by Brian Hioe

語言:

English

Photo Credit: 太陽,不遠 Sunflower Occupation

Film Notes is a bimonthly column about Asian film by Freda Nada. This week, however, Brian Hioe writes in about 太陽,不遠 Sunflower Occupation, the documentary produced by the Taipei Documentary Filmmakers’ Union about the Sunflower Movement.

WITH SOCIAL movements, it seems that once recognition of a movement’s historical significance sets in, so, too, does the impulse to document the movement for posterity. It is from this impulse that the documentary film about the Sunflower Movement, 太陽,不遠 Sunflower Occupation (“The Sun is Not Far”) came into being, produced by the Taipei Documentary Filmmakers’ Union.

This documentary impulse is present in current efforts to produce documentaries about the Hong Kong Umbrella Movement in its aftermath and that there was more than one documentary produced about the Sunflower Movement, including a number of individuals actively collecting film during the Sunflower Movement with an eye to produce films. But 太陽,不遠 Sunflower Occupation has been taken up as something of the flagship documentary of the movement. The world of Taiwanese film and television production has, after all, always been quite close to the world of Taiwanese activism, for example, in the weekly anti-nuclear “5-6 Movement” demonstration organized by a group of film directors for close to two years, led by well-known New Wave director and anti-nuclear activist Ko I-Chen.

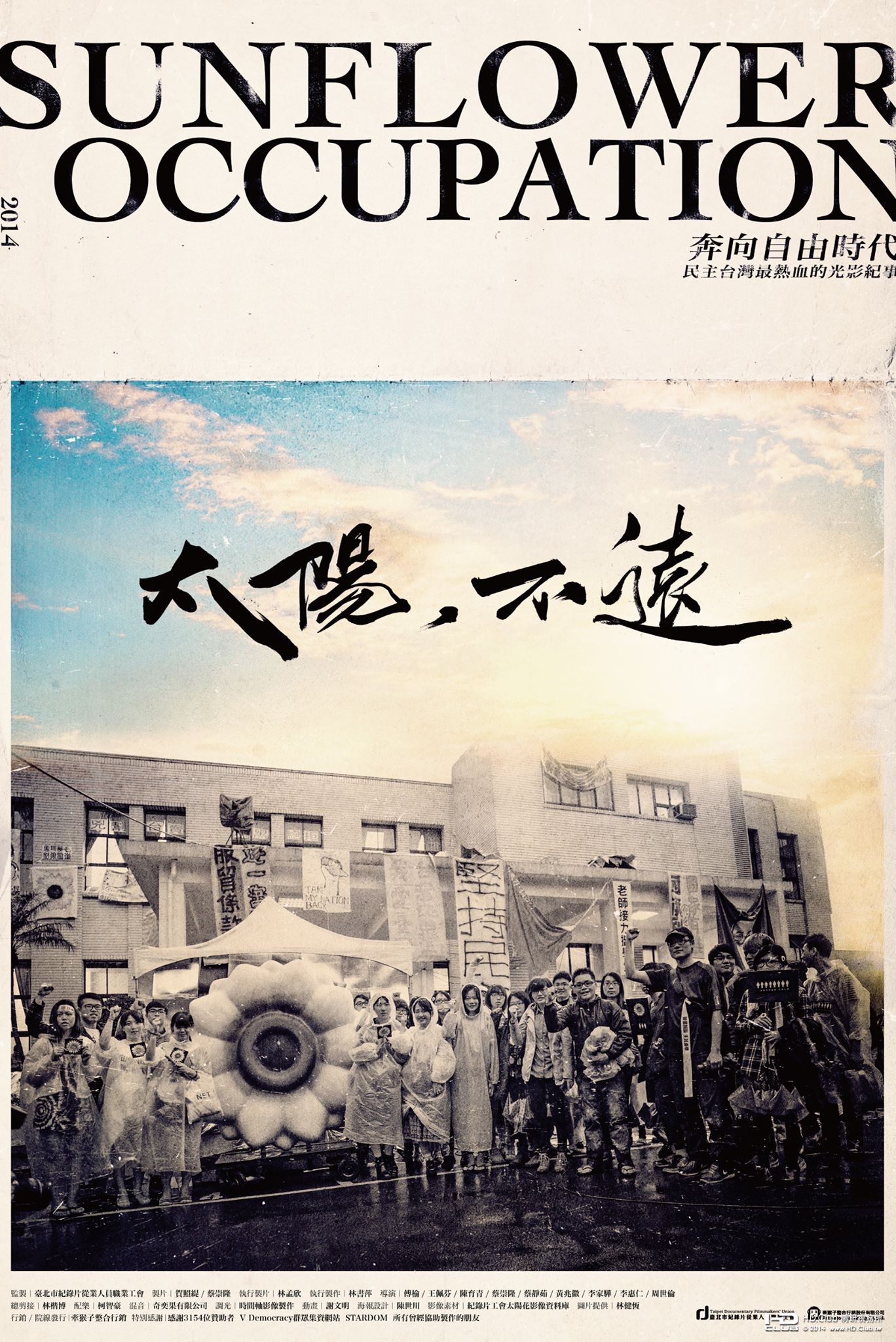

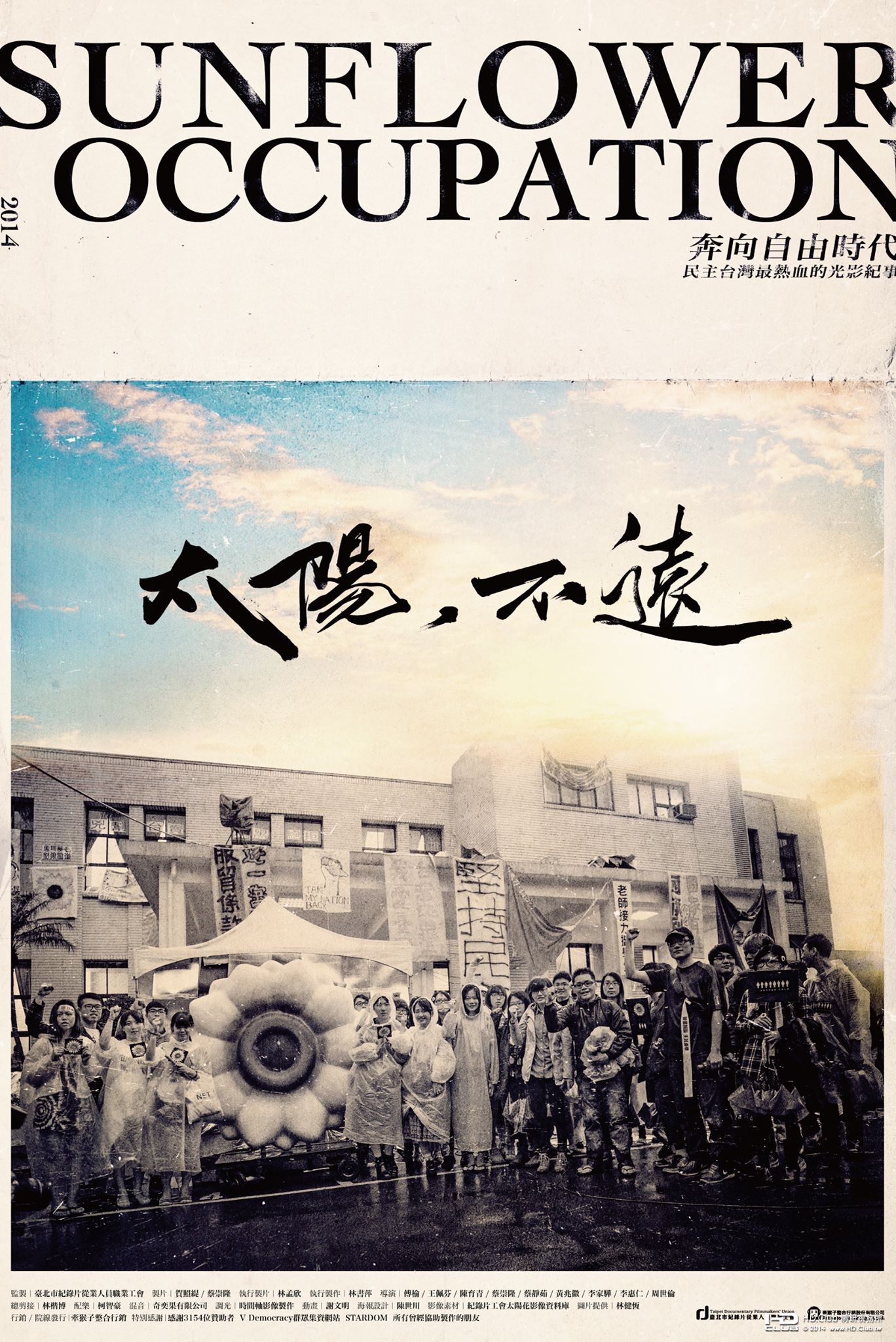

Film poster for 太陽,不遠 Sunflower Occupation. Photo credit: 太陽,不遠 Sunflower Occupation

Film poster for 太陽,不遠 Sunflower Occupation. Photo credit: 太陽,不遠 Sunflower Occupation

It is as such that directors and filmmakers were among those filming the Sunflower Movement and were allowed insider access to crucial events occurring inside the Legislative Yuan. That such a film was able to be produced in the half year after the Sunflower Movement reflects something about the particularities of Taiwanese activism where the intersection of art and politics is concerned. If it were this act of providence that allowed for the film to come into being, it is to our luck as viewers that the film allows to us to look back into the internal dynamics of Sunflower Movement as individuals who were watching afar during the course of the movement, or as participants in the Sunflower Movement itself reflecting on what was recently lived experience.

Yet with a documentary that becomes emblematic of the movement as a whole, the critical tension which is at hand is to what degree to keep to a linear narrative and what extent to take artistic liberties in stylizing the film as something that goes beyond just a retelling of the movement. Where the film covers fairly recent events, 太陽,不遠 Sunflower Occupation choses the latter path, in expectation that most viewers are familiar with the chronological events of the Sunflower Movement. But ultimately, the film is far from a success because it is unable to resolve this tension.

Screening of 太陽,不遠 Sunflower Occupation on March 23rd. Photo credit: 太陽,不遠 Sunflower Occupation

Screening of 太陽,不遠 Sunflower Occupation on March 23rd. Photo credit: 太陽,不遠 Sunflower Occupation

The film begins by quickly going through the chronology of the movement, largely with a focus on student leader Chen Wei-Ting, who is a frequent interview subject during this first part of the film. The film then cycles back and attempts to look back upon different incidents, participant demographics, internal tensions, and individual stories within the movement. But after wrapping up its brief, linear retelling of the Sunflower Movement, the problem is that there is no clear logic behind how the film unfolds from there. Its attempts to zoom in on different elements of the Sunflower Movement that a linear retelling of the Sunflower Movement would have missed are poorly organized, with it being unclear how these elements are supposed to relate to each other except as amorphously encompassed within the Sunflower Movement.

To be sure, the topics of each segment are interesting, and certainly topics that a documentary about the Sunflower Movement need concern itself with. Segments focus in on topics as the personal story of Legislative Yuan occupier Pan-Yi, the Executive Yuan occupation incident of 324, backlash against the central leadership of Lin Fei-Fan, Chen Wei-Ting, and Huang Kuo-Chang, the participation of Mainlander Taiwanese within the movement, and more.

Indeed, if the film is meant to not merely repeat the narrative of the heroism of Lin Fei-Fan and Chen Wei-Ting and the idealistic young students they led during the movement, it would be necessary to speak of dissent against Lin Fei-Fan and Chen Wei-Ting during the movement. This was largely the narrative propagated by members of the media that were supportive of the movement and clung to by the elements of the public which were supportive of the movement but largely unaware of its internal dynamics. And it is to the film’s credit that it attempts to do so, if where the film also heavily features interview with Chen Wei-Ting and footage of student leaders, it conducts such interviews in order to show all angles of the movement in a fair and balanced manner. The events of the Sunflower Movement being very recent, seeing as that if it had not made any moves in that direction, the film would have likely been criticized by activists.

Still from film. Photo credit: 太陽,不遠 Sunflower Occupation

Still from film. Photo credit: 太陽,不遠 Sunflower Occupation

In covering the attempted Executive Yuan occupation that took place on the night of March 23rd into the morning hours of March 24th, “324”, the film takes the position that police violence was unjustified, brutal, and uncalled for. That there was, in fact, a vicious public response against would-be-occupiers for violating public order is glossed over where distance has smoothed over such tensions and 324 has become the story of students suffering police brutality rather than one of student hooliganism and disruption of public order. Historical footage comparing 324 to the 520 incident of 1988 and use of police force in Hong Kong in 2005 are, however, used effectively in this segment. But this is, in fact, one of the weaker segments of the film where the segment is marked by some odd attempts at artistic stylization that do not succeed. One has some sense of the ironic juxtaposition that was aimed for during a montage of children playing in water parks side by side with students being fired upon by water cannons, but the effect is a failure. Similarly, one is also not sure what was being aimed at in a segment showing a student dramatization of the events of 324 as a student play, as juxtaposed with the actual events themselves—the effect comes off as tawdry.

In an attempt to zoom in on the ground level of the movement that the film attempts to cover the story of Pan-Yi, an individual who was present in the Legislative Yuan occupation who was not especially famous. This was likely included within the movie in order to humanize the movement, or personalize it, so that the Sunflower Movement would not just become the story of media celebrities Lin Fei-Fan and Chen Wei-Ting. But while this intent is admirable, this is done clumsily, where the segment featuring Pan-Yi is short, not especially well fleshed out, and terminates without any clear sense for the audience as to how this segment relates to the more dramatic events of the Sunflower Movement which more strongly feature in other parts of the film. Pan-Yi’s story is introduced into the film abruptly, with little context as for the sudden shift in focus. And by the time the segment is over, one still does not have a fully developed sense of what the segment was meant to add to the film thematically.

In its turning towards a consideration of the lesser heard voices of the Sunflower Movement, a segment of the film also focuses upon descendants of Waishengren, Mainlander Taiwanese, who participated in the Sunflower Movement despite having parents who might be in support of the KMT government or have pro-unification stances concerning China. Though it was a stroke of brilliance to include this in the film, one can suggest that filmmakers might have extended their examination of lesser heard voices in the movement in also speaking to Hakka or Indigenous participants, who, frankly speaking, would not have been very difficult to find as interview subjects. But as with the segment featuring Pan-Yi, it becomes largely opaque as to why this segment is featured within the film and how these questions of identity relate to the macro-level events of the Sunflower Movement—especially when this segment occurs so late in the film, near its end, and is inserted into the film without clear explanation. If questions of cultural identity were so central to the Sunflower Movement to begin with, would it not have made more sense to foreground this earlier in the film, as one of the factors of the switch in cultural identification among Taiwan’s young which led up to and were crucial to the Sunflower Movement? That would have made for a more coherent overall framework for the film’s development.

This is largely the problem of the film’s attempts to zoom in on the neglected elements and voices of the Sunflower Movement when there is no clear organization to how to do this, just the sense that the film needs to include something more than just a linear, triumphalist retelling of the Sunflower Movement. It reflects the maturity of the film that it comes to this awareness, but it might have made more sense to organize these disparate segments in a more coherent manner, for example, by proceeding from micro to macro in a manner to illustrate how the dramatic, macro-level events that were featured heavily in the news were constructed out of individual, personal stories on the micro-level, rather than begin with macro-level events in a brief linear retelling of the Sunflower Movement then turning back to cover micro-level events in a manner which did not make clear what the relation between the two was. Arguably, the film might, in fact, have just worked better as a progressive retelling of the Sunflower Movement, if it had been able to fully integrate its thematic material into a linear narrative.

But it may be that the film’s unevenness also reflects the unevenness of the source content of the film—and the film’s uniqueness. The film was compiled out of footage taken by a number of participants in the Sunflower Movement, at all levels of the movement, then put together by a group of directors making the film, in some way, a “crowdsourced” film. This includes, as was heavily advertised in publicity materials for the documentary, footage taken by the aerial drones which were often seen flying around the Legislative Yuan encampment during the Sunflower Movement and apparently owned by participant demonstrators.

Where the film sometimes seems all over the place with the lack of order in footage included, one gets the sense that involved directors were uneasy about cutting footage at risk of not being totally inclusive, where more decisive cutting and a firmer directorial hand would have led to a tighter narrative for the film. Too many cooks spoil the broth, maybe. Yet if the Sunflower Movement in what was sometimes a messy movement, offered a utopian promise of popular democracy for all Taiwanese, perhaps 太陽,不遠 Sunflower Occupation, too, gestures in its very unevenness of constitution towards a set of utopian possibilities for progressive politics going forward after the Sunflower Movement.