by Brian Hioe

語言:

English

THE SPECTER OF TAIWANESE POLITICS is everywhere in the artwork of Dean I-Mei. While, certainly, the artist himself poses his recent exhibition in light of a search for personal identity in the title “Wanted Dean I-Mei,” his search for individual identity is one deeply bound up with Taiwan’s state of unbelonging in the world.

An artist working heavily in mixed media, Dean I-Mei graduated from Chinese Culture University in Taiwan in 1977, subsequently undertook graduate studies at the Pratt Institute in New York from 1983 to 1985, and returned to Taiwan only in 1993. This would appear to be the predominant theme of his work—the search for identity in the midst of displacement. Through all phases of the work, Dean would seem to be searching for “identity,” whether as “Chinese” or “Taiwanese,” and with a prominent focus on Taiwan’s place in the world after his return to Taiwan.

Perhaps as an entry point, we might focus upon history as a lens into what Dean poses through his work. With the increasing preoccupation with Taiwanese identity as bound up with the tangles of Taiwanese history in his work through the years, Dean focuses upon three periods: the “recent” history of the split between Taiwan and China following World War II, the ambiguous history of the Republican period which is appropriated by the KMT in Taiwan or the CCP in China, and the late Qing/early Republican period in which the “feudal” China of antiquity came into contact with western modernity and subsequently was unable to maintain itself.

DEAN’S EARLIER ART dating from his formative period of studying in New York strikes as largely derivative, if not presaging the thematics of what is to come later. Dean’s influences are for the most part postmodern in influence, then, ranging from Jaspers to Warhol to Duchamp and other canonical names. He covers the usual themes of an artist living in New York in the late 70s and early 80s: the AIDS crisis, sexuality writ large, America’s ambiguous place in world affairs in the aftermath of Vietnam, consumerist capitalism, etc. Yet one can perceive in this early work, the early inklings of his attempt to work out something bridging the gap between western modernity and traditional Chinese culture. For example, one of Dean’s sculptures is a version of the iconic Love sculpture combined with the Chinese character for love. Another example is a readymade of traditional Chinese clothing with Malevich’s archmodernist black and red square stamped upon it.

“Love.” Photo credit: Brian Hioe

“Love.” Photo credit: Brian Hioe

Dean, originating as a “Mainlander” Taiwanese of Shanghainese descent, was already caught in the ambiguous gap between Taiwan and China. It appears that this led him to an interest in the mixing of different ethnic Chinese in Chinatowns in America while living in New York. However, one can locate the shift in his work antecedent to the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre, after the events of which Dean travelled to China to see what was going on there firsthand. Dean would subsequently produce a series of engravings called Impressions, reflecting the imprint of tank treads in his memory in regards to the lingering perceptions Tiananmen left upon him.

“Impressions.” Photo credit: Brian Hioe

“Impressions.” Photo credit: Brian Hioe

Nevertheless, it would be from after this that Dean’s mature political artwork took shape. Dean’s political artwork would highlight the strangely symmetrical nature of the CCP and KMT.

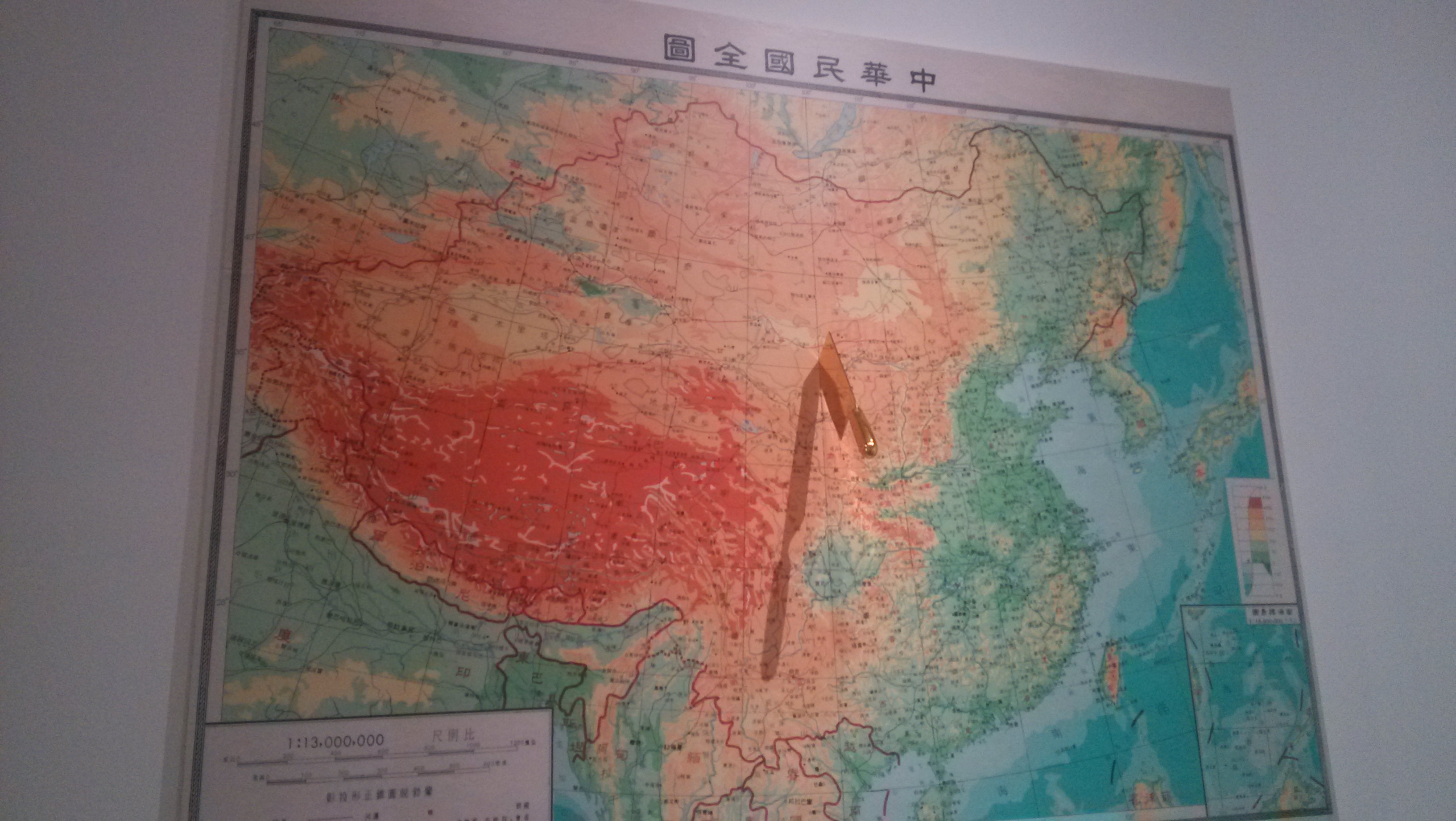

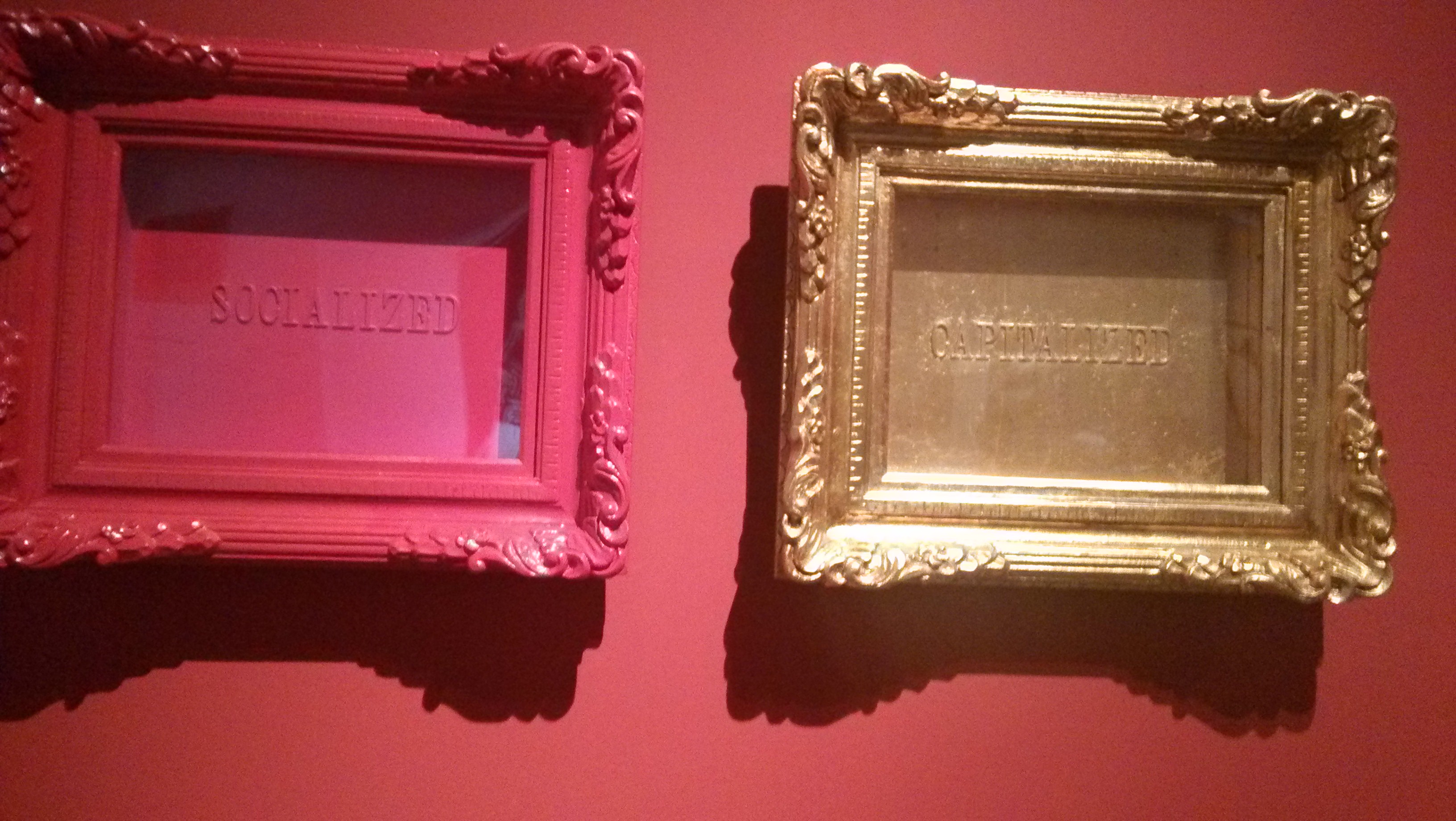

Examples include a series of framed works, “Swinging Memorandum,” works highlighting the juxtaposition between the CCP and KMT, with a red picture frame blazoned with “Socialized” on one side and “Capitalized” in a gold frame on another side in one iteration, and “Communized” in red and “Chinized” in gold in another iteration. An additional standout work in this vein is the 2003 “Political Alchemy,” which focuses upon the contortions of history that Kinmen Island went through as a site of military conflict between the KMT and CCP from the 1950s to the 1970s, but in contemporary times a site for the rapprochement of the KMT and CCP. This relationship is symbolized through the popularity of knives made from the metal from old shells in contemporary times and one of these knives stabbed suggestively into a map of China.

“Political Alchemy.” Photo credit: Brian Hioe

“Political Alchemy.” Photo credit: Brian Hioe

After Tiananmen it seems that Dean turned towards considering Taiwan and China from the specifically the standpoint of Taiwan rather the broader one of Chinese culture writ large. One might note that in the aforementioned juxtaposition between “Communized” and “Chinized” in “Swinging Memorandum” the gold surface in the frame of “Chinized” is reflective, allowing the viewer to see himself as reflected through the Taiwanese experience by way of the artwork, embodying Dean’s experience in refracting the Taiwanese, rather than Chinese experience. Still, does Dean point towards broader historical parallel between Taiwan and China.

“Swinging Memorandum.” Photo credit: Brian Hioe

“Swinging Memorandum.” Photo credit: Brian Hioe

Dean’s most famous work focusing on Taiwan’s position in the world, then, would seem to be “I-Den-Tity,” a piece which marks off Taiwan’s number of allied nations in the world whenever displayed through a display of ceremonial plates. Since it was first staged in 1994, Taiwan’s number of allies has dropped from 29 to 22 (and now 21, with the loss of Canadian acknowledgment). A work following the same vein is “Give Me Hugs,” which appears to do the same, except with pillows, and “Taiwan Loves Japan,” focusing specifically upon Taiwan and Japan’s relationship.

Whereas Dean’s contemplation of Taiwanese identity is derived from a Mainlander Taiwanese perspective, Dean also turns towards criticizing not only the KMT, but the DPP and nativist Taiwanese national identity in some sense. His large-scale “Outside Field Battle” series contemplates the visceral but also fantastical possibility of CCP war upon Taiwan in response to Chen Shui-bian’s declaration that war between Taiwan and China would not be a civil war, but war with another nation.

DEAN’S ARTWORK ENGAGES with the broader consideration of modernity whereby Dean roots the KMT and the CCP alike in a shared structural, historical condition. This would be the coming of western modernity and the development of capitalism. “Confucius’ Confusion,” for example, sets the CCP’s denunciation of Confucian thought through upholding the May 4th Movement’s attempt to extirpate Confucianism in stark comparison with the KMT’s affirmation of Confucian thought in response. This conflict of affirmation versus denunciation, of course, thereby “confuses” Confucian itself to the degree that the actual history of China and Chinese culture is not grappled with, just appropriated in various contradictory ways to affirm present reality.

“Confucius’ Confusion.” Photo credit: Brian Hioe

“Confucius’ Confusion.” Photo credit: Brian Hioe

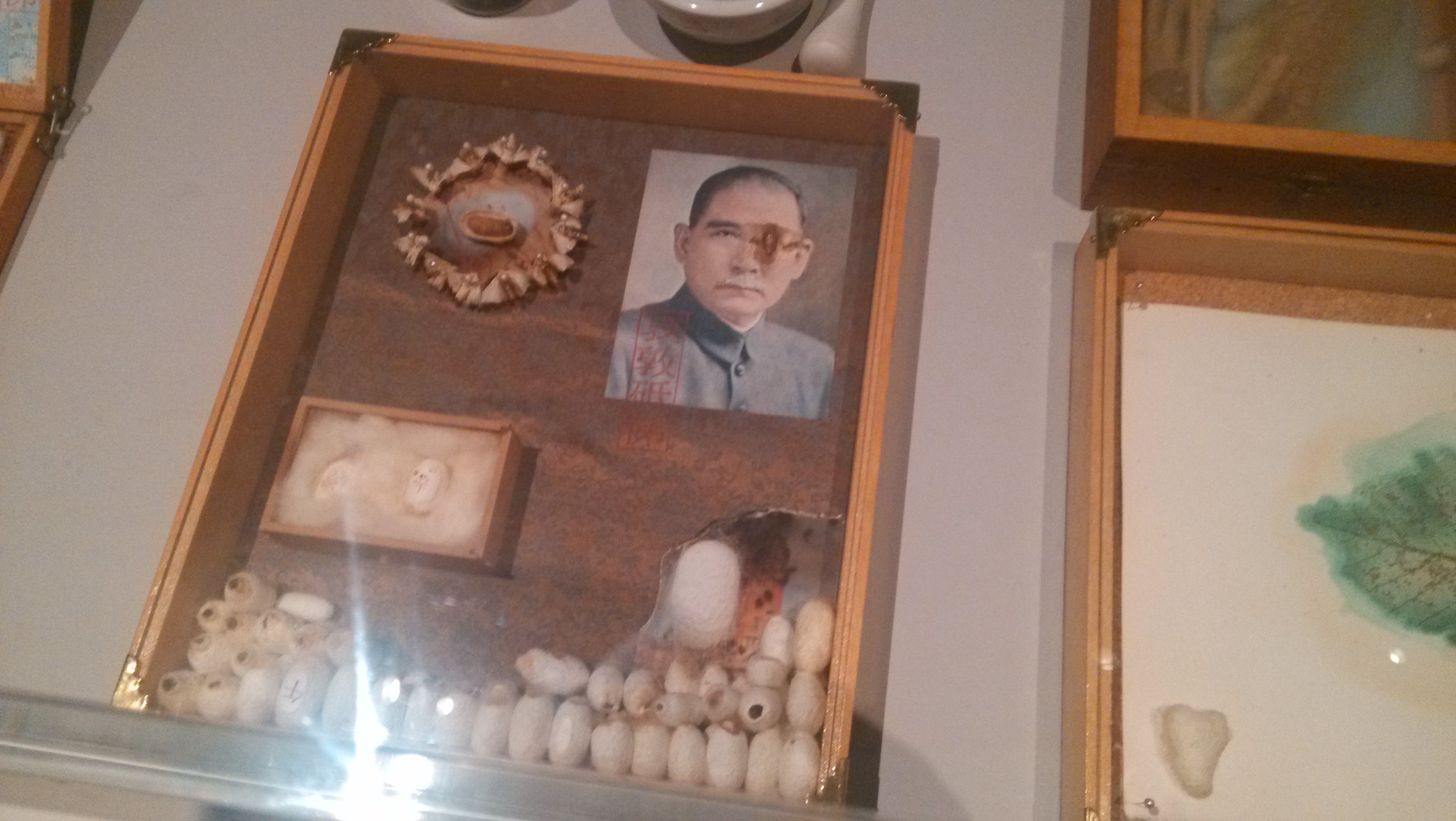

Similarly, “Silk Road-Broche China” jumps back to the history of the silk road, with Dean suggesting that China itself might be something like a silkworm in chrysalis or a silkworm grotesquely torn out of chrysalis. Yet it is ambiguous whether Dean means to suggest that this means that there could have been some form of “alternative modernity” for China or Taiwan nipped in the bud, or that Asian modernity is still in a cocoon-like stage of development.

“Silk Road-Broche China.” Photo credit: Brian Hioe

“Silk Road-Broche China.” Photo credit: Brian Hioe

What both works point to is the degree to which the KMT and CCP offer refracted visions which may represent opposing responses but the way that they are responses to the lingering remnants of the pre-modern. “Confucius’ Confusion” suggests, for instance, that the CCP’s angle on extirpating Confucianism may actually just replace the Confucian worship of the Analects with worship of Mao’s Red Book.

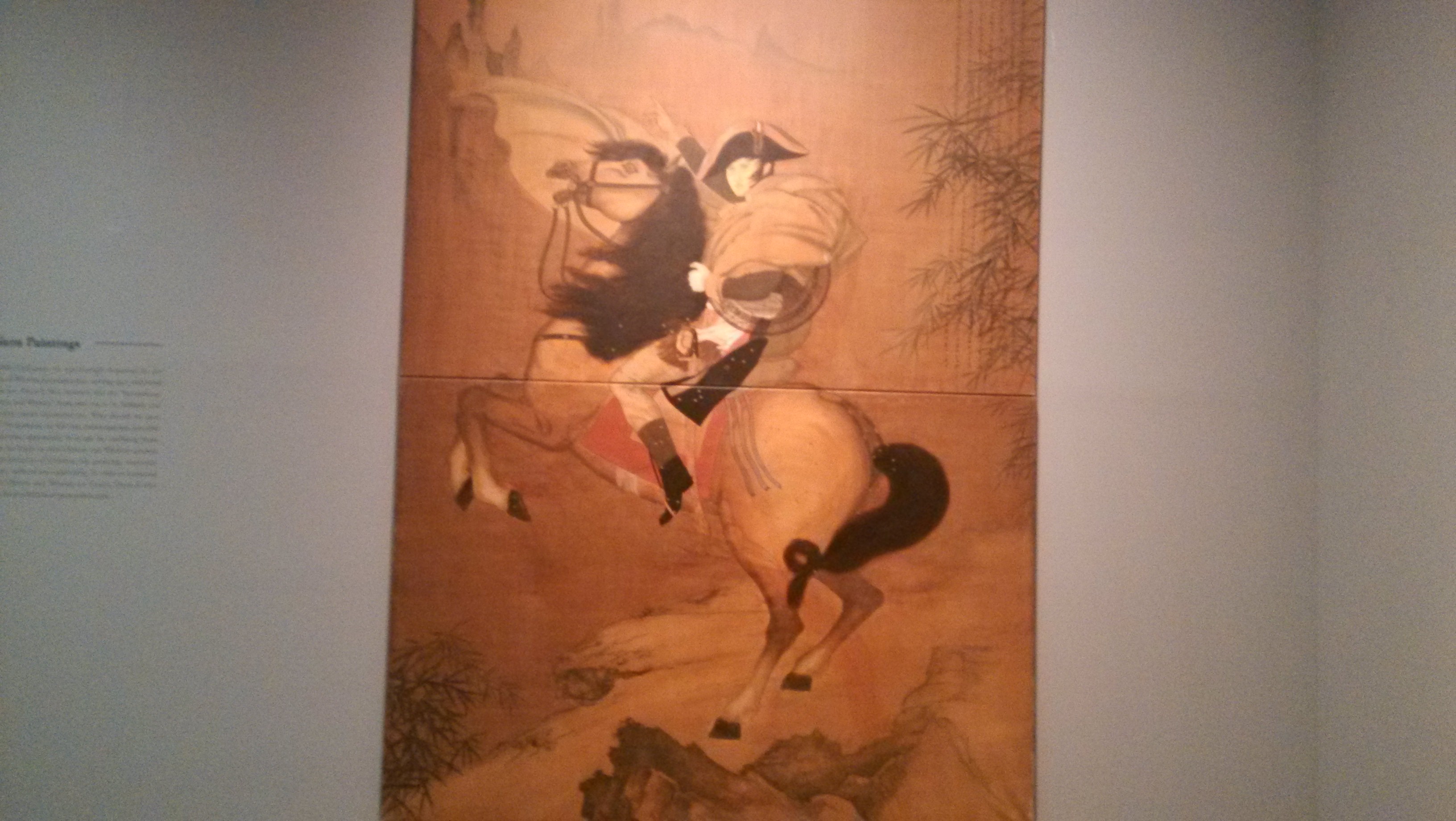

And this is a mature conclusion. But in the sense that so much of postmodern art would seem to seek a happy synthesis of western modernism with some form of older indigenous culture, usually that of the artist’s ancestral origination, Dean’s work does seem to suggest he is seeking a happy synthesis of East and West, but it falls short. His series of paintings attempting to depict western subjects in traditional Chinese ink painting style falls short and only evokes postmodern irony—unless the irony of failure is his intent. Nevertheless, bridging the gap between his late work and his early work, it becomes clear that this has been an ongoing endeavor through his career and that Dean, like so many others, if anybody at all, has not been successful. Dean can only but privilege one side or another and it is in fact the West which ends up being privileged, as Dean cannot help but be derivative of Western, rather than Eastern art. Western portraiture done in ink painting style is still more western portraiture more than traditional Chinese ink painting, after all.

Photo credit: Brian Hioe

Photo credit: Brian Hioe

Such works are, in the end, still fundamentally derivative of western tropes because quite simply, aiming at some sort of older, pre-modern form of indigenous art (i.e., traditional Chinese ink-painting), cannot help but be anachronistic at best or simulacra at worst in the inescapability of the present. Regardless, Dean’s attempt to grapple with this problem is certainly an important one and one that may necessary for future attempts to go beyond what he has achieved—and his achievements are not unimpressive.