of the KMT.

For both Hong Kong and Taiwan, it is of note that this colonial history is upheld in the present in order to justify claims that Hong Kong or Taiwan are not quintessentially Chinese. Hong Kong’s period of British colonialism has become mythicized to some extent, in regards to that the British introduced democratic reform into Hong Kong which subsequently repealed when Hong Kong fell to Chinese control, providing the grounds for the demand that Hong Kong had been promised long before and that China’s current actions are hypocritical. To some extent, Hong Kong’s British past has therefore become mythicized on the basis that the British understood Hong Kong as “ready” for democracy versus a greater China which apparently was not and so sought to introduce democracy into Hong Kong, despite the truth is that the British only introduced democratic elements of governance during the final administration of Hong Kong after so many decades of colonial administration as a way to save face and not come off as “abandoning” Hong Kong to autocratic China after the 1990 Tiananmen Square Massacre.

One can find parallel in that the period of Japanese colonial administration has also become mythologized in Taiwan, on the basis of that under Japanese rule, Japanese colonial administrators advanced assimilatory initiatives aimed at integrating educated Taiwanese into the fold of the Japanese colonial empire and were careful guardians of Taiwan’s natural resources. By contrast, after control of Taiwan fell to the KMT, the KMT treated Taiwanese as conquered subjects, having become corrupted by Japanese influence, as embodied in economic policies denigrating native Taiwanese and favoring mainland Chinese or the 228 Massacre. Likewise, the KMT proved less careful in managing Taiwanese natural resources than the Japanese, wantonly felling forests.

The idealization of past Japanese colonialism may not be as strong in Taiwan versus the idealization of British colonialism in Hong Kong, as those who directly remember the Japanese colonial period in Taiwan, which ended in 1945, are fewer and fewer. It is of note that in both contexts, an idealized colonial past is upheld against the threat of Chinese domination, seen as the present form of colonialism.

What Now, After the Sunflower Movement and Umbrella Movement?

OVER ONE YEAR after the Sunflower Movement and the Umbrella Movement, though there has been much criticism from within Taiwan and Hong Kong concerning how effective both movements actually were from former movement participants, the wide-ranging impact of both movements is not to be underestimated. Despite constantly offering performative rhetoric which would claim the contrary, Beijing, which is certainly not stupid, not doubt realizes that future attempts to consolidate what it views as its peripheries will face widespread resistance. If it has come in with a sledgehammer so far where an approach with greater finesse would probably be more successful, we shall see as to whether Beijing learns.

Even as it is a question in Taiwan and Hong Kong as to what future steps will be to counteract the encroachment of Chinese domination, it, too, has become a question for Beijing exactly it is to win over the hearts and minds of Taiwanese and residents of Hong Kong if it is to consolidate its so-called internal problems. The Ministry of Education occupation, with the entrance of high school students in activist politics after last year’s Sunflower Movement was the entrance of college students into politics, is the most striking proof to date that resistance from Taiwan’s young will not cease.

Yellow umbrellas being held in the air in solidarity with Hong Kong during a Tiananmen Square commemoration event which was held in June in Taipei. Photo credit: Brian Hioe

Yellow umbrellas being held in the air in solidarity with Hong Kong during a Tiananmen Square commemoration event which was held in June in Taipei. Photo credit: Brian Hioe

Nevertheless, what remains is whether any “United Front” from groups in Taiwan and Hong Kong who have a shared interest in resisting encroachment by Beijing as well as the respective pro-Beijing politics put in by their respective governments can come together. And if Hong Kong and Taiwan are to have a future, this may be what is needed most precisely in the present. One year after the Umbrella Movement, we may in this sense be asking the same question as before about permanent solutions for the issues it was concerned with.