Hong Kong’s Struggle Against Political and Economic Reality

by Brian Hioe

語言:

English

DOES THE POSSIBILITY exist for Hong Kong to attain democracy? This question has yet to be settled. In the face of China’s refusal to allow non-vetted candidates to run for Hong Kong’s Chief Executive, the highest political position in the Hong Kong government, the stage is set for Occupy Central to once again seize control of Hong Kong’s Central district, the city’s financial and economic heart.

Occupy Central leaders have vowed an occupation of ten-thousand strong. An Occupy Central occupation in the near future would follow in the wake of a unofficial political referendum which saw close to 800,000 participants and a July 1st rally which Hong Kong University estimated drew 172,000. But Occupy Central has met with opposition. On August 17th, pro-Beijing protestors rallied against Occupy Central’s planned seizure of Central, drawing 88,000 according to a crowd estimate also by Hong Kong University. Pro-Beijing organizers likewise held their own political referendum, which they claimed drew 1.3 million votes, although there are allegations of exaggerated numbers for this referendum.

A more pressing threat to Occupy Central activists and protestors may not come from counter-protest, but from forceful suppression. Four thousand police were deployed for the July 1st Occupy Central protest. It is hard to not to think that more police will be deployed in preparation for a planned mass sit-in; training exercises in preparation for such mass protest have been conducted since late June.

Forebodingly, in an interview with Radio Television Hong Kong, Chen Zou’er, the former deputy director of the Chinese State Council’s Hong Kong and Macau Affairs Office, stated that “blood will be shed” if Occupy Central goes forward with their planned occupation of Central. When asked if the People’s Liberation Army would intervene, Chen did not respond directly, but said that Hong Kong police would address the situation.

Indeed, without further escalation of an extreme magnitude, the situation does not look as though Beijing would be willing to use military force to resolve a possible crisis precipitated by Occupy Central, but the threat of violence used against Occupy Central protestors by the Hong Kong police remains on the table.

It is not clear what day Occupy Central’s seizure of Central will take place, except that it would not take place this past Sunday, as details have been kept under wraps by organizers. Nevertheless, it looks like Hong Kong is headed for a showdown these days. In the backdrop, the fundamental question remains: Is democracy attainable for Hong Kong?

The Impossibility of Democracy in Hong Kong?

DEMOCRACY AS IT EXISTS in Hong Kong is a legacy of British colonial rule. Few Hong Kongers would claim otherwise. Under the Patten administration of Hong Kong from 1992 to 1997, the final British colonial administration of Hong Kong before its handover to Chinese control, reform measures were introduced into the electoral system in 1994 that provided for the broadening of Hong Kong’s electoral base.

These reforms were opposed by and then later repealed by the CCP once the handover of authority took place. Yet the 1994 reforms provided for the so-called “promise of democracy” by which Hong Kongers could legitimately demand of the CCP that they were, in some sense, violating the social contract between Hong Kongers and the Hong Kong government in refusing to condone democratic elections—although such claims were always necessarily couched within the framework of “one country, two systems.”

Indeed, one speculates as to whether planting the seeds of dissent was the intention of the British in introducing democracy in the last ten years of British rule over Hong Kong whereas democratic measures had never been introduced prior to the Pattern administration. Likewise, it is telling that when Occupy Central’s Benny Tai claim on Sunday that with the announcement of the CCP’s policies of governance that “Today is not only the darkest day in the history of Hong Kong’s democratic development,” he simultaneously claimed that “today is also the darkest day of one country, two systems.” What is to be noted is that the demand for democracy is made within the rubric of, once more, “one country, two systems.”

It would appear that the dilemma of Hong Kong as compared to, for instance, Taiwan, is the apparent impossibility of a sovereign Hong Kong. There are, of course, Hong Kong independence activists no doubt active in Occupy Central and related movements. Moreover, like Singapore, Hong Kong’s existence as a territory is defined by its nature as something of a city-state. However, it would appear that for better or worse, Hong Kong is now wedded to China inseparably.

A Struggle Against Economic Reality for Hong Kong?

WHEN ONE PARSES through the vast majority of the arguments, usually coming from pro-business publications, that Taiwan should simply give up its claims of independent sovereignty because Chinese growing economic influence will inevitably cause Taiwan to increasingly fall under China’s sway, one finds something in common between all of them. Namely, their view of economic reality is as absolute objective reality, that is, something like an immutable law of nature. And anything which seeks to oppose this objective, economic law is “irrational”.

For Taiwan to oppose China’s influence over it is therefore unreasonable. It defies something called “reason” or “rationality”. Regardless, when one scrutinizes the roots of this so-called “rationality,” one finds that it is economic reality which is the only reality which can determine what is reasonable or unreasonable for such commentators.

While one more often sees this type of argument made in regards to Taiwan, so, too, for Hong Kong and other countries and territories now facing the threat of expanding China. When the argument is made that China’s growing economy will increasingly demand relations with China that will pave the way for inevitable economic, then political integration, the argument is always made in terms of rationality, reason, and inevitability.

It is true that there is no way out of something we might refer to as global capitalism. China’s growing influence, economic and political, is an unavoidable reality. There are those who simply declare that all those living in East Asia must simply accept the rule of their new Chinese overlords, that this is the only logical outcome, that resistance is futile. Perhaps Hong Kong, Taiwan, and other territories on the fringes of China are merely struggling against inevitable fate. But more often, what those who decry the uselessness of resisting a rising China claim to be “fate” is in fact purely capitalist reality, in which resistance to the decrees of economic logic is irrational and economic logic is the sole determinant of political judgment.

SOME HAVE SOUGHT to emphasize the apparent distinction between the present “Occupy Central with Love and Peace” and the previous “Occupy Central” occupation that lasted from 2011 to 2012 and was more directly an offshoot of the global Occupy movement that began with Occupy Wall Street in New York. Still others have emphasized that the original Occupy Central was much more about Hong Kong’s sovereignty vis-a-vis China to begin with, rather than addressing the issue of economic inequality that other “Occupies” across the world sought to address.

Returning to the heart of the matter, why is it that Occupy Central with Love and Peace seeks to occupy the Central business district, rather than a government building or something of that sort? This planned tactic has been what has led to some measure of opposition from the populace at large—that an occupation of Central will be disruptive of people’s everyday lives, given the importance of Central to many people’s work.

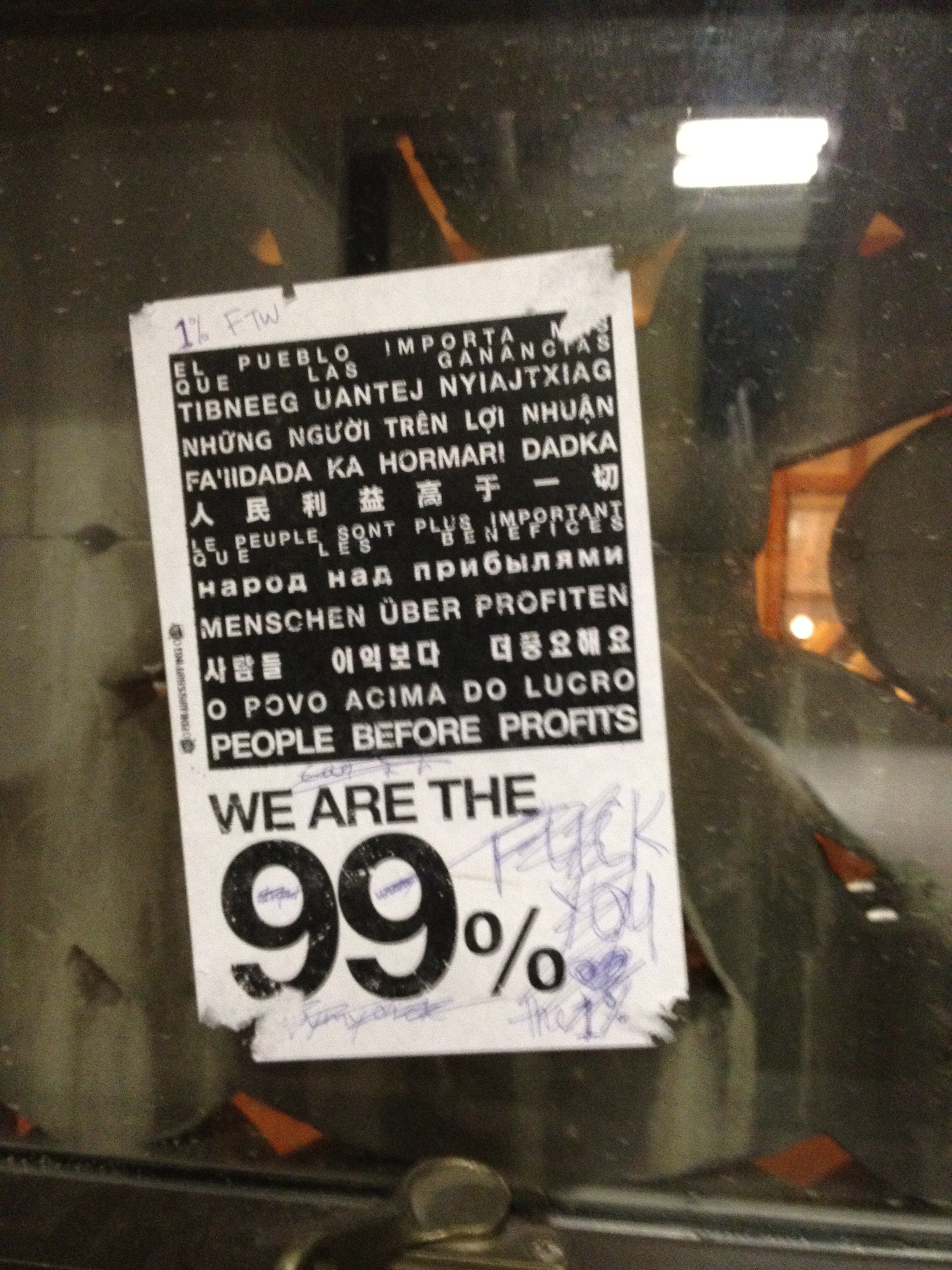

Occupy Wall Street poster, Fall 2011. Photo credit: Brian Hioe

Occupy Wall Street poster, Fall 2011. Photo credit: Brian Hioe

The present author, not having interior access to the discussions on means and ends, tactics and strategies being had in Hong Kong, cannot speak to how Occupy Central participants view the planned occupation of Central themselves. Very likely, on the level of practical logistics, it has to do with the precedent of the 2011 to 2012 Occupy Central, and that there are few other spaces which 10,000 participants could publicly occupy in Hong Kong in order that they might seize something vital to the city and refuse to let go until their demands have been met.

Nonetheless, it seems somewhat evocative that this is the source of controversy over Occupy Central. When it came to the Sunflower Movement last March in Taiwan or Occupy Wall Street in 2011, too, a lot of those who protested against both movements were less concerned with the issues at hand, then with how it disrupted their everyday lives. Yet what was precisely at stake was the larger forces, economic, international, and political, which shape people’s everyday, quotidian lives in the background.

Perhaps a good deal of what is at stake with social movements are precisely the everyday lives of people, but it takes the shape of a struggle against the quotidian. Certainly people whose everyday lives will be inconvenienced by Occupy Central will very likely later have to endure the consequences of stricter controls upon the freedoms they take for granted in their everyday lives.

WHAT HONG KONG, Taiwan, and other territories are facing is the means by which China exerts its political influence upon its surrounding countries and territories through economic means. The occupation of Central regarding Hong Kong’s ability to determine its own governance takes the form of a confrontation with economic reality to the extent that the issue of democracy for Hong Kong is one deeply bound up with the broader panorama of global capitalism and Chinese power in the Asia Pacific region as its influence is made felt through economic influence.

In the Taiwanese context, the rise of the Sunflower Movement regarding the Cross-Strait Services Trade Agreement (CSSTA), a free trade deal between Taiwan and China, brought forth the issue of economic and political power. Opposition to the CSSTA free trade bill on the part of activists belied opposition to the political power of China behind the bill as manifested through the anti-democratic actions of Taiwanese KMT legislators acting as China’s proxies.

The situation in Hong Kong would seem to be similar, with the Hong Kong government serving as China’s proxies and carrying out similarly anti-democratic actions. It is small wonder that one will rather frequently see in the media a picture of an activist from Hong Kong wearing one of the famous “Fuck the Government” t-shirts from Taiwan which are a staple at any protest in Taiwan. The sentiment would seem to equally apply.

The Taiwanese Legislative Yuan occupation on April 4th, 2014. Photo credit: Brian Hioe

The Taiwanese Legislative Yuan occupation on April 4th, 2014. Photo credit: Brian Hioe

However, in comparing Taiwan and Hong Kong, once must note the degree to which the situation in Hong Kong is more wretched. For all the back-and-forth of “cross-strait relations,’ at least Taiwan has a strait separating it from China. Taiwan has a de facto if not pro forma independence which Hong Kong does not have.

To touch on a fresh wound, when one looks at the recent harassment and collapse of independent news sources in Hong Kong, one can observe the very direct exertion of both Chinese economic and political power at hand. With the shutting down of House News, House News was unable to maintain itself because advertisers were afraid to take out advertisements in it for fear of political reprisal. That combined with the political pressure that its founders and staff members were facing led to its decision to shut down. Media tycoon Jimmy Lai, owner of Next Media and Apple Daily, appears now to be facing a similar combination of Chinese economic and political pressure. Once more, while Taiwanese activists are facing down “media monopoly” from China, Taiwan has at least some measure of distance when it comes to such direct means of coercion.

For an occupation to succeed in any form, it needs to take hold of something vital to the forces it is making a demand of and refuse to let go until its demands have been met. So, the logic for seizing Central, which is vital to Hong Kong as a whole. The point would be to force the struggle for Hong Kong’s fate into center stage, whereas another location might allow for Occupy Central to more easily be swept into the everyday realities of people and become just another thing which people know about happening in the background of their lives but don’t pay attention to. Yet given that it is often through economic means that Chinese political power manifests itself, the occupation of the Central business district thereby takes on some measure of symbolic resonance when it comes to this confrontation with economic reality.

In this light, Occupy Central with Love and Peace in 2014 may be a true Occupy, after all. But it faces the same inherent challenges of any occupation-based movement.

Can Hong Kong be the next Taiwan, or Singapore?

THE STRUGGLE OF Occupy Central and of Hong Kongers for democracy will no doubt be a long-term one. Even if the occupation of Central will very probably occur in several weeks and may last as long as or exceed the previous Occupy Central occupation in length, the election of Hong Kong’s Chief Executive is slated for 2017.

Between Hong Kong, Taiwan, China, and America, the future years which will be determining of the course of democracy in Asia seem to be lining up. 2016 will be the next American presidential election, which will determine the future course of America foreign policy towards China, and it will also be the year of the next Taiwanese election—to which extent, future Chinese policy towards Taiwan will be determined by who is victorious. One can only expect the amount of protest in Hong Kong leading up to 2017 to increase, especially as Hong Kong’s current generation of college activists become graduate students or part of the work force, its very young high school student activists become college students and college-based organizers, new high school students become politicized and politically active, and old veteran hands keep at organizing. And 2020 will be the year that China’s military strength is enough to occupy Taiwan.

Scholarism activists in 2012, Joshua Wong in the center. Photo credit: VOA Chinese

Scholarism activists in 2012, Joshua Wong in the center. Photo credit: VOA Chinese

Yet to return to the question with which we began, what exactly are the possibilities for Hong Kong to achieve democracy? Hong Kong, having been wedded to the British empire for so long, is now bound to China—or, dare we say, the Chinese empire?

Despite that Taiwanese and Hong Kongers often perceive an affinity between their respective situations, the Taiwanese model is very probably not one that Hong Kong can achieve. Geography and political history renders this impossible.

A perfect ideal of “One country, two systems” probably can never be realized, since the freer Hong Kong will always have the less-free mainland China looming over it as a possible future, and a freer Hong Kong would always pose some measure of danger to tight CCP control over mainland China because it would pose a vision of possibility of a freer society for the rest of China— whether this possibility is in fact mostly imagined mostly in the minds of the CCP or not. Nevertheless, because self-determination for Hong Kong seems impossible, Hong Kong’s situation would seem to be inherently wretched and without possibility of resolution.

There is, however, one speculative model which Hong Kong could follow—that of Singapore. Singapore, after all, is able to maintain itself as a city which operates as a nation. Hong Kong could attempt to aspire to the same; however, Singapore’s independence from Malaysia was attained not through any sort of independence movement but through the unique circumstance of Singapore being driven out of Malaysia without necessarily desiring independence itself.

Could Hong Kong replicate this set of circumstances? The particularities of the situation are not the same. Singapore’s expulsion from Malaysia in 1965, though a product of Malay-Chinese ethnic tensions endemic to the region, also had causes in Malaysia’s instability at the time period given that Malaysia had only been established as a federation of preexisting territories in 1963 following a period of British rule, of which Singapore was one. Furthermore, Singapore had actually pursued entrance into Malaysia before this was later revoked with its expulsion.

Though Hong Kong never had anything like the luxury of being able to determine to seek entrance or exit to which power held territorial sovereignty over it, Hong Kong has had an independent identity from China for some time as yet another legacy of British colonial rule. However, China will be loath to let go of Hong Kong, given its political, economic, and cultural importance. If Hong Kong is to aim for a scenario where China finds itself wanting to be rid of Hong Kong, the point would be for Hong Kong to make itself as unbearable to China as possible through constant protest and other measures and to generally conduct itself with a flagrantly defiant sense of independence in its affairs.

The lesson illustrated by Occupy Wall Street is that occupations often do not succeed, even when they have cleared the initial hurdle of not being driven out by the police from the onset, and forming a long-term encampment. Without a planned endgame, occupations more often terminate through bleed-off from attrition or being driven out by police at some point after public apathy has set in. And no occupation can last indefinitely.

It does not do to speculate as to how Occupy Central with Love and Peace will end after it has not yet even begun, however, it bears pointing out that the odds are against Occupy Central. Yet Occupy Central with Love and Peace is already the second coming of Occupy Central. If the project of achieving democracy in Hong Kong to stand anything like a hope of succeeding, Hong Kong may require many more Occupy Centrals in the years leading up to 2017.

And so the eyes of those on the fringes of China are set on Hong Kong these days. To the extent that what happens in Hong Kong will no doubt influence future Chinese policy towards countries and territories on its perimeter, including Taiwan, Macau, and others. The struggle of Hong Kong at present will affect more than just Hong Kong itself—and Hong Kong activists are thereby advised to keep in mind the international character of their struggle.

Though much has been touted about ties between Taiwanese activists and Hong Kong activists, or the sympathy Taiwanese feel for Hong Kong and vice-versa, such ties remain to be transformed into something substantial. There have been cases of a few devoted activists going over from Taiwan to Hong Kong to share skills or observe the course of events, but this is not enough. Intimate strategizing on both sides has yet to happen. But in the months and years to come, perhaps such networks may develop. Certainly, they will be of vital necessity if anything like opposition to growing Chinese power in the Asia Pacific region is to be possible. Can democracy in Hong Kong be achieved? The jury is still out. But democracy in Asia itself is at stake here.